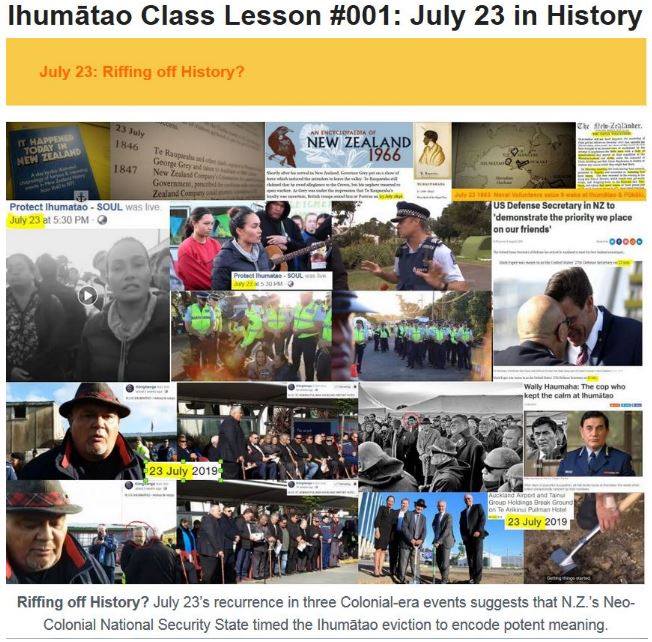

Dispatch from Ihumātao #001

By Snoopman

A Māori King Elected – 1857

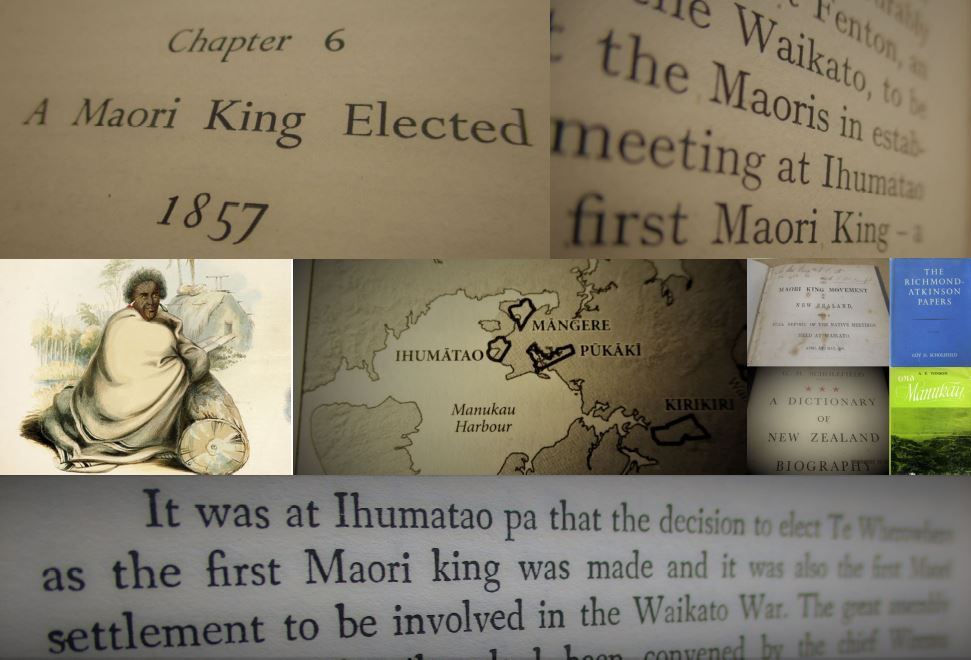

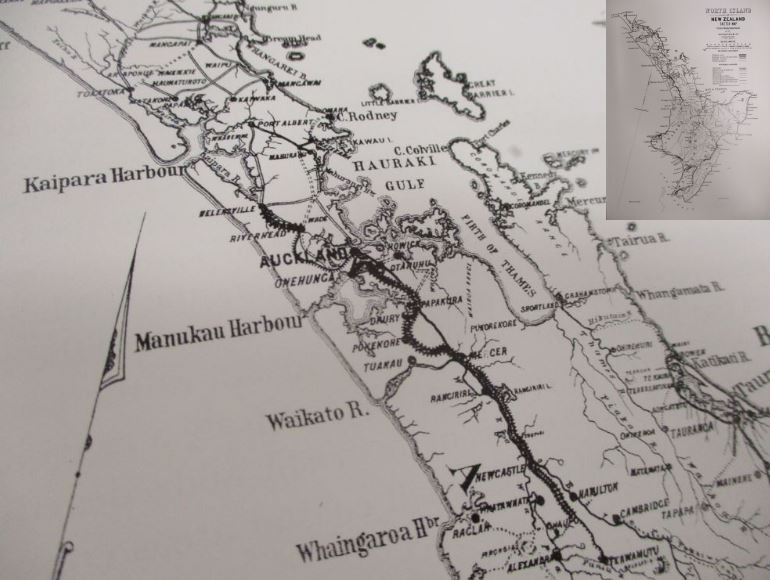

In the Colonial era, Chief Te Wherowhero was elected as the first Māori King in June 1857 at Ihumātao Village on a north east shore of the Manukau Harbour, on the island of Te Ika-a-Māui, or the North Island, of New Zealand.1

The election of New Zealand’s first Māori King at Ihumātao makes the history-laden volcanic coastal peninsula landscape even more significant than is currently appreciated.

Chief Te Wherowhero (circa 1770-1860) accepted his selection to be the first to lead the kingitanga very reluctantly. He was installed as King Potatau Te Wherowhero on June 2 1858 at Ngāruawāhia, located at the confluence of the Waipa and Waikato rivers, or awa.

The Kingitanga, or Māori King ‘kingite’ movement, was a response by the indigenous people of New Zealand adapting to the challenges of a Settler Government. These challenges included pressures to sell whenua to land swindling Colonial Crown agents, settlement land companies promising tracts of land to migrant ship passengers, and assorted confederacies of settlers adept at playing games of divide and conquer against ‘the natives’.

Tainui Waka at Ihumātao

Ihumātao is also a place of national significance because the whenua, or land, is the second landing place of the Tainui waka that travelled amid a wave of migration from Ha’waiiki about 1300AD. The Tainui waka travelled into the Hauraki Gulf, up the Tamaki Estuary, and crossed a one-mile portage overland at the Ōtāhuhu isthmus, where the canoe was re-submerged into the Manukau Harbour and cruised to the shore at Ihumātao.

