A land dispute five minutes drive from Auckland International Airport became a news story of national significance in July and August of 2019. The fight led by whenua protection group, SOUL, or Save Our Unique Landscapes, to stop a transnational construction company’s proposed housing development on historically significant land, has led to discussions around New Zealand about the ‘precedent’ a buyback of private land at Ihumātao might set for other lands confiscated off Māori.

This investigation explores the relatively few examples of land-buybacks, showing they are fraught with backlashes from Pākehā, which suits the self-preservation of the politely racist Pākehā Ruling Class, whom draw out the processes over many years to deter, frustrate and soften Māori, like butter, by leaving them sitting on the bench so they ‘go off’.

By The Snoopman, 24 September 2019 [Updated 27 Sept 2019]

Precedents for Private Land Buy-Backs by Council & Crown

At the centre of the land dispute at Ihumātao, in Mangere, is the delicate issue of whether any public and private institutions will stump-up the money so that the community of Ihumātao — whom are seeking the return of ancestral lands — can prevent the historically significant site from being bulldozed for a housing development.

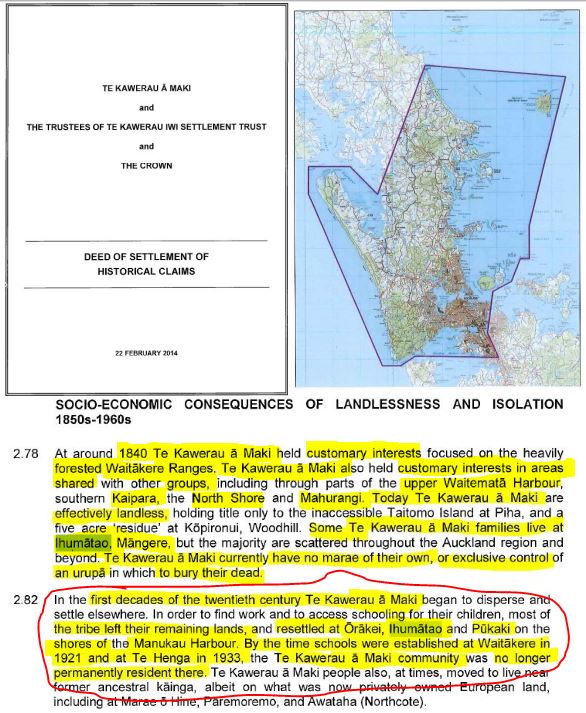

Many have added confusion to the dispute by asserting that there has already been a Treaty settlement for Ihumātao, such as former Treaty Negotiations Chris Finlayson who claimed he settled claims at Makaurau Marae, Ihumātao on 22 February 2014. But, this settlement was with the marae-less, land-less Te Kawerau ā Maki tribe and did not include the confiscations in the mid-1860s or anything about Ihumātao. Indeed, there hasn’t been a settlement for Ihumātao, as Dr Rawiri Taonui made emphatically clear in his article, Ihumātao | No Treaty Settlement opens three-way Solution on Waatea News. Despite the “Manukau Report of 1985”, which laid out a horrendous history of Pākehā incursions into the rohe of numerous hapū and iwi, the Manukau Region has not had a comprehensive Treaty settlement. Nor has the Crown, the Councils, and Courts gained permission, in many instances, from various tangata whenua to dispose, desecrate and develop upon their ancestral lands, wāhi tapu sites and waters – as reported in October 2015 by journalist Wena Harawira (who started out as a seventeen year-old under the wing of none other than multi-season One Network News anchor, Judy Bailey [1987-2003], of Pākehā-household-name-fame). Auckland’s incumbent Mayor Phil Goff has added to the confusion, by consulting Tainui-Waikato, Te Ākitai Waiohua and Te Kawerau ā Maki (Te Kawerau). As Dr Rawiri Taonui pointed out on Waatea News in a piece titled, Ihumātao | Auckland Council Fails to Front:

“This is one of the problems. Tainui-Waikato, Te Ākitai Waiohua and Te Kawerau have interests but are not the principal mana whenua group at Ihumātao. The historical record between 1835 and 1966, which pre-dates the current Treaty settlement era and hence is free of the mana gobbling that sometimes plagues iwi today, show an amalgam of Ngāti Te Ahiwaru and Ngāti Māhuta (Te Ahiwaru) were the principal iwi at Ihumātao. Te Ākitai Waiohua were mana whenua at Pūkaki. Te Kawerau were mana whenua in West Auckland.”

