During and after the Waikato War of 1863-64 in New Zealand, well-connected Wesleyan Methodists capitalized on vacated Māori land on the Ihumātao Peninsula by leasing ‘Native Reserves’ and buying ‘Waste Land’ lots to run cattle. These incursions by two Wesleyan families – the Vercoes and the Wallaces – occurred with the knowledge of Wesleyan reverends including Rev. Henry H. Lawry and Rev. Thomas Buddle. This Wesleyan takeover happened against a backdrop of the escalation of the New Zealand Wars, which could not have unfolded without a £3 million war loan brokered by the ‘terrible-two’ year-old Bank of New Zealand – whose primary founder was the Wesleyan lay preacher, Thomas Russell, who was also a partner in the law firm Whitaker & Russell. Reverend Thomas Buddle – who witnessed the election of King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero at Ihumātao in mid-1857 and wrote the first full report on the development of the Kingitanga – worked for Whitaker & Russell and eventually became a partner. This betrayal by Wesleyan Methodists upended the relationship with the mana whenua of Ihumātao, whom had built the 8-acre Wesleyan Mission Station on the 1100-acre Ihumātao Peninsula in the mid-to-late 1840s. Upon their return to Ihumātao after the end of the Waikato War, they were reduced to a 50-acre Native Reservation to eke out a subsistence existence.

Dispatch from Ihumātao #004

By Snoopman

A Great Softening

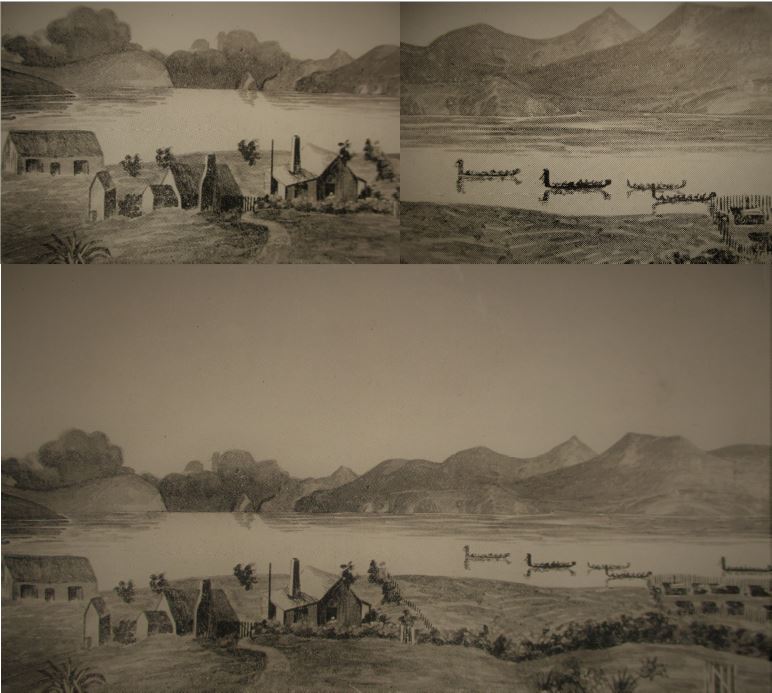

A long-abandoned eight acre Māori-built Wesleyan Methodist Mission Station located at Ihumātao is linked to a dark chapter of Ihumātao.

The Ihumātao Mission Station – which was located on a north east shore of the Manukau Harbour, on the island of Te Ika-a-Māui, or the North Island, of New Zealand – was abandoned and vandalized after the mana whenua of Ihumātao village were served an eviction notice mid-July 1863.