The vast harbour of Manukau was already known to Māori navigators since their forebears, Te Ākitai Waiohua tribe, had discovered New Zealand about 900AD.2 Some of the people of Ihumātao village are of the Ngati Tamaoho hapū, a remnant of the Te Ākitai Waiohua tribe. In addition to Te Ākitai, other mana whenua include: Te Ahiwaru, Te Wai-o-Hua, Waikato-Tainui, Ngāti-Whatua, and Te Kawerau a Maki – whom came to live with the community in the 1930s.3

It is said that Te Ākitai Waiohua iwi named the region comprising of two harbours, epic kauri rain forested ranges and a vast volcanic field comprising 53 volcanoes, labrynthine volcanic caverns, caves and solidified lava flows – Tamaki Makaurau. This would mean the name had been in continuous use for 890 years before Royal Navy Captain and Governor, William Hobson, usurped the name Tamaki Makaurau with Auckland – in the grand imperial tradition of conquest to acknowledge his patron, the Vice-Roy of India, Lord Auckland. Governor Hobson performed a Discovery Doctrine ‘Possession Ritual’ on September 18th 1840 in Commercial Bay by Point Britomart, which became Fort Britomart, and was named after H.M.S. Britomart, the British Royal Navy warship that had surveyed the Waitemata Harbour in 1841.4 Thus, Tamaki Makaurau became more known by its English alias, and eventually grew to become the largest city in the South Pacific Neo-Colonial Realm of New Zealand.

In 1835, Te Wherowhero – who was of the Waikato Ngati Mahuta tribe and descendant of Tapaue from Hoturoa of the Tainui canoe – personally escorted Te Ākitai Waiohua, Ngāti Whatua and various Tainui groups that had been displaced for nearly a decade from the Tamaki region during the horrific inter-tribal Musket Wars.

