The Bank of New Zealand brokered finance of £3 million from the London and Sydney money markets to escalate the New Zealand Wars. With a chronic case of ‘terrible twos’, the BNZ also bankrolled the Colonial Government’s overdraft while war was waged on Māori in the Waikato, the Bay of Plenty, Taranaki and Whanganui.

Dispatch from Ihumātao #003

By Snoopman

Finance to Escalate the ‘Maori Wars’

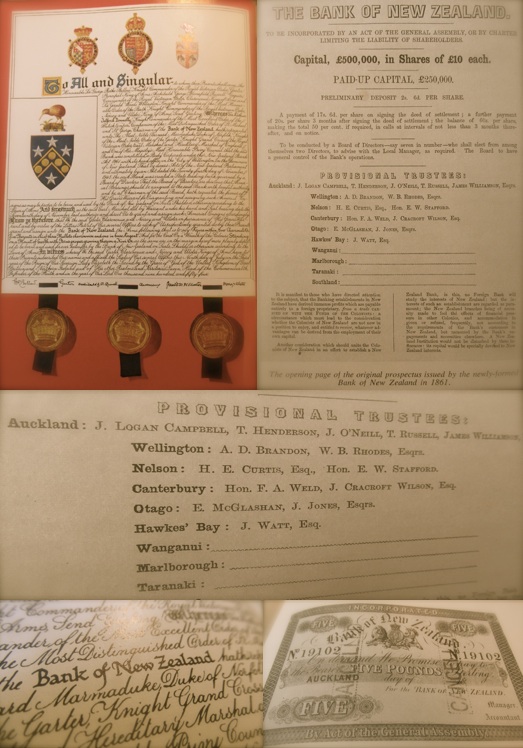

Three weeks after militarist Freemason Bro. George Grey’s ‘homecoming’ for a second term as governor, an ambitious new bank, with initial capital of £500,000 in £10 pound shares, cashed in on colonial parochialism by calling itself the Bank of New Zealand.1

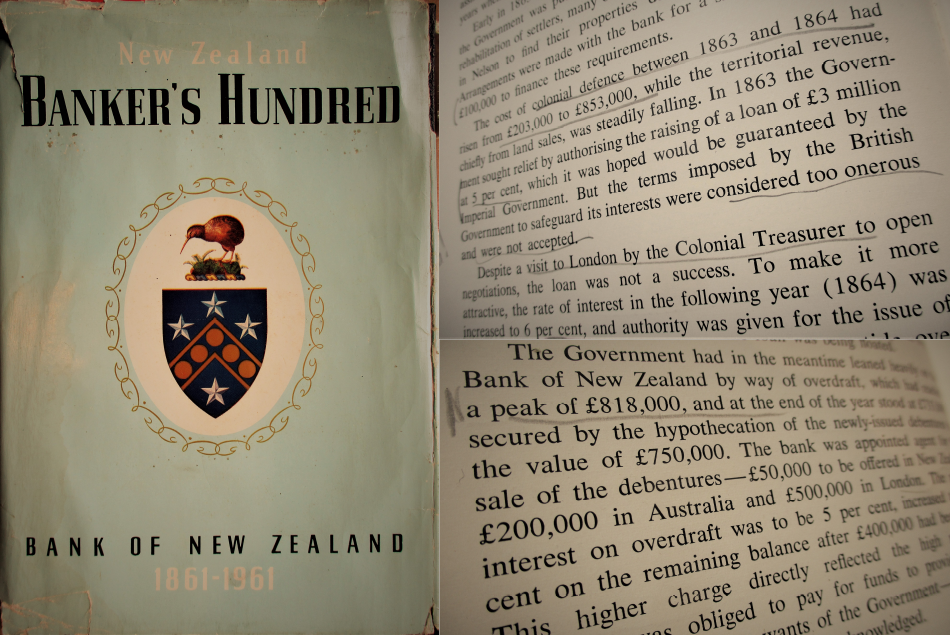

The Bank of New Zealand – which was established by Royal Charter and Colonial Government legislation in 1861 – brokered finance of £3 million from the London and Sydney money markets to escalate the New Zealand Wars, after the Imperial Government’s terms were deemed to onerous and were declined.2