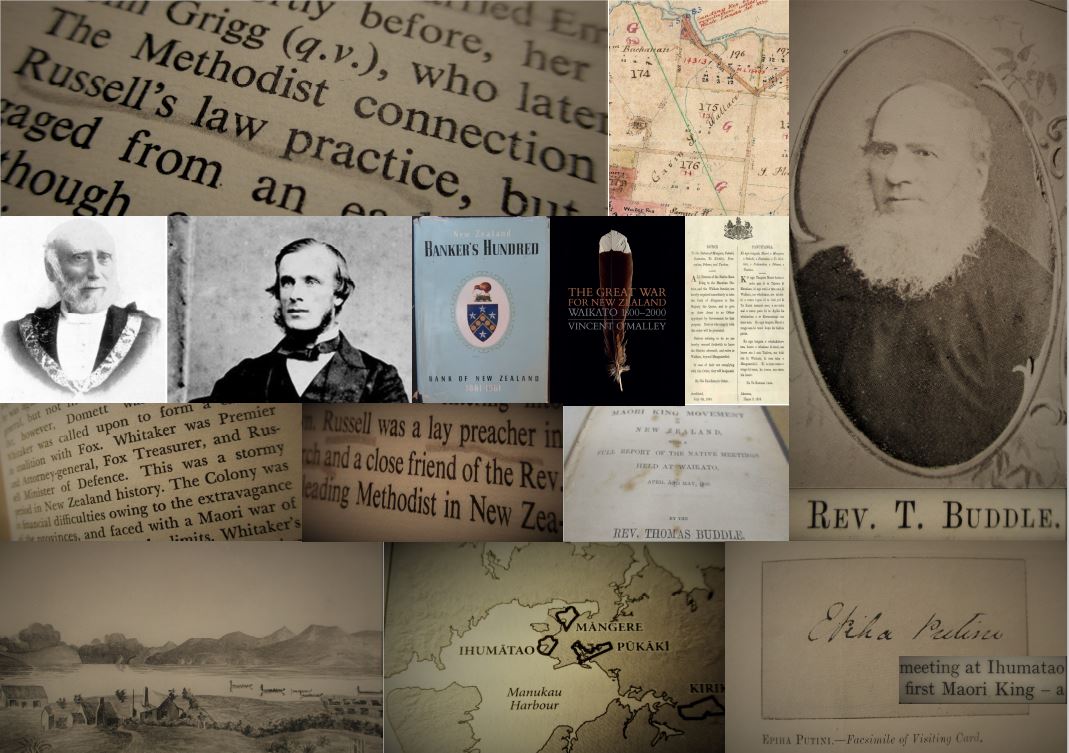

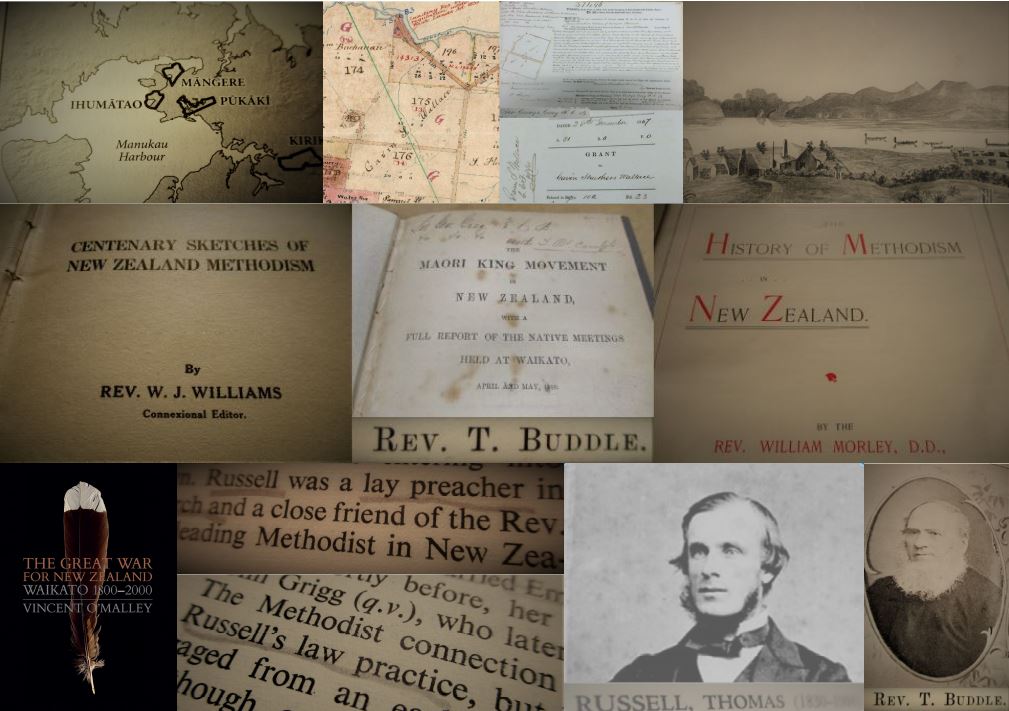

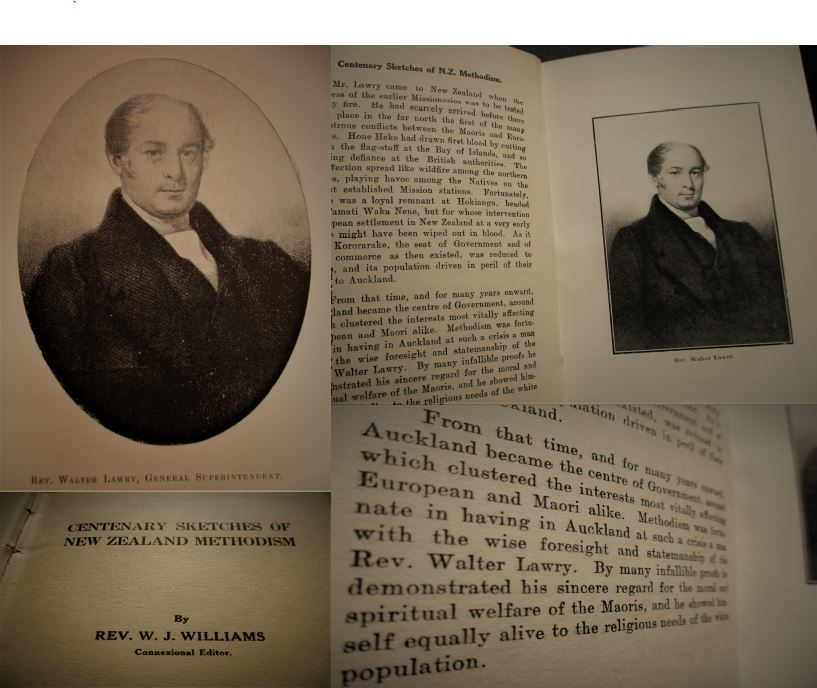

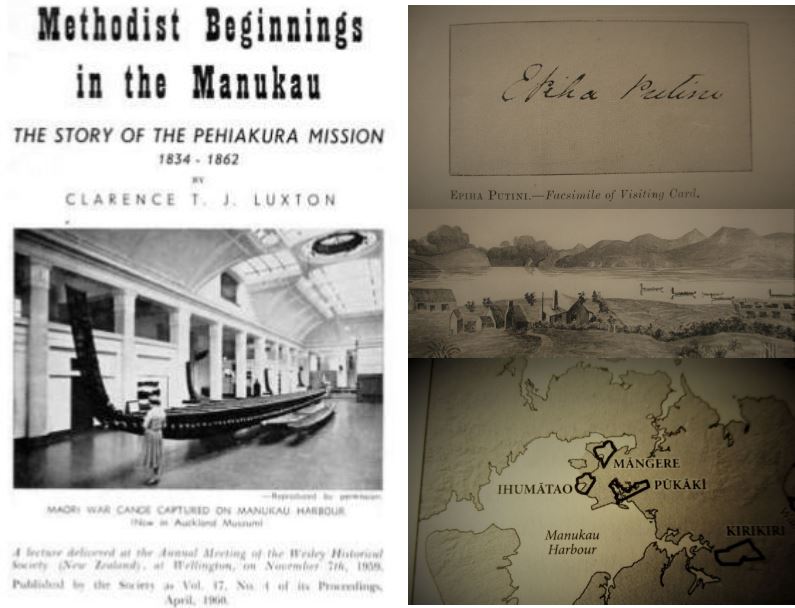

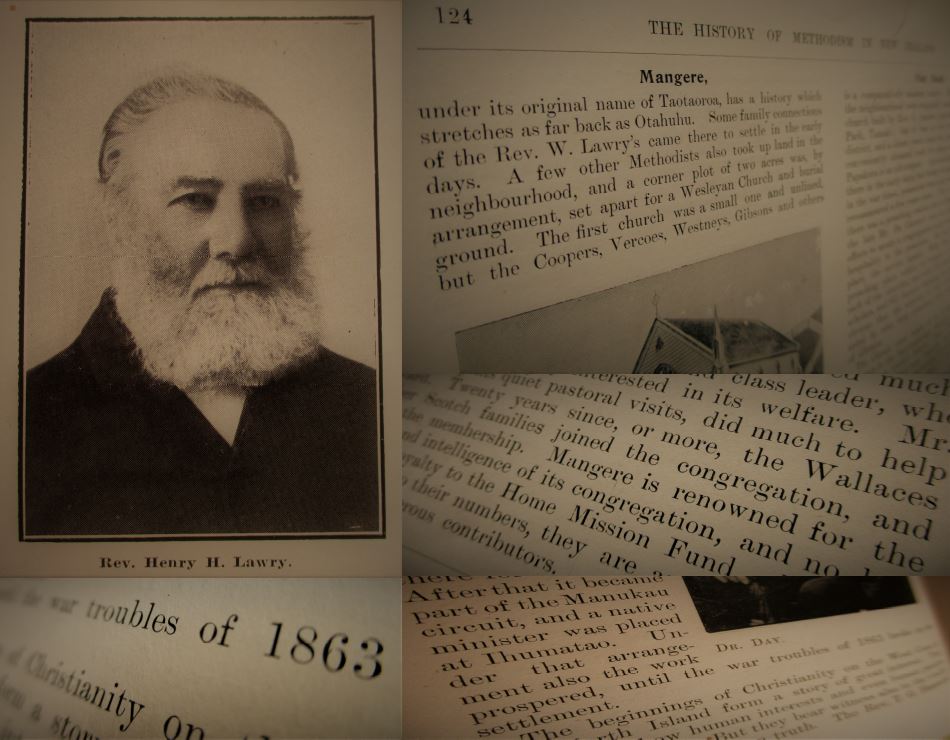

At the time of the evictions of Manukau Māori in mid-July 1863, this Manukau Circuit was in the charge of Reverend. Henry H. Lawry, a son of Rev. Walter Lawry – who brought Methodism to the Manukau in 1845.1 The Manukau Circuit included the Pehiakura Methodist Mission Station, which was located on the Awhitu Peninsula, on the Southern shores of the Manukau Harbour.2

During Reverend Walter Lawry’s time, the Ihumātao Methodist Mission was built with ‘native free labour’, including a three-bedroom weatherboard house, and a school in the mid-to late 1840s.3

In the mid-1840s, Ngati Te Ata and Ngati Tamaoho fought over disputed boundaries on the Awhitu Peninsula. By 1849, chief Te Rangitaahua Ngamuka, also known by his baptismal name Epiha Putini, moved with many of his people from Pehiakura to Ihumātao – to keep the peace.