At some point, the Ngati Tamaoho hapū ownership of land was disputed by another tribe and so Ngati Tamaoho hapū formed a village at Ihumātao on the north east shore of the Manukau in the place formerly known as Taotaoroa – that became known as the Mangere district – to keep the peace.6

In 1845, the Pehiakura Methodist Mission Station was established on the South Western Shore of the Manukau Harbour (also called the Pollok Settlement for a time). Also in the mid-to-late 1840s, the Ihumātao Wesleyan Mission Station was built with the help of what was described as Maori ‘free labour’ – in Reverend William Morley’s 1900 tome, The History of Methodism in New Zealand.

In 1849, Chief Te Wherowhero moved to the site of seasonal kainga at Mangere to establish a Maori ‘fencible’ settlement supposedly to place his mana over Auckland, after he was approached by Governor George Grey.5 This ‘peacekeeping bond’ followed Grey’s establishment of four Fencible Settlers military settlements – Onehunga, Otahuhu, Panmure and Howick in 1847.

Monster Maori Gathering

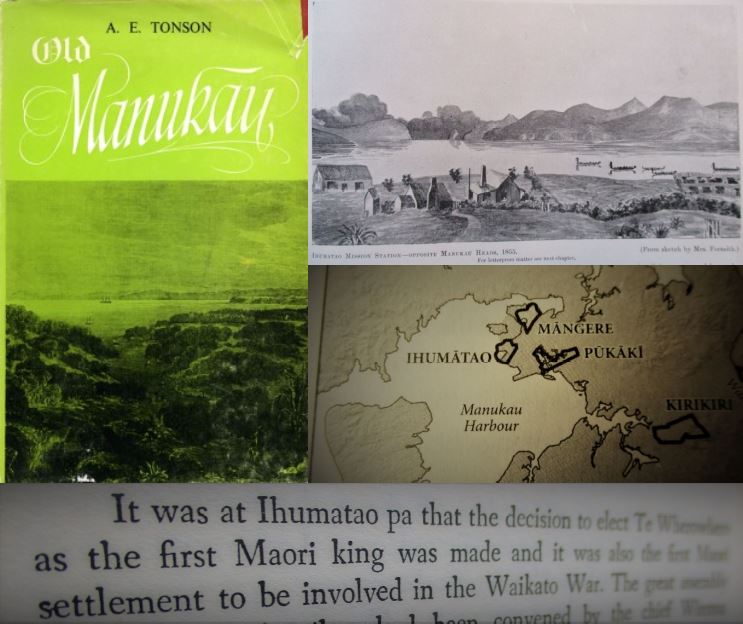

In his 1966 book Old Manukau, historian A. E. Tonson described the 1857 hui at Ihumātao that culminated in Te Wherowhero being elected to the position of first Māori King as a “monster Maori gathering”. This meeting, which began as a tangi on May 22nd 1857 to remember Epiha Putini, who was a high profile Ngati Tamaoho leader, morphed into a political meeting in accordance with tikanga, or custom, at funerals of important Māori.7 ‘The natives’ – as the indigenous people of Aotearoa/New Zealand were frequently called in private letters between missionaries, official Crown correspondences and newspaper reports in the Colonial-era – journeyed from a prior kingitanga meeting in Rangariri by the Waikato River and many parts of the North Island, to decide on a Māori king and to settle old disputes among the tribes.