The First Taranaki War of 1860-1861, which had ended inconclusively, was bruising for the egos of the Taranaki settlers and the Colonial Government, whom had expected to inflict a short, sharp shock to defeat ‘the rebellious natives’ with the help of the British Royal Navy and British Army.3 The Taranaki settlers, the Colonial Government and New Zealand Freemasonry had conspired to make the coastal village of Waitara a flashpoint to trigger the Taranaki War – as The Snoopman showed in his exposé essay, “The Masonic New Zealand Wars: Freemasonry as a Secret Mechanism of Imperial Conquest During the ‘Native Troubles’”.4 The settlement of New Plymouth lacked a natural harbour, while 10 miles north, the village at Waitara had a river suitable for a port and fertile fields and gardens belonging to Te Āti Awa iwi – whom were callously targetted with what The Snoopman has termed a wedge of war strategy.

To continue to wage the escalation of the ‘Maori Wars’, the New Zealand Colonial Government needed money. The Bank of New Zealand quickly became the colonial government’s banker. When the initial war bonds and securities to invest in the ‘Maori War’ did not sell at the London and Sydney bond markets as well as the criminal banking cliqué had wished, the Bank of New Zealand doubled down. At the age of ‘terrible two’, the N.Z. Government’s banker supplied a monthly overdraft at 5 to 7 percent ‘interest’. This credit line varied and peaked $818,000 during the Waikato War.

Indeed, the Bank of New Zealand had the edge over older rivals. For one thing, the Bank’s solicitors were Freemason Attorney General Bro. Frederick Whitaker (1812-1891), and the Bank’s primary founder, who happened to be Bro. Whitaker’s law partner, Thomas Russell (1830-1904), of Whitaker and Russell.

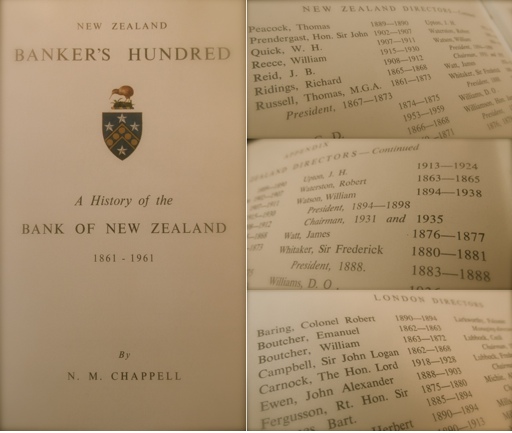

The ‘Limited Circle’ of Russell’s colonial cronies were well-connected Freemason players, as is evident in the roll of the bank’s original directors, investors and trustees. Thomas Russell’s ‘Limited Circle’ included: early investor Governor Bro. George Grey; Bro. Frederick Whitaker; three-times Premier Bro. Edward W. Stafford of Nelson; Wellington based land swindler Bro. William Barnard Rhodes; Bro. C. J. Taylor, Bro. Thomas Henderson, and Bro. A. de Bathe Brandon. The bank’s first president, James Williamson, conducted profitable business for the military commissariat department.5

For his inglorious part, Freemason Bro. Frederick Whitaker – who in addition to being the Bank of New Zealand chief solicitor at the time of the Bank’s founding in 1861 – was also the Colonial Government’s Attorney General. In his role as Attorney General, Bro. Whitaker had a hand in forging the Taranaki Wars of 1860-1863, by misleading the government over their purchase of the highly contested land at Waitara. Bro. Whitaker advised the Colonial Government that the Crown had acquired title properly.6 Whitaker claimed he based this advice on Freemason Brother Donald McLean’s assessment (1820-1877), a wealthy landowner, administrator and negotiator who spoke fluent Māori and was made Chief Purchaser of Native Land in 1853 during Governor Bro. Grey’s first term.7

Like all criminal groups whom are left to remain at-large, the Pākehā settlers who had formed a confederacy to wage war against Taranaki Māori – doubled down to plot an escalation of the ‘Maori Wars’.