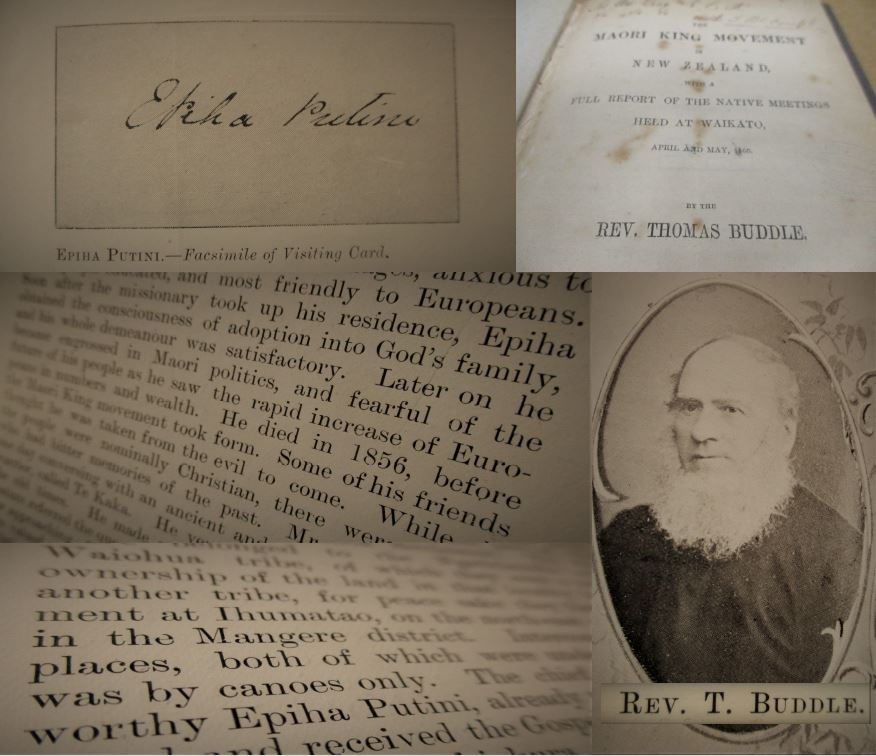

In mid-1857, the village of Ihumātao found itself hosting a huge Kingitanga hui after a commemorative tangi to remember Epiha Putini – who was a high profile Ngāti Tamaoho leader – and morphed into a political meeting in accordance with tikanga, or custom, at funerals of important Māori.4 The son of Chief Te Tuhi, Te Rangitaahua Ngamuka was baptized as Epiha Putini on October 18th 1835, which was the Māori form of the name, Jabez Bunting, the London Church Mission Society’s secretary. Putini became a Wesleyan preacher and by the early 1850s was concerned about Māori land loss and increasing influx of Europeans, but died young in 1856, aged 40.

It is rather ironic, therefore, that in marking the passing of a ‘Native’ Wesleyan preacher of such chiefly stature – whom was well regarded by his people as well as the settlers – that the occasion became a majorly historic Kingitanga hui – especially given that he was concerned about Māori land loss and immigration – as Clarence T. J. Luxton noted in his monograph, “Methodist Beginning in the Manukau: The Story of Pehiakura Mission, 1834-1862”. It’s a pity Luxton did not follow up with a book titled, “Methodist Consolidation in the Manukau: The Story of Ihumātao Mission, 1846-1863 and its Aftermath.”

As The Snoopman reported in his “Dispatch from Ihumātao #001 – The Kingitanga Connection” – Ihumātao was the place where the first Māori King, Chief Te Wherowhero (circa 1770-1860), was elected as King Pōtatau in June 1857.5

The Kingitanga, or Māori King ‘kingite’ movement, was a response by the indigenous people of New Zealand adapting to the challenges of a Settler Government. These challenges included pressures to sell whenua to land swindling Colonial Crown agents, settlement land companies promising tracts of land to migrant ship passengers, and assorted confederacies of settlers adept at playing games of divide and conquer against ‘the natives’.