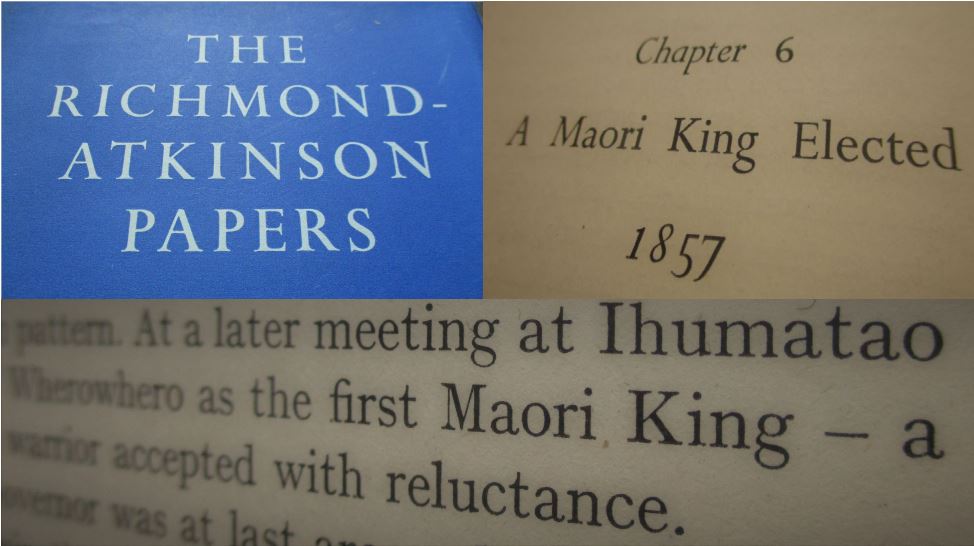

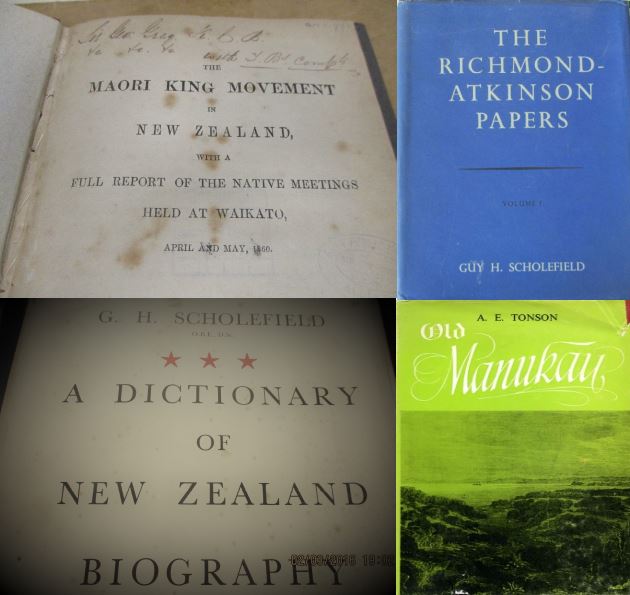

In his 1864 book, The Maori King: The Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives, John Gorst wrote that the meeting discussed the establishment of a Māori king with a separate sovereignty.3 Government historian Guy H. Scholefield stated in his two-volume The Richmond-Atkinson Papers published in 1960, that it was at Ihumātao that “the chiefs chose Potatau Te Wherowhero as the first Maori King – a dignity that this venerable warrior accepted with reluctance.”8

In the Department of Internal Affairs’ 1940 Dictionary of New Zealand Biography – edited by Guy Scholefield – it stated that it was “not without reluctance that Te Wherowhereo in 1857 accepted election as the first Maori ‘ King. ’ ”

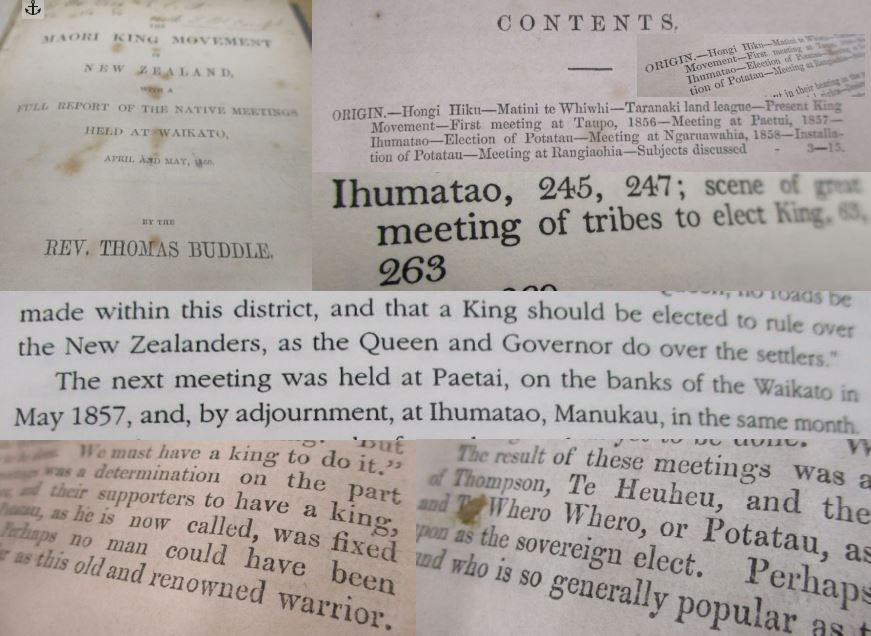

In the first report about the kingitanga, The Maori King Movement in New Zealand published in 1860, Wesleyan Reverend Thomas Buddle states that “Te Whero Whero, or Potatau, as he is now called, was fixed upon as the sovereign elect” at Ihumatao in 1857.9