That there are few examples of public institutions purchasing lands off private owners is testimony to the racism endemic to New Zealand’s Pākehā Ruling Class. Two cases cited here – the Te Roroa-Titford case and the Te Kawerau ā Maki Marae site purchase at Te Henga – demonstrate begrudging reluctance, coercion, and yes, even stonewalling machinations.

The Te Roroa-Titford case sparked a racist backlash from the large segment of poorly educated Pākehā New Zealanders across all classes, and this backlash resulted in the Crown prohibiting itself from direct acquisitions of privately-owned land for return to Māori. The Te Kawerau ā Maki Marae case shows that the Waitakere Council and Auckland Council have together dragged out the process of finding, buying and transferring title of land for the tribe to build a marae and papakāianga in their ancestral heartland, the Waitakere Region, for 21 years.

Two further cases, the Mission Street property in Tauranga and the Te Atatu Marae project in West Auckland, are cited to show the real problem underpinning transfers of land is this: well-healed Pākehā can easily stir up poorly-educated, less well-off Pākehā to oppose Māori being resourced – even on a small scale. Because in the Mission Street case in Tauranga, well-off Pākehā were perfectly happy for the Tauranga City Council to buy them a property adjoining the historic Church Missionary Society Mission House, known as ‘The Elms’. In case of the Te Atatu Marae project some Pākehā objected to a straight gift to Māori of land in a park that the Waitakere City Council owned. Pākehā claimed the aesthetics of structures would spoil the views of the Waitemata Harbour, while seven Pākehā families sued the Waitakere City for the return of the land bought from them in 1958 under the Public Works Act.

First, let’s look at the case that led to the Crown placing an embargo on private land buy-backs for Māori in Treaty Settlement claims.

Te Roroa Iwi-Titford Farm Battle

The intriguing Te Roroa-Titford battle in the late 1980s to 1995 offers an exquisite example of a Northland farmer and assorted associates sabotaging the precedent of land buy-backs off private owners by the Crown.

A Northland iwi, Te Roroa, sought the return of urupa, burial caves and other wāhi tapu sites on farmed lands at the Maunganui Bluff, Aranga, north-west of Dargaville. Te Roroa iwi had claimed 38ha of the 688 hectare property, bought by farmer Allan Titford in 1986 for $600,000, after it was found a Manu whetai Reserve, at the centre of the dispute, had been included in the farm land title. On March 1st 1992, the Waitangi Tribunal recommended that the Aranga farm be returned the Te Roroa iwi. In 1995, the Crown paid $3.25 million – after a bitter dispute – and after Titford’s house was razed to the ground just before midnight on July 4th 1992 and not before the farmer bulldozed a preserved pa. The arson helped inflame anti-Māori sentiment across the country, Pākehā resentment about Treaty claims and emboldened lobbying to take private lands ‘off the table’ in Treaty Settlements.

By his own admission in a 1998 book, Robbery by Deceit, Titford claimed his house was billowing with smoke when he arrived home from a dinner, and the fire spread fast as he opened doors.

In 2013, when Titford was convicted of arson – among other crimes – Judge Duncan Harvey said, “it [was] time for the people of New Zealand to learn the truth” because his devious and malicious actions were designed to turned the public against Māori and garner sympathy for himself so that he would get higher compensation from the Crown for his farm.