With a chronic case of ‘terrible twos’, the Bank of New Zealand also bankrolled the Colonial Government’s overdraft while war was waged on Māori in the Waikato, and then the Bay of Plenty and the Taranaki and Whanganui regions.

Executive Branch of the ‘Limited Circle’

Conspicuously, the BNZ’s primary founder, Thomas Russell, also became the Minister of Colonial Defence (1863-1864) – which placed him in the position to allocate funds for the Waikato War – while Bro. Frederick Whitaker became Premiere of New Zealand.8

By occupying these key political positions prior to and during the Waikato War of 1863-64, the Bank of New Zealand’s primary founder Thomas Russell and his law firm partner, Freemason Bro. Frederick Whitaker, were able to drive the ‘wedge of war’ deeper with three more parliamentary acts. The Suppression of Rebellion Act of 1863 cast Māori as insurrectionists, while the New Zealand Settlement Act ‘legalized’ the establishment of military towns on confiscated land, and the New Zealand Loan Act authorized ‘borrowing’ of three million pounds from the Imperial Government to consolidate this far-flung colony of the British Masonic Empire.

When Thomas Russell became the Minister of Colonial Defence in 1863, Parliament was like an executive branch of the Bank of New Zealand. No less than 28 shareholders and five directors of the Bank of New Zealand were in the Colonial Parliament with the founder.9

The Bank of New Zealand’s centennial book mentions nothing of its first chief solicitor’s culpability in this British Masonic racketeering. In the opening paragraphs of, New Zealand Banker’s Hundred: A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861-1961, author Chappell stated:

“The Auckland of 1861 was conspicuously a colonial outpost of Empire … Problems and anxieties stood plain, not least a growing threat of conflict with the Maoris. But Lord Palmerston [British Prime Minister 1859-1865], half a world away, had declared that British law should be respected in New Zealand, even if it should take 20,000 men to bring about that result.” 10

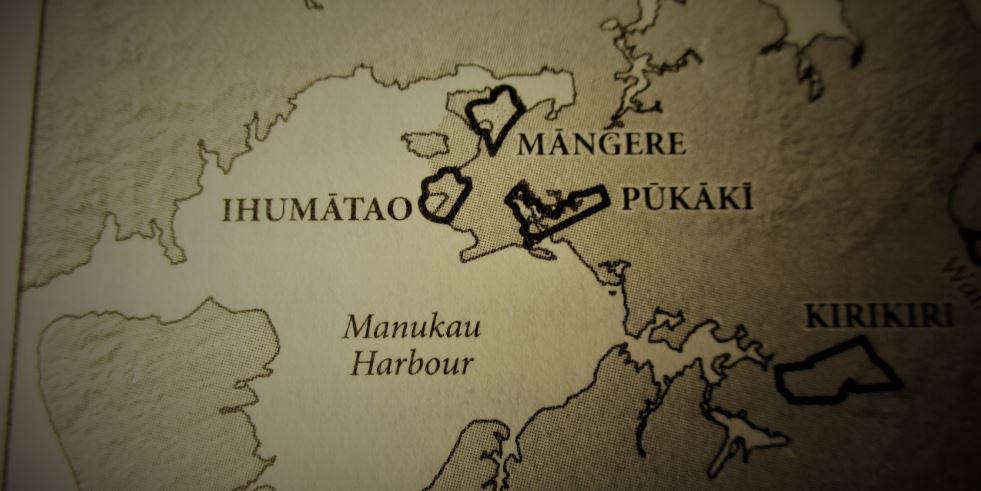

With the finance to prosecute a major war, Freemason Bro. Governor George Grey spent 21 months planning the ‘Maori Wars’ into the Waikato, Taranaki and Bay of Plenty. As David Grant found while researching his book, Bulls, Bears & Elephants: A History of the New Zealand Stock Exchange – Governor Bro. Grey was among the early prominent investors in the Bank of New Zealand. It was Governor Bro. Grey who authorized an ultimatum, dated 9 July 1863, demanding that ‘the Natives’ of Ihumātao – as well as nearby Mangere and Pukaki, and also Te Kirikiri, Patumahoe, Pokeno and Tuakau – submit to the sovereignty, or mana, of Queen Victoria. The proclamation also demanded Māori to hand over their weapons, or they would be force-ably ejected if they did not vacate their lands. In this cruel way, Māori of Ihumātao were evicted.