Paramount chief of the Ngāti Tuwhareto tribe, Te Heuheu Tukino IV, (1821-1888) sponsored a kingitanga hui at Pūkawa Marae, near Turangi, in November 1856 – and suggested Te Wherowhero. However, Te Wherowhero flat out refused and it took seven hui before Te Wherowhero agreed.10

In Old Manukau, Tonson not only stated the decision to elect Te Wherowhero as the first Māori King was made at Ihumātao.

Poignantly, Tonson also added Ihumātao, “was also the first Maori settlement to be involved in the Waikato war”. Writing in his 1900 tome The History of Methodism in New Zealand with like meagerness of detail, Methodist historian Reverend William Morley stated the Ihumātao was prosperous “until the war troubles of 1863 broke up the settlement”.11

Forebodingly, Reverend Buddle – who witnessed Te Wherowhero’s election as king, along with Bishop Samuel Marsden, C.O. Davis, Mr. Stephen Westney and other Protestant Missionaries and ‘gentlemen’ – recorded that the Protestant Missionaries warned Māori that the Pākehā would tear them to pieces.12

The election of King Potatau Te Wherowhero as New Zealand’s first Māori King at Ihumātao adds huge significance to the history-laden volcanic coastal peninsula landscape.

=====

Editor’s Note: Please let me know if I have made any errors.

e: steveedwards555@gmail.com

Referenced Sources

1 Reverend Thomas Buddle. (1860). The Maori King Movement in New Zealand, p. 3, 10, 12; Guy H. Scholefield (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand, p. 490. Department of Internal Affairs.; Guy H. Scholefield. (1960). The Richmond-Atkinson Papers, p.250. Wellington; New Zealand: R.E. Owen; A. E. Tonson. (1966). Old Manukau, p. 103. Onehunga, Auckland; New Zealand: Tonson Publishing House.

2 TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA HISTORY. Retrieved from http://www.teakitai.com/index.php/history

3 Te Ākitai Waiohua. (2012). Te Ākitai: Cultural Impact Statement by Te Ākitai Waiohua for The Southern Consortium, p. 15; Tim McCreanor, Fances Hancock & Nicola Short. (2018). The Mounting Crisis at Ihumatao: A High Cost Special Housing Area or a Cultural Heritage Landscape for Future Generations. CounterFutures. School of Social and Cultural Studies, Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved from http://counterfutures.nz/6/McCREANOR%20HANCOCK%20SHORT.pdf

4 John Barr. (1922). The City of Auckland New Zealand 1840-1920, p. 35, 39. Whitcombe & Tombs Limited.

5 New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero – Report for a Historic Place Pōtatau Te Wherowhero Monument and Kīngitanga Reserve, NGĀRUAWĀHIA (List No. 0757, Category 1) p. 10. Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/-/media/f066c1f347a84d7690bdff062678623a.ashx

6 Rev. William Morley. (1900). The History of Methodism in New Zealand. p. 103. McKee & Co.

7 Vincent O’Malley. (2015): The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, p 83; See also: TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA HISTORY http://www.teakitai.com/index.php/history

3 John Gorst. (1864). The Maori King: The Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives, p. 63.

8 Scholefield. (1960). The Richmond-Atkinson Papers, p.250; Scholefield. (1940) A Dictionary of New Zealand, p. 490.

9 Rev. Thomas Buddle. (1860). The Maori King Movement in New Zealand, p. 3, 10, 12.

10 Keenan, Danny, “The Kingitanga” in Mana, The Maori News magazine for all New Zealanders, issue 50, pages 63-68.

11 Gorst (1864). The Maori King p. 63.

12 Reverend William Morley. (1900). The History of Methodism in New Zealand, p.104.