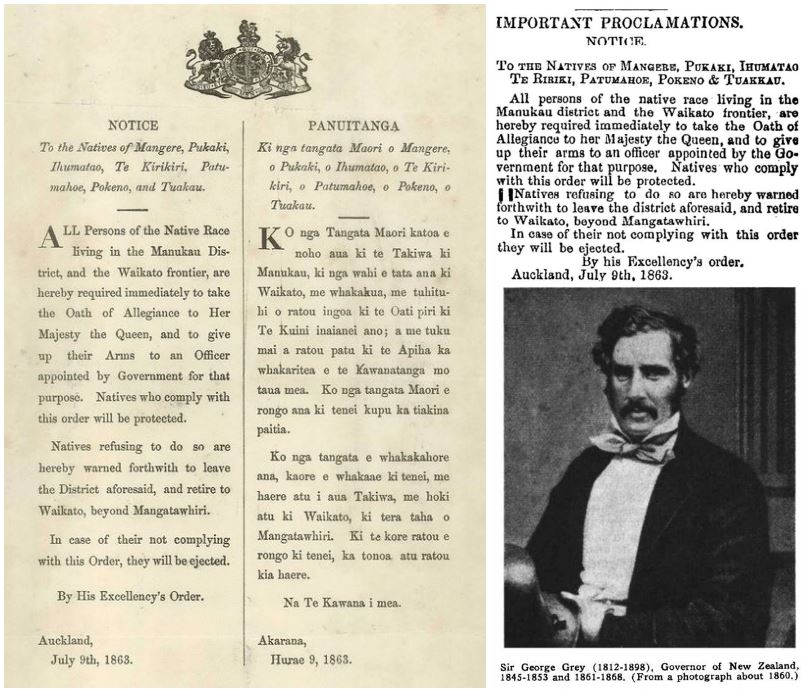

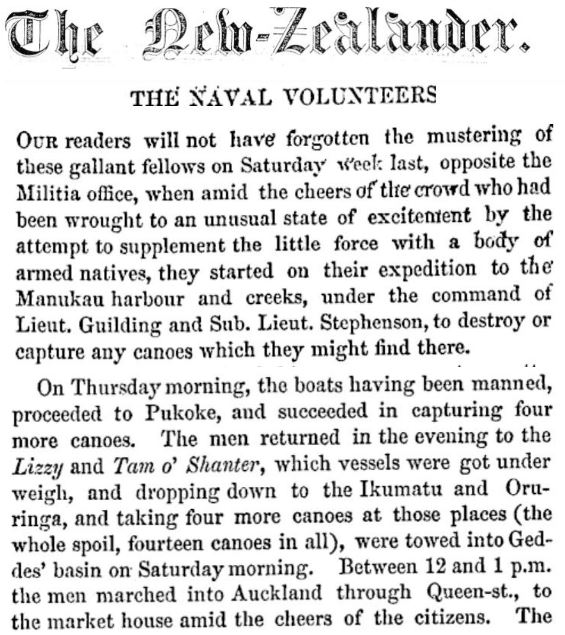

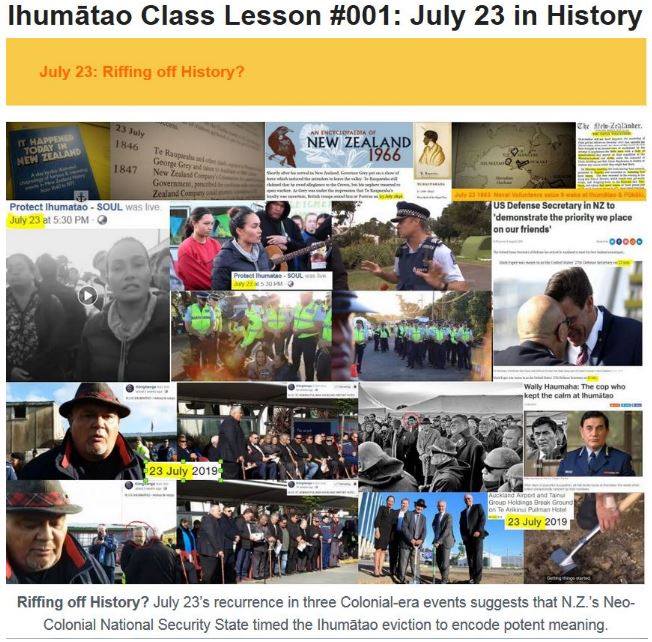

It was, therefore, also deeply ironic that six years later, that the mana whenua of the Ihumātao were forced to vacate their papakāinga, or communal village, when Freemason Governor Bro. George Grey’s underlings delivered the Governor’s ‘eviction notice’. This ultimatum by Proclamation, dated 9 July 1863, demanded Māori of the Manukau District and elsewhere in the southern parts of the Tamaki region to pledge loyalty to Queen Victoria and to hand in their weapons.6 These terms were an affront to the sovereign system of chiefs and chieftainess whose mana was based in hapū or whanau groups, and iwi or tribes, as well as the whenua and connection to the spiritual world – as Freemason Bro. Grey well knew. Because the Auckland Naval Volunteers confiscated four canoes from Ihumātao and nearby Oruarangi on July 23 1863 while the manu whenua were selling their livestock, produce and packing – the Māori of Ihumātao were forced to walk to the Waikato.7

While Māori of the Manukau district were selling what livestock, produce and other possessions they could before they left, 17 waka of the Manukau District were confiscated by 39 Auckland Naval Volunteers and twenty-five ‘friendly natives’ in a week long expedition. According to historian T. B. Byrne in his 1991 book, Wing of the Manukau, the civil and military authorities viewed the Manukau Harbour as a security risk, since the port at Onehunga was considered “Auckland’s backdoor”.

The Double Life of a Colonial Defence Minister

On 18 February 1864, the New Zealander reported upon the destruction of the village, or papa kāinga, and Wesleyan Methodist Mission station at ‘Ihumatau’ [sic]. This report was recounted by Professor Harold Miller in his 1966 book, Race Conflict in New Zealand, 1814-1865. Miller quoted the New Zealander newspaper:

“One settler later observed that the Ihumatau [sic] natives … were good neighbours and very much respected by the settlers around; nearly all their houses and fences had been destroyed; their church gutted, the bell, sashes, door and communion tables and even the floor torn up and taken away; and how their land is to be occupied by Mr. [Thomas] Russell’s brother-in-law”.8

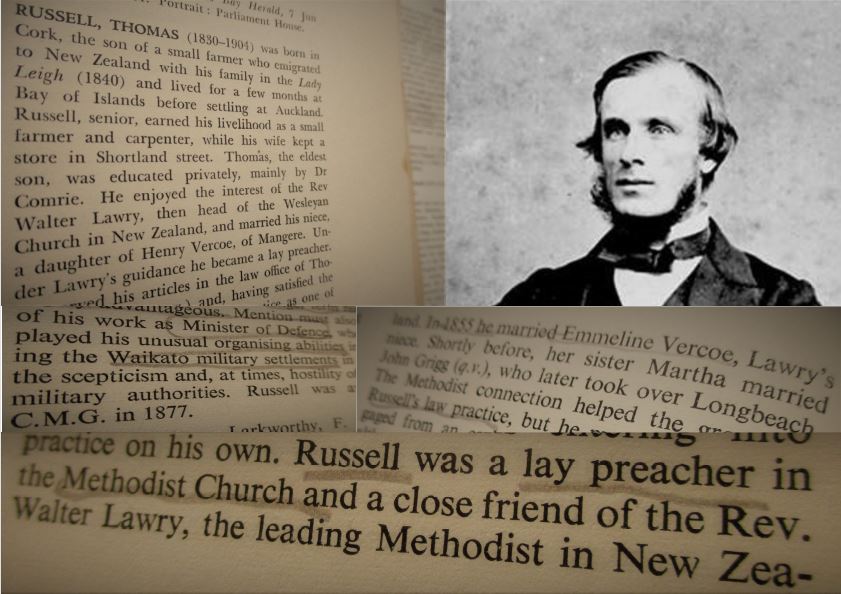

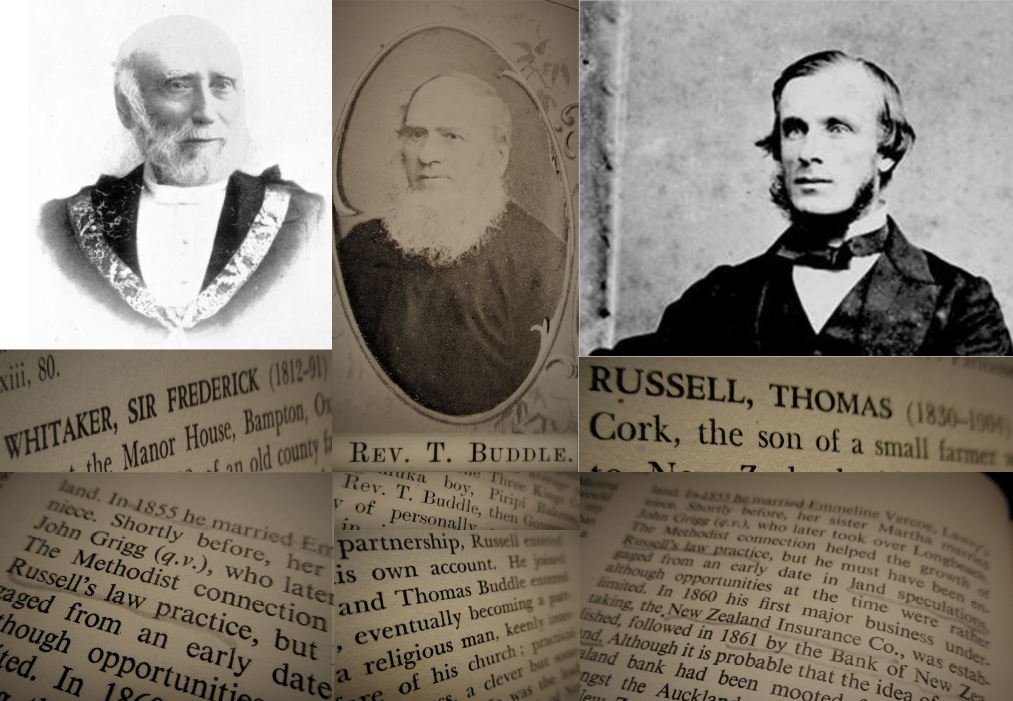

The Thomas Russell referred to in the above quote became a Wesleyan lay preacher under the guidance his close friend, Reverend Walter Lawry, the head Methodist Minister of the Manakau Circuit and General Superintendent of the Wesleyan Mission in New Zealand.9

In this position as Rev Lawry’s protégé, much of the Weyleyan mission’s legal work came his way, and Russell managed some of the Methodist Church’s accumulated funds, and through this work “amassed a considerable sum of money” in his own right.10 In the 1966 edition of An Encyclopedia of New Zealand, edited by Government historian, A. H McLintock, it stated, “The Methodist Connection helped the growth of Russell’s law practice.”