Once were welcoming ‘Natives’: The Ihumātao Wesleyan Mission Station was established in the mid-to-late 1840s and built with Māori ‘free labour’ – but were evicted in 1863 with the slander that they were in rebellion.

Despite having helped build the Ihumātao Methodist Wesleyan Mission Station in the mid-to-late 1840s, and being appreciated by some of their neighbours as peaceful people whom traded the produce from the walled, volcanic stone fields – the sovereign rights of mana whenua meant little to the Bank of New Zealand’s primary founder, Thomas Russell, who was a Wesleyan lay-preacher. As The Snoopman will show in Dispatch from Ihumātao #004 – The Methodist Connection, some of the confiscated land at Ihumātao was leased to Thomas Russell’s brother-in-law, Henry Vercoe, of the reknowned Methodist Wesleyan settler family – the Vercoes. Moreover, another Wesleyan, Scottish farmer Gavin Struthers Wallace, bought Lots 13 and 14, comprising, 81 acres for £658 when land at Ihumātao was auctioned by the Waste Lands Office on July 17th. Furthermore, Reverend Thomas Buddle – who witnessed the election of King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero at Ihumātao in mid-1857 and wrote the first full report on the development of the Kingitanga – subsequently worked for Whitaker & Russell and eventually became a partner.

‘Limited Circle’ Legacy

Vast swathes of land were confiscated in Māori territories where the Masonic Colonial and Imperial forces made war. In all, 1.3 million confiscated hectares became Masonic territories, and were used as collateral for loans raised to wage war during this period.11 On the fraternally symbolic date of May 13th of 1864, the Bank of New Zealand opened an agency in the garrison town of Ngāruawāhia, the base of the Kingitanga, which had been insultingly renamed Newcastle.

This extension of the bank’s “operations to Ngāruawāhia, the northern gateway to the rich and promising Waikato basin” symbolized another franchise of the bank start-up. Here, at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipa rivers, the Bank of New Zealand’s investors were signaling they were capitalizing on the ‘primitive accumulation’ of land by conquest. The BNZ’s fundraising for the Waikato War was instrumental in forging a new Masonic Territory.12

The smug humour of the Colonial Crony Capitalists, especially those in the inner-circle of the Bank of New Zealand, is cringe-worthy.

Through all of this epic rort, the investors in the Bank of New Zealand received handsome dividends every year right through until 1887, when bank president John Logan Campbell informed shareholders that a dividend would not be paid amid an economic depression. The monetary cost of the war is widely thought to be £3,000,000, which was evidently a “permanent loan”. This description of a permanent loan is given some weight by historian J.B. Condliffe, who stated in his 1927 edition of A Short History of New Zealand that a part of the public debt, a figure of £2 million, is recorded year on year as ‘Maori War debt’, meaning that “two generations of New Zealand taxpayers have therefore paid interest upon the loans raised in the ‘sixties to pay the expenses of the war.”13

In his History of the Bank of New Zealand, author N.M. Chappell brazenly sanitized the Bank’s dark history when he stated:

“The Government was embarrassed by heavy commitments arising from the Maori Wars and leaned heavily on the Bank of New Zealand for assistance.”14