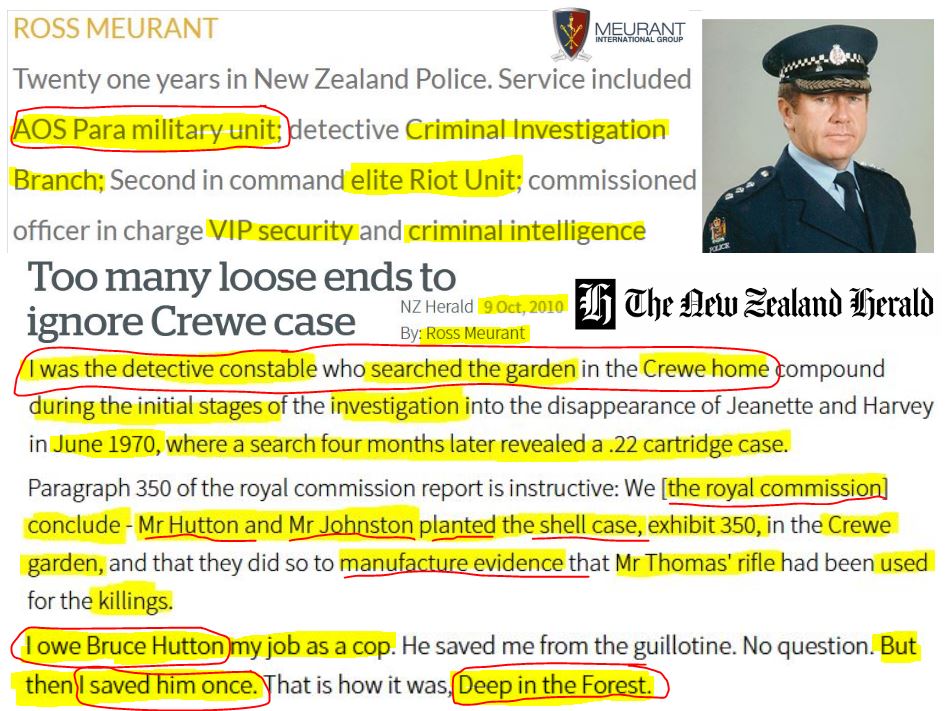

This mission for sympathy was helped along when Titford rang local National Party MP Ross Meurant, whose first thought was to ring The New Zealand Herald. This Herald call was strange because according to Titford, Meurant had said a few years prior there was nothing more he could do to help Titford because it would effect his political career. Meurant’s role could qualify for entry into a spooky file. He was formerly second in command of the Red Escort Group, or Red Squad, during the 1981 Springbok Tour, back when the Muldoon-National Government was in power and the South African Apartheid Regime was controlled by the Afrikaner Broederbond, a white supremacist brotherhood modelled on British Freemasonry. The deep purpose of the Old Pākehā Boys’ Network – wearing the cloak of the New Zealand Rugby Union to host the Tour – was to divide the country into two broad social cohorts: anti-intellectuals and free-thinkers. The encoded meaning embedded in the mantra — ‘politics and sport should not be mixed’ — was that the racist Realm of New Zealand would be re-conquered using the secular national religion, rugby, to re-open up the racial-cultural fault-line. The act of hosting the South African rugby team had been identified as a flashpoint for civil unrest on the streets of New Zealand in a 1978 book of essays, Thirteen Facets: The Silver Jubilee Essays surveying the New Elizabethan Age, a Period of Unprecedented Change. Rugby fans repeated the mantra ‘politics and sport should not be mixed’ to justify their racism without realising that a half-hour of sports coverage in the six o’clock news was consistent with the British Empire spreading rugby and cricket in the colonial era as a form of soft power to distract, brainwash and bend the freewill of ‘the subjects’ into loyalty for Royalty.

whose first thought was to ring The New Zealand Herald, which is suspicious since he was formerly second in command of the Red Escort Group, or Red Squad, during the 1981 Springbok Tour, in which a good deal of Māori got bashed with Police truncheons.

As The Spinoff recently reported, Titford’s racist campaign (which included the arson) – “the (Bolger) National government relented and changed the legislation to exclude the return of private land to iwi.” It is therefore intriguing that National MP Ross Meurant phoned The New Zealand Herald straight after Titford rang him, instead of using his detective skills to see if Titford was framing Te Roroa. Meurant’s formative years working in close proximity to the ‘Deep in the Forest police subculture’ such as on the Crewe Murder case in which the Police planted a .22 calibre shell in the Crewe house garden to frame Arthur Allan Thomas – perhaps had a long-term impact on the young detective constable. He admits in an October 2010 The New Zealand Herald article “Too many loose ends to ignore Crewe case” that he saved Detective Inspector Bruce Hutton, since Meurant kept quiet even after a Royal Commission concluded that Mr Hutton and Detective Sergeant Len Johnson planted the ICI-manufactured shell case in the garden. Meurant also admitted he had personally searched the farmhouse garden and that in a repeated ‘search’ four months later, the .22 cartridge shell was ‘found’, but he says he did not plant the shell. Therefore, because Meurant had participated in furtherance of conspiracy to frame Thomas – because by his own admission he had kept quiet – he was actually an un-convicted criminal at the time that he also failed as a Member of Parliament to investigate Titford’s machinations. Instead, he aided those machinations. To the ‘Deep in the Forest Police subculture’ who knew the Hobson electorate MP’s past of keeping secrets about the Crewe Murder Case planted-evidence, they would have seen the fix was in and sensed perhaps there was a Deep State operation to set the boundaries of Treaty Settlements).

Indeed, the impacts on Te Roroa iwi were long-term. In 2011, Te Roroa were still seeking the return of 2000 hectares of ancestral lands, which included wāhi tapu burial lands, Kaharau and Te Taraire, at Waimamaku and seeking more cash from the Crown because Māori face the hurdle of paying market prices to purchase private lands. On 23 October 2011, before the Parliament’s Māori Affairs Select Committee hearing Rev. Daniel Ambler refuted the position that Te Roroa should pay for burial grounds confiscated by the Crown. Speaking to Dave Hereora (chairman), Georgina te Heuheu, Pita Sharples, Pita Paraone, Chris Finlayson, Tau Henare, Mita Ririnui and Charles Chauvel – Reverend Ambler said it was a mockery and cultural insult, adding:

“We never sold Kaharau. The caves were raped of everything in them and now they want us to buy those places back.”

The racist furore stirred up by Titford and his farming supporters resulted in the Bolger-National Government barring the Waitangi Tribunal from recommending such sacrilegious property transfers and thereby making discourse about private-land buy-backs a heretical act in the racist Realm of New Zealand.

Next, we examine the polite racism, collusion and stonewalling to frustrate, deter and soften Te Kawerau ā Maki iwi in its multi-year efforts to regain some land at Te Henga for a marae and papakāianga housing.

Te Henga/Bethells Beach Marae Site

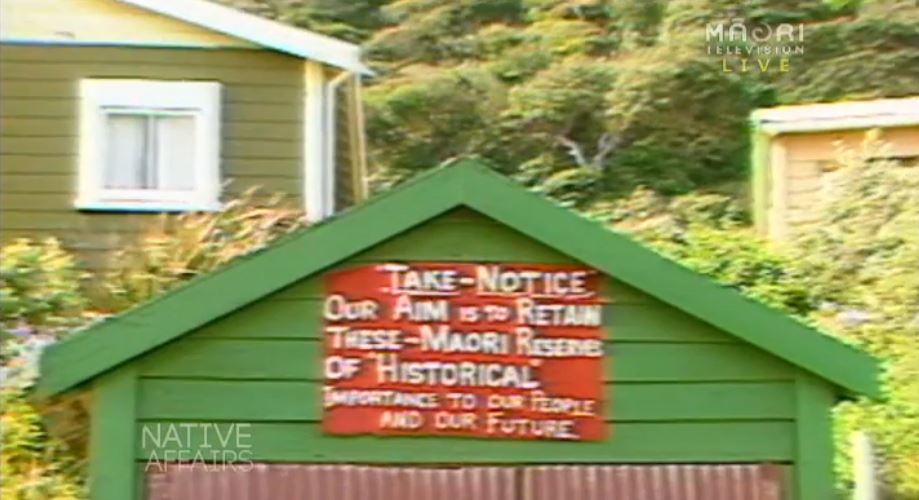

A land buy-back at Te Henga/Bethells Beach by the Waitākere City Council for the once-were-landless Te Kawerau ā Maki iwi to build a marae, reveals a horrendous process drawn out over 21 years. The Waitākere City Council entered a memorandum of understanding agreement with Te Kawerau ā Maki in 1998 which stated the Council would find and buy a suitable site for the tribe to build a marae and papakāinga housing in one of their ancestral strongholds. Te Kawerau ā Maki stated at the time its preference that the land title be transferred to the iwi, rather than a lease arrangement.

In 2009, the Waitākare Council bought a 2.7 hectare site at Te Henga/Bethells Beach for ‘community development purposes’ with the intention that the property would be leased to Te Kawerau ā Maki so that the iwi could build a marae. The iwi held firm to their preference not to lease the land, which the Waitākere Council bought for $935,000. Numerous Pākehā residents practiced polite racism when they complained that the council did not allow them to build cabins and ablution blocks to service summer caravans on private property and annoyance at public money being used without public consultation.

In an April 13 2010 news report, Land buy for Marae, a Bethells resident Barry Browne questioned why property taxpayers should pay for the land purchase when a tribal Treaty settlement was in the works.

“There is no point asking for submissions, or opening community discussions after the land has been purchased with our money. This tribe already has use of a marae in Mangere,” Browne moaned.

However, Pākehā numerous resident’s supported land at Te Henga being gifted to the tribe rather than leased. For instance, Vanessa Cameron-Lewis told The Aucklander:

“If this land is leased to Te Kawerau a Maki, but ownership and thus control is not gifted to them, then this proposal would do nothing but create – and arguably continue – a paternalistic, colonial relationship between council and iwi.”

The game to draw Te Kawerau ā Maki into a long-winded process can be seen in the following sequence of screen collages from various council reports, news stories and committee minutes.

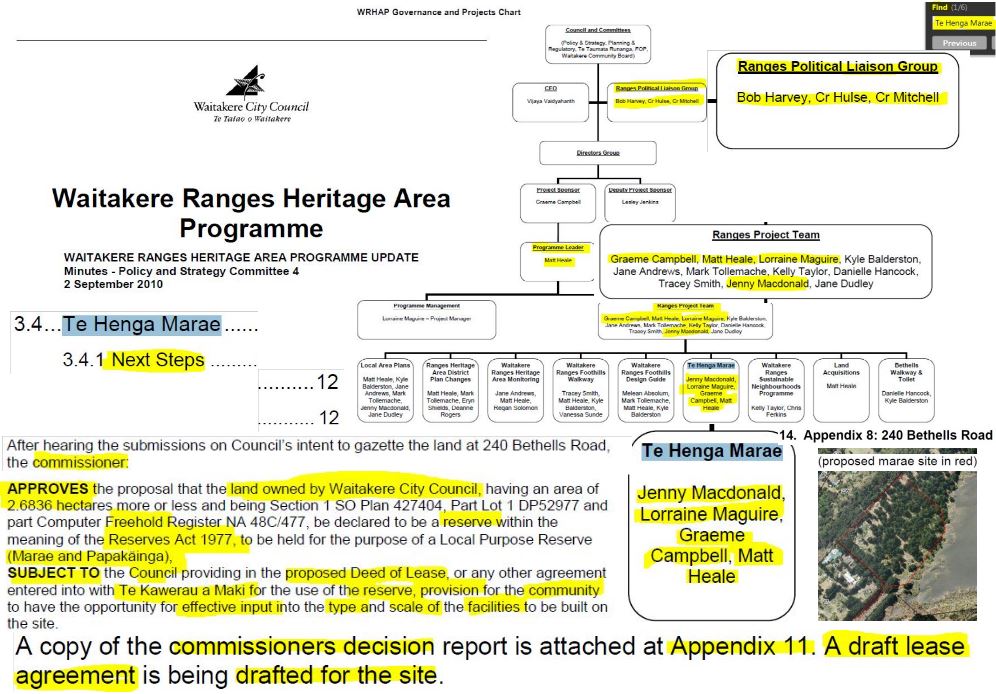

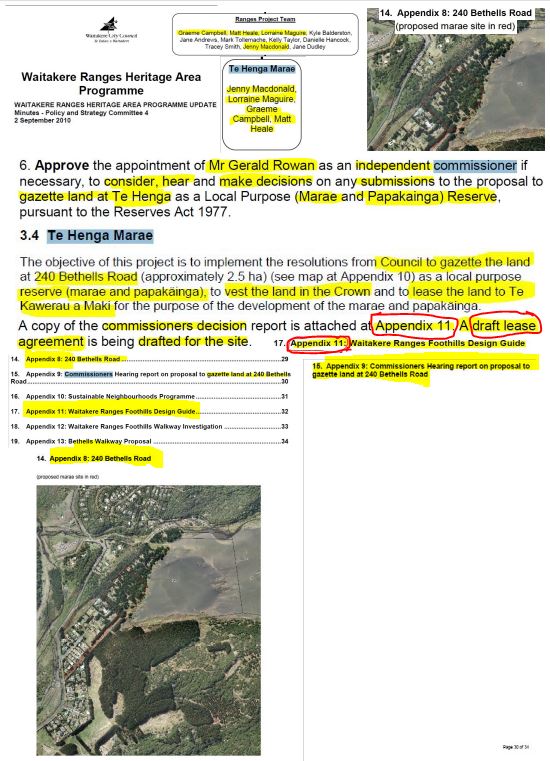

On 2 September 2010, the Auckland Council’s Policy and Strategy Committee approved the Waitakere City Council’s proposal vest the land in the Crown, and to appoint a commissioner who would evidentally draft a lease agreement and consider, hear and make decisions on submissions.

In its undated update report, “Waitakere Ranges Heritage Area Programme Minutes,” on the Auckland Council’s Policy and Strategy Committee meeting of September 2 2010, it stated that a copy of the commissioner’s decision report was attached in Appendix 11. However, Appendix 9 which was titled, “Commissioners Hearing report on proposal to gazette land at 240 Bethells Road” is blank. The report also noted that a lease was being drafted for the proposed marae site. The actual Appendix 11, titled “Waitakere Ranges Foothills Design Guide” was evidently about future building and subdivision in the Waitakere Ranges Foothills of the Waitakere Ranges. But, it is hard to tell if that was the case, because this appendix was also blank, along with almost every other appendice, except “Appendix 8: 240 Bethells Road”, showing the proposed marae site on a map (and also another appendice showing a Local Area Plan process chart for Oratia).