Indeed, Thomas Russell had something of a double-life.

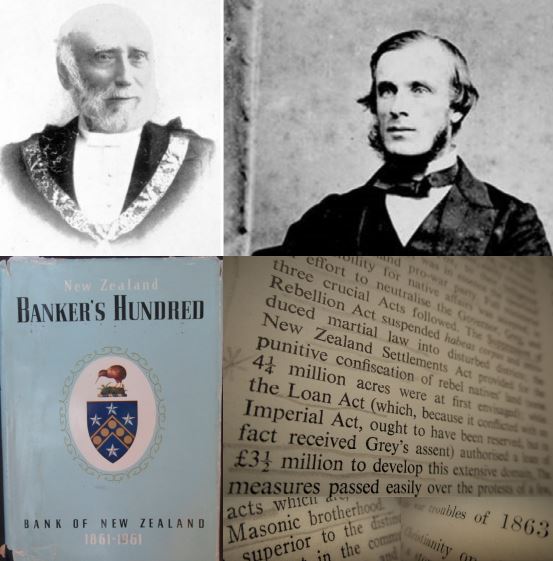

At the time of the evictions of Māori from Manukau district, including ‘the Natives’ of Ihumātao – Russell was the Minister of Colonial Defence (1863-64). During the Waikato War of 1863-64, Thomas Russell’s law firm business partner, Freemason Bro. Frederick Whitaker – was also the Premiere of New Zealand, as well as the Attorney General.11

By occupying these key political positions prior to and during the Waikato War of 1863-64, the Bank of New Zealand’s primary founder Thomas Russell and his law firm partner, Freemason Bro. Frederick Whitaker, were able to drive the ‘wedge of war’ deeper with three more parliamentary acts. The Suppression of Rebellion Act of 1863 cast Māori as insurrectionists, while the New Zealand Settlement Act ‘legalized’ the establishment of military towns on confiscated land, and the New Zealand Loan Act authorized ‘borrowing’ of three million pounds from the Imperial Government to consolidate this far-flung colony of the British Masonic Empire.

Moreover, Thomas Russell was the primary founder of the Bank of New Zealand – which was established by Royal Charter and Colonial Government legislation in 1861 – and brokered finance of £3 million from the Imperial Government to escalate the New Zealand Wars after the First Taranaki War (1860-61) ended inconclusively.12

Cronyism in Confiscations – 1865-1866

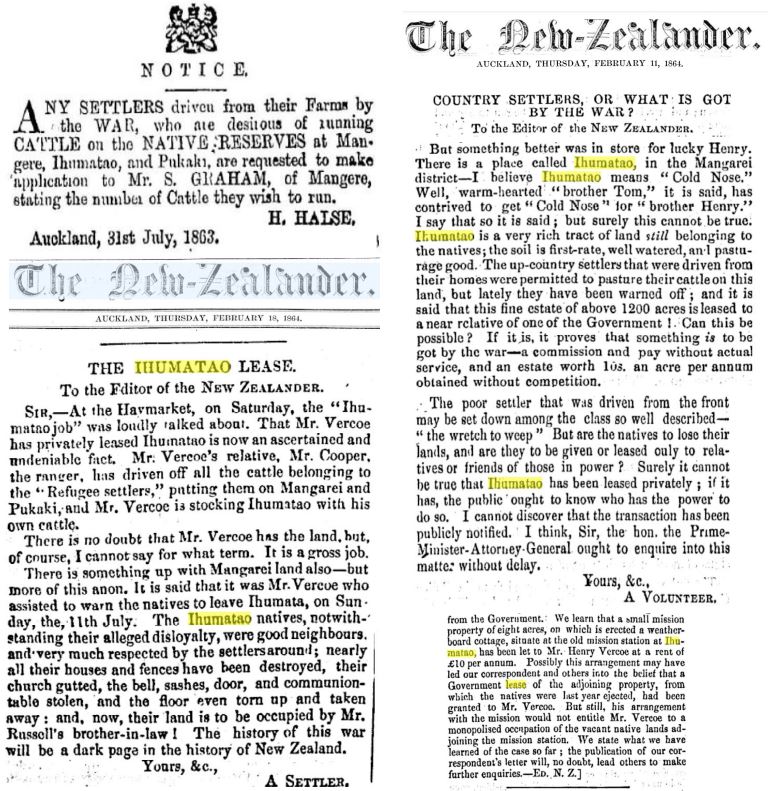

Russell, who had married Emmeline Vercoe, daughter of Henry John Vercoe and Anna Vercoe (nee Lawry) of Mangere, and Rev. Walter Lawry’s niece, in a wedding ceremony officiated by Rev. Walter Lawry in 1855.13 Thus, the marriage was ministered by Thomas Russell’s mother-in-law’s brother, meaning Rev. Walter Lawry was Thomas Russell’s new wife’s uncle. This Lawry-Vercoe Methodist connection becomes important to the deep history of Ihumātao because by February 1864, Emmiline’s brother Henry Vercoe and, therefore, Thomas Russell’s brother-in-law – was grazing his cattle on Ihumātao land – land that was officially described as ‘Native Reserves’ on 31st July 1863 – barely a fortnight into the Waikato War.

In his 1966 book, Race Conflict in New Zealand, 1814-1865, historian Harold Miller quoted a passage from a letter to the editor of the New Zealander newspaper dated 18 February 1864:

“SIR, – At the Haymarket, on Saturday, the “Ihumatao job” was loudly talked about. That Mr. Vercoe has privately leased Ihumatao is now ascertained and undeniable fact. Mr. Vercoe’s relative, Mr Cooper, the ranger, has driven off all the cattle belonging to the “Refugee settlers,” and putting them on Mangarei and Pukaki, and Mr. Vercoe is stocking Ihumatao with his own cattle.”14

The correspondent – “A Settler” – names Mr. Vercoe as Mr. Russell’s brother-in-law in the whole letter, sourced from Papers Past, which provides the context that this “dark page in the history of New Zealand” was discussed “loudly” at the Haymarket the previous Saturday. This Mr. Vercoe is Henry Walter Vercoe (1835-1919) – son of Henry John Vercoe (1799-1862) and Anna Vercoe (1801-1862, formerly Lawry). The ranger, Mr Cooper, named as Henry Walter Vercoe’s accomplice in clearing the land of “Refugee settlers” was of the Wesleyan Methodist Cooper family.

This ‘private lease’ followed a public gazetted notice dated 31st July 1863, by Grey’s official Henry Halse. The Masonic-driven Colonial Capitalist take-over of Ihumātao, Mangere, and Pukaki proceeded swiftly.

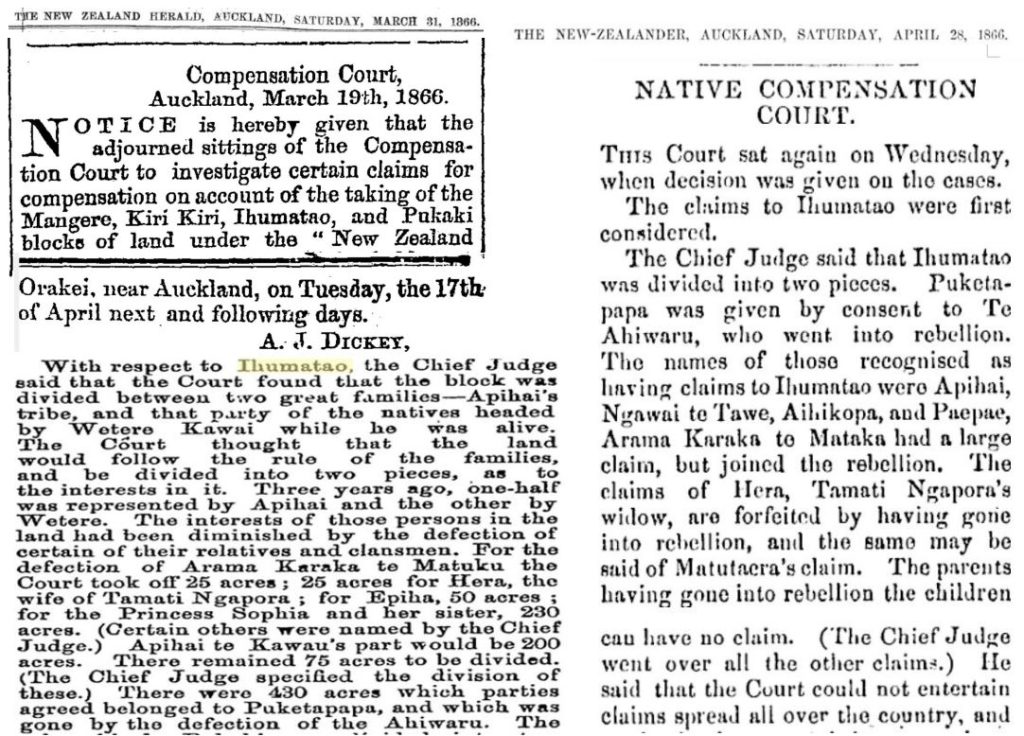

In March, April and May of 1866, the Native Compensation Court ‘investigated claims in relation to Ihumātao, as well as Mangere, Kiri Kiri and Pukaki. The Chief Judge ruled various acreages within the Ihumātao Block were “gone” from Māori families whom were deemed to have been in “rebellion”, and by their “defection” had forfeited their ancestral lands.