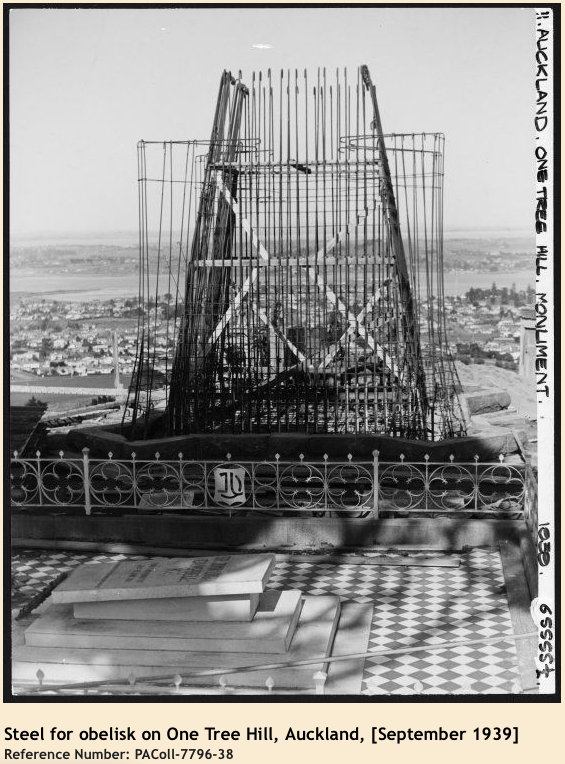

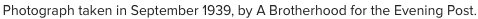

Crucially, one of the original trustees of the trustees and investors was the land-swindling Sir John Logan Campbell – whose grandfather was Sir James Campbell (1817-1912), fourth baronet of Aberuchill and Kilbryde – lent prestigé to the Bank of New Zealand venture. Poignantly, Sir John Logan Campbell, who arrived in Auckland in 1840, bequeathed £5000 for the construction of an overbearing 100 foot high Masonic obelisk to be built at the top of Maungakeikei in Cornwall Park. The construction, which began in 1939, came complete with a vanity tomb surrounded by a tiled checkered Masonic ‘floor’. At the base of the obelisk, a bronze Māori warrior statue was set, supposedly as a memorial to the ‘dying native race’ – because many settlers believed this was the fate of the indigenous Māori people.15 But because this Māori warrior faces Devonport, where the Royal New Zealand Navy took over Māori land and he ‘eyes’ another smaller Masonic obelisk that stands adjacent to the site of the now-demolished Masonic Hotel, and because this monument was finished in 1940 – the placement of the bronze Māori warrior was signifying that New Zealand was a Masonic Dominion, since the indigenous population was recovering by the time Sir John Logan Campbell became Mayor of Auckland for the Royal Landlord Tour of 1902. Moreover, because a bronze plaque incorrectly states that the Māori Treaty chiefs ceded sovereignty to Queen Victoria in 1840, the obelisk’s erection atop one of Papatūānuku’s maunga in the widely spread volcanic field of the Tamaki region in time for the centennial commemorations in 1940, therefore, signifies a Masonic conquest of ‘Maoriland’ – as New Zealand was colloquially known in the Colonial and Dominion-periods.

Masonic Humour: Steel re-enforcing for John Logan Campbell’s obelisk under construction, with vanity tomb in foreground on a Masonic checkered masonry, photographed by ‘A. Brotherhood’, 6 September 1939.

In 1870, Colonial Treasurer, Sir Julius Vogel, who was reputed to be a Freemason, proposed a £20 million loan for public works, and sent two landed-gentry Freemasons, Bro. Isaac Featherston and former New Zealand Company agent Bro. Francis Dillon Bell, to London to raise the funds.16 In other words, development money for infrastructure was withheld from New Zealand until the colony was consolidated into districts and provinces under Masonic control.

Māori were expected to labour for the Public Works Department. As one Parliamentary Journal recorded in 1871:

“The constant use of the pick and shovel will gradually wean [Māori] from their ancestral warlike tastes”.17

Denial of Sovereign Rights: In 1884, King Tawhiao Matutaera Potatau Te Wherowhero led a deputation to England to appeal to Queen Victoria for the return of Māori lands, the establishment of a Māori parliament and a commissioner to mediate between the parliaments. The second Māori King, pictured with his wife, Hera, was denied an audience with the Queen of the British Masonic Empire.

Landlessness was considered an effective measure to force Māori to assimilate into Pākehā society, should they survive. Indeed, it was physician Bro. Featherston who infamously said in 1856:

“The Maoris are dying out, and nothing can save them, Our plain duty, as good, compassionate colonists, is to smooth down their dying pillow. Then history will have nothing to reproach us with.”18

The Bank of New Zealand’s founders were a critical part of a confederacy that engineered a full-scale imperial war against Māori. The Bank’s primary founder Thomas Russell, who was the Minister of Colonial Defence during the Waikato War (1863-64), along with his law firm partner, Premiere Bro. Frederick Whitaker, and with BNZ investor Governor Bro. George Grey – were at the core of a Masonic Racketeering plot to consolidate British Freemasonry’s takeover of the New Zealand Colony.