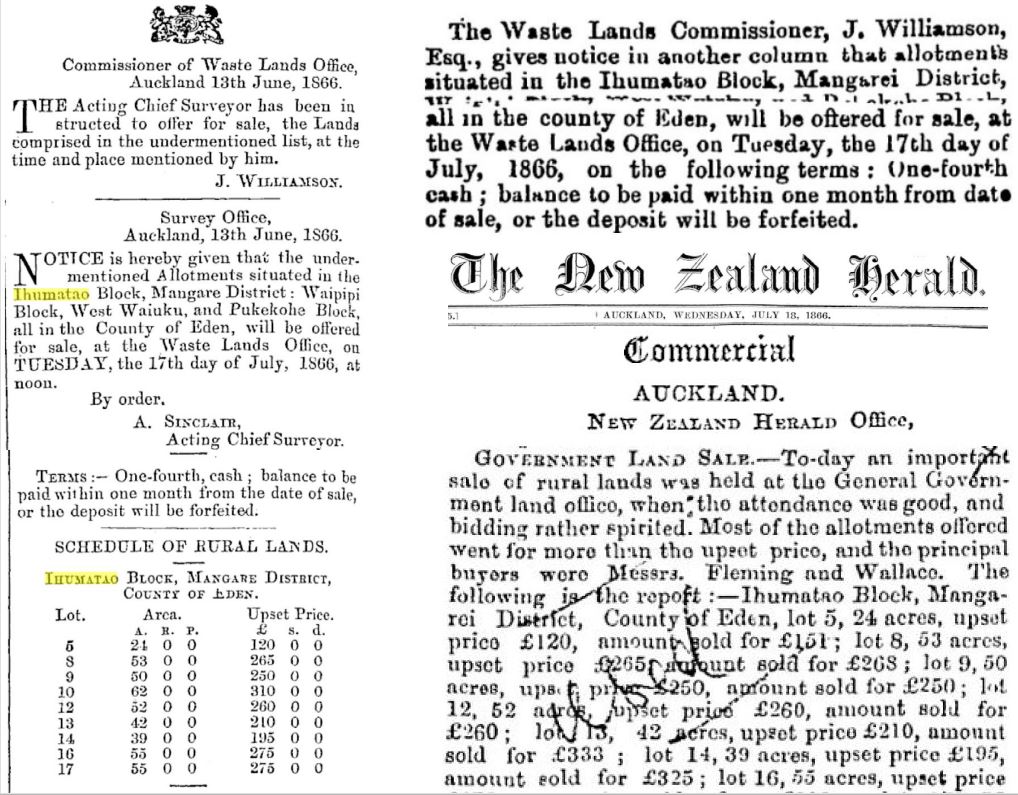

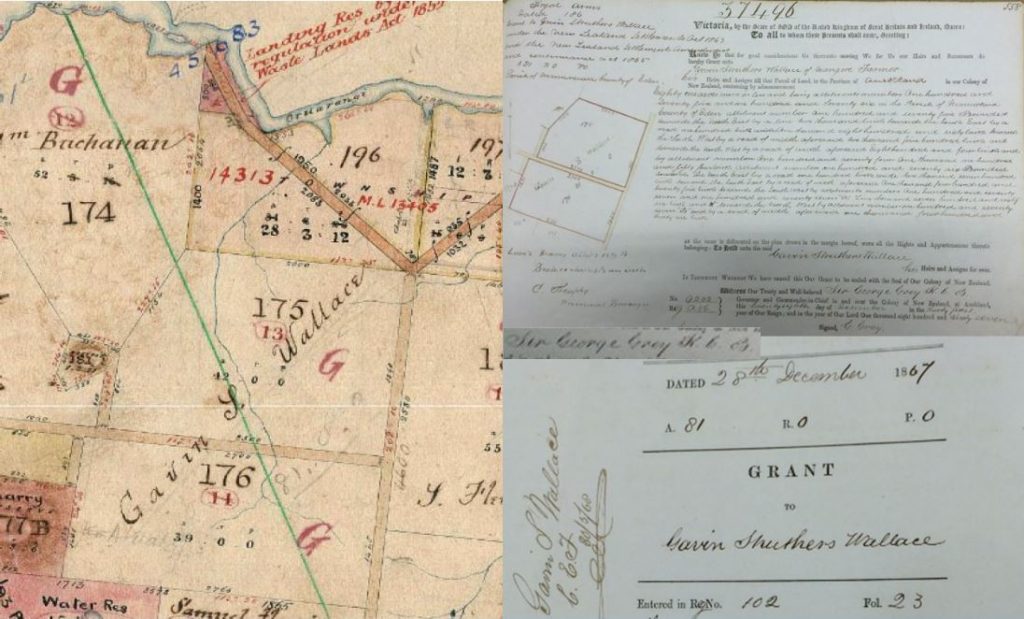

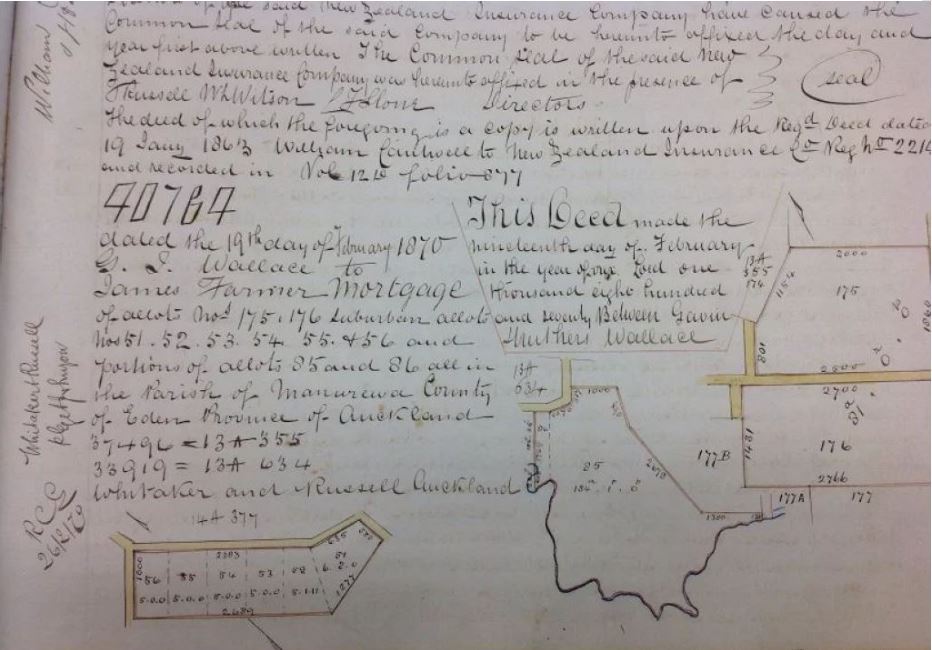

Three years after the evictions, on 17th of July 1866, two parcels of Ihumātao land – lots 13 and 14 – were bought by settler Gavin Struthers Wallace at an auction held by the Waste Lands Office. Wallace paid a combined sum of £658 for 81 acres, which became lots 175 and 176, respectively.

This sale – which was sealed as a Crown Grant on 28th December of 1867 – bears the signature of no less a figure that the Governor of the Colony and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Freemason Bro. George Grey. Ironically, Bro. Grey signed this land grant a month after he himself received notice of his recall as Governor of the colony to return to London.

Historian Vincent O’Malley who wrote The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, emphasizes that the Waikato War really started at Ihumātao – before the shooting commenced following General Duncan Cameron’s troops crossing New Zealand’s version of Rome’s Rubicon River – the Mangatawhiri River– an awa that Governor Bro. Grey knew demarcated Waikato Māori territory and that if crossed it was a ‘point of no return’ – without provoking war. When war preparations were completed a few days ahead of schedule, Governor Bro. Grey moved ahead with plans to confiscate Māori lands that were discussed at an executive meeting on June 23 1863.

Contested Lands – The 81 acre Oruarangi Block at Ihumātao

The 81 acres that Gavin Struthers Wallace bought in 1866 for £658 are now-highly contested ground – known as the Oruarangi Block – where several hundred supporters of the Save Our Unique Landscapes (SOUL) Campaign are occupying with tents, in a stand-off with the Neo-Colonial Crown’s Police Constabulary. Fletcher Building consortium bought the 81-acre paddocked property off the Gavin H Wallace Limited in March 2014 December 2016 for a sum of $19 million, according to a Fairfax News report, “Ihumātao protest: Former landowner the Wallace family speaks out against stand-off ”. Fletcher Building’s subsidiary Fletcher Residential plans to develop for residential housing next to the Puketaapapa volcano at the edge of the Otuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve – that the manu whenua of Ihumātao consider sacred. The land, which was transferred to Fletcher Residential Ltd in December 2016 with a new title – was designated a Special Housing Area (SHA) 62 in November 2013 under the powers of the Housing Accords and Special Housing Areas Act 2013, whiuch gained Royal Ascent on September 13th 2013 – amid an ongoing housing crisis.

A major shareholder of Gavin H Wallace Ltd, Ailsa Blackwell, said the Wallace company sold an adjacent 52 acres (21 hectares) block for just over a $1 million dollars to contribute to the 100 hectare Otuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve. Aisla Blackwell – who is the grand-daughter of Gavin Struthers Wallace – said the amount that the Manukau Council offered for the remaining contested block of 81 acres (32 hectares) was not enough.

Evidently, the Manukau Council – acting on behalf of the Auckland Council – offered about $5 million and then raised the offer to $6.5 million after the Environment Court case of 2012 – in Gavin H Wallace Limited won a judgement to have the existing rural land zoning re-designated as a ‘Future development zone’ which drew the land within the Auckland Metropolitan Urban Limits. This move cancelled a protective Notice of Requirement placed by the Manukau City Council over the Oruarangi Block as an interim move in preparation for designating the land as Public Open Space in proposed amendments to the Manukau District Plan.15

Methodist Machinations in a Masonic British Colony

In his 1966 book, Old Manukau, historian Tonson wrote “Good work was done at Ihumatao until, with the outbreak of war, in 1863, the settlement was broken up and became deserted.”

In his 1900 book, The History of Methodism in New Zealand, Reverend William Morley stated that after twenty years of Wesleyan Methodist Mission in the Manukau District, which had been established in 1845 – Scottish families such as the Wallaces had joined the congregration in Mangere.16 The addition of the Wallace family to the Methodist congregation is fascinating because Gavin Struthers Wallace purchased land at Ihumātao in mid-1866.

Even more ironically, Wesleyan Reverend Thomas Buddle, who emigrated from Bristol in September 1839 on the 130 ton schooner, Triton, became an employee and eventually partner of Whitaker & Russell. It was Reverend Buddle who wrote the first lengthy account of the Kingitanga, or Māori King ‘kingite’ movement, The Maori King Movement in New Zealand published in 1860, since he had tracked it development, knew who the key figures were and was fluent in te reo Māori.

After their stint in politics during the “stormy time” of the Waikato War in 1863-64, Freemason Bro. Whitaker and Wesleyan lay-preacher Russell busied themselves in land-speculating, gold mine investing, and legal-paper work. For example, on February 19th 1870, Whitaker & Russell processed the legal paperwork when Gavin Struthers Wallace mortgaged the Ihumātao land for a loan from James Farmer.

Māori of Neo-Colonial New Zealand today could be forgiven for thinking that the participation of the Wallace family in the Methodist Church in Mangere reflected a stealthy Methodist Connection method to acquire and grow a congregation through Māori land acquisitions. As indigenous scholars Professor Robert J Miller and Jacinta Ruru and many others have found, Christianity was one element of ten elements identified as part of a secret piece of international law known as the Doctrine of Discovery that was used by the European Maritime Empires to lay claim to territories inhabited by ‘savages’. Because ‘the Natives’ of the ‘New World’ were not Christians busy cutting vast swathes of forests for sheep and cattle to graze when such territories were ‘discovered’, they were deemed too ‘primitive’ to be considered ‘sovereign’ – and, therefore, were considered to lack full political rights.17 The deployment of Christian Missionaries worked as a ‘Great Softening’ mechanism to prepare indigenous peoples for being assimilated into the European Maritime Empires.

Untouched wildernesses throughout the British Masonic Empire were termed ‘Waste Lands’ by Crown officials, Protestant missionaries and land-hungry settlers. In the case of Ihumātao – as with elsewhere in the Tamaki Makaurau region, where 1.2 million acres of ‘Waste Lands’ were confiscated off ‘rebellious Natives’ and ‘friendly Maoris’, as the 1928 Sim Report found – such ‘waste lands’ also included villages, cultivated lands and coastal landings adjacent to beaches that Māori depended upon for access to kai-moana, or sea food.

For their part, the Wesleyan Methodists contributed to Māori land loss. This was ironic given that it was Methodist ministers who warned Māori at the Ihumātao Kingitanga hui in mid-1857 that if they persisted with electing a Māori king, the Pākehā settlers would tear them to pieces – as The Snoopman revealed in “Dispatch from Ihumātao #001 – The Kingitanga Connection”. It is also ironic that the Kingitanga hui at Ihumātao in mid-1857 morphed out a commemorative tangi for chief Te Rangitaahua Ngamuka and known as ‘Native’ Preacher Epiha Putini, who died in 1856. Reverend Buddle stated that this tangi was observed by Protestant Ministers and other ‘Gentlemen’ and recounted by Bro. John Gorst in his 1864 book, The Maori King. Yet, it was followed from afar by Government officials, whom stayed away – as Government historian Guy Scholefield makes clear in his two-volume time, The Richmond–Atkinson Papers published in 1960.

Did the Wesleyan Mission play a role in instigating this commemorative tangi with a view that it would morph into a ‘monster Maori gathering’ to discuss the Kingite movement’s kaupapa – as A. E. Tonson described te rangatira hui in his 1966 book, Old Manukau? A further question arises – to what extent did the Wesleyan Method Mission in the Manukau play Māori, including those connected to the institution of the Kingitanga – with a hidden agenda?

This investigation has found that almost immediately after the evictions of ‘Ihumatao natives’, some of the land was leased to Henry Vercoe, whose mother’s brother was Wesleyan Minister, Reverend Walter Lawry. Henry Vercoe was also the brother-in-law of Wesleyan lay preacher, Thomas Russell, who was “the leading spirit in the flotation of the Bank of New Zealand” – which brokered a £3 million loan from the Imperial Government to finance the escalation of the New Zealand Wars. Russell was also Minister of Colonial Defence during the Waikato War of 1863-64, serving with the Premiere of New Zealand, Freemason Bro. Frederick Whitaker (1863-64), with whom he owned a law firm called Whitaker & Russell. Furthermore, Wesleyan Reverend Thomas Buddle – who wrote the first full length report on the Kingitanga, titled, The Maori King Movement in New Zealand, published in 1860 – worked for the land-swindling, gold speculating, swamp-draining Whitaker & Russell law firm that was at the core of the Masonic takeover of Māori territories and eventually became a partner. Additionally, a settler farmer Gavin Struthers Wallace, who bought lots 175 and 176 of the confiscated Ihumātao land was of the Scotch Wallace family whom joined the Wesleyan Methodist congregation in Mangere in the mid-1860s. This Wallace family farm land, comprising 81 acres was sold to Fletcher Building Limited in late 2016 to develop as housing.

=====

Editor’s Note: Please let me know if I have made any errors.

e: steveedwards555@gmail.com

Deep History of Ihumātao: The Freemason Connection

The Masonic New Zealand Wars: Freemasonry as a Secret Mechanism of Imperial Conquest During the ‘Native Troubles’

Referenced Sources:

1 Reverend William Morley. (1900). The History of Methodism in New Zealand, p.104. Wellington, NZ: McKee & Co.; Reverend W. J. Williams. (1922). Centennial Sketches of N.Z. Methodism. Christchurch; NZ: Lyttelton Times.

2 South Auckland Research Centre. “The lost village of Pehiakura Collection”. Ref # MNP MS 222. Retrieved from http://thecommunityarchive.org.nz/node/284140/description

3 Clarence T. J. Luxton. “Methodist Beginning in the Manukau: The Story of Pehiakura Mission, 1834-1862.” Retrieved from http://www.methodist.org.nz/files/docs/wesley%20historical/17(4)%20methodist%20beginnings%20in%20the%20manukau%20.pdf

4 Vincent O’Malley. (2015): The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, p 83; See also: TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA HISTORY http://www.teakitai.com/index.php/history

5 Snoopman. (July 27, 2019). Deep History of Ihumātao: The Kingitanga Connection. Retrieved from https://snoopman.net.nz/2019/07/27/the-deep-history-of-ihumatao-the-kingitanga-connection/

6 Vincent O’Malley. (2015). The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, p. 206. Bridget Williams Books.

7 T. B. Byrne. (1991). Wing of the Manukau: Capt. Thomas Wing: His Life and Habour 1810-1888, p. 297-298. Auckland, New Zealand: T. B. Byrne.

8 Professor Harold Miller in his 1966 book, Race Conflict in New Zealand, 1814-1865, p. 220.

9 Guy H. Scholefield (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand, p. 265. Department of Internal Affairs; A. H. McLintock. (Ed.). (1966). An Encyclopedia of New New Zealand, Vol. 3, p. 158. Wellington, New Zealand: R.E. Owen.

10 Te Ara Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Story: Russell, Thomas. Retrieved from https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1r20/russell-thomas

11 McLintock (Ed.). (1966). An Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Vol. III, p.p. 158-159; 651-653.

12 James Belich. (1988). The New Zealand Wars: And the Victorian View of Racial Conflict; Danny Keenan. (2009). Wars without End: The Land Wars in Nineteenth-century New Zealand; Tony Simpson (1986). Te Riri Pakeha: The White Man’s Anger. Auckland, NZ: Hodder and Stoughton; Belich. (1988). The New Zealand Wars: And the Victorian View of Racial Conflict; Vincent O’Malley. (2015). The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000. Bridget Williams Books.; Dom Felice Vaggioli. (2000 [1896]). History of New Zealand and its Inhabitants, Vol. II. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press.

13 Anna (Lawry) Vercoe (bef. 1801 – 1862). Retrieved from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Lawry-273; Te Ara Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Story: Russell, Thomas. Retrieved from https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1r20/russell-thomas

14 Professor Harold Miller. (1966). Race Conflict in New Zealand, 1814-1865, p. 220; A Settler. (18 February 1864). The Ihumatao Lease. Page 5. New Zealander, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18640218.2.23? query=Ihumatao&start_date=18-02-1864&end_date=18-02-1864&snippet=true&title=NZ

15 Geoff Chapple. (3 June 2016). Ihumatao and the Otuataua Stonefields: A very

special area. *Noted and The Listener*. Retrieved from

16 Reverend William Morley. (1900). The History of Methodism in New Zealand, p.224[124].

17 Professor Robert J Miller. (March 30, 2012) The Doctrine of Discovery: The International Law of Colonialism, Lewis & Clark Law School. Indigenous Peoples Forum on the Impact of the Doctrine of Discovery. Retrieved from: http://doctrineofdiscoveryforum.blogspot.co.nz/2012/03/doctrine-of-discovery-international-law.html; “The Still Permeating Influence of the Doctrine of Discovery in Aotearoa/New Zealand: 1970s-2000s – Foreshore and Seabed”, p. 237-239. In: Robert J. Miller, Jacinta Ruru, Larissa Behrendt and Tracey Lindberg. Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies, p. 6-8. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; Robert J. Miller (2006). Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark Manifest destiny. p.10. Westport, Connecticut; USA: Praeger.