=====

Editor’s Note: Please let me know if I have made any errors.

e: steveedwards555@gmail.com

Referenced Sources:

1 Chappell, N. M. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred: A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861-1961. Auckland, NZ: Bank of New Zealand.

2 Graeme Hunt. (2000). The Rich List: Wealth and Enterprise 1820-2000, p. 84; Chappell, N. M. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred: A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861-1961, p. 82-85.

3 James Belich. (1988). The New Zealand Wars: And the Victorian View of Racial Conflict; Danny Keenan. (2009). Wars without End: The Land Wars in Nineteenth-century New Zealand; Tony Simpson (1986). Te Riri Pakeha: The White Man’s Anger. Auckland, NZ: Hodder and Stoughton; Belich. (1988). The New Zealand Wars: And the Victorian View of Racial Conflict; Dom Felice Vaggioli. (2000 [1896]). History of New Zealand and its Inhabitants, Vol. II. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press.

4 Snoopman. (25 April 2017). “The Masonic New Zealand Wars: Freemasonry as a Secret Mechanism of Imperial Conquest During the ‘Native Troubles’” Retrieved from https://snoopman.net.nz/2017/04/25/the-masonic-new-zealand-wars/https://snoopman.net.nz/2017/04/25/the-masonic-new-zealand-wars/

5 Hunt, Graeme. (2000). The Rich List: Wealth and Enterprise 1820-2000, p. 80-105; A. H. McLintock (Ed.). (1966). An Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Vol. III, p. 652. Wellington, New Zealand: R.E. Owen, Government Printer.

6 A.N. Field. (1939). The Truth About New Zealand, p. 8; Bro F. G. Northern. (1971). History of the Grand Lodge of New Zealand 1890-1970, p.5-6, 147. Gisborne: V.W. Bro. P. J Oliver/Te Rau Press.

7Graham, Jeanine. (1983). Frederick Weld, p. 67. Auckland University Press; Hunt (2000): 72-73, 98; Bro. Frans van Zoggel. (2006). Famous Sons of the Widow: 49-51.

8 McLintock (Ed.). (1966). An Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Vol. III, p.p. 158-159; 651-653.

9 Chappell. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred.

10 Chappell. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred, p. 9-10.

11 Michael King (2008). Maori: A Photographic and Social History. p. 50; Simpson 1986: Te Riri Pakeha, p.166; Vaggaoli (2000). AHistory of New Zealand and Its Inhabitants, p.187.

12 Chappell. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred, p. 81.

13 Chappell, N. M. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred, p. 102; J.B. Condliffe (1927). A Short History of New Zealand, p. 116;Malcolm McKinnon. (2013). Treasury: A History of the New Zealand Treasury 1840-2000.

14 Also quoted In: Graham, Jeanine. (1983). Frederick Weld, p. 75-76. Auckland University Press.

15 Chappell. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred, 18-19, 31, 393-394, 397; Hunt. (2000) The Rich List: Wealth and Enterprise 1820-2000, p. 84; Grant, David (1997): Bulls, Bears & Elephants: A History of the New Zealand Stock Exchange, Fn4 p. 381; Bro. Frans van Zoggel (2006). Famous Sons of the Widow, p.69-71.

16 Bateman. (1989). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of New Zealand, p.1284. Auckland, NZ: Bateman; Weston. (1942). The Pacific Lodge.

17 Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives. (1871). Vol. 1 D. 1, p. 19. No. 29. In: Rosslyn J. Noonan. (1970). By Design: A Brief History of the Public Works Department – Ministry of Works 1897-1970, p. 30.

18 Ian Pool and Tahu Kukutai (5 May 2011). ‘Taupori Māori – Māori population change – Decades of despair, 1840–1900’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/taupori-maori-maori-population-change/page-2 (accessed 12 January 2017); Keenan. (2009). Wars without End, p. 67; Simpson. (1979). Te Riri Pakeha, p. 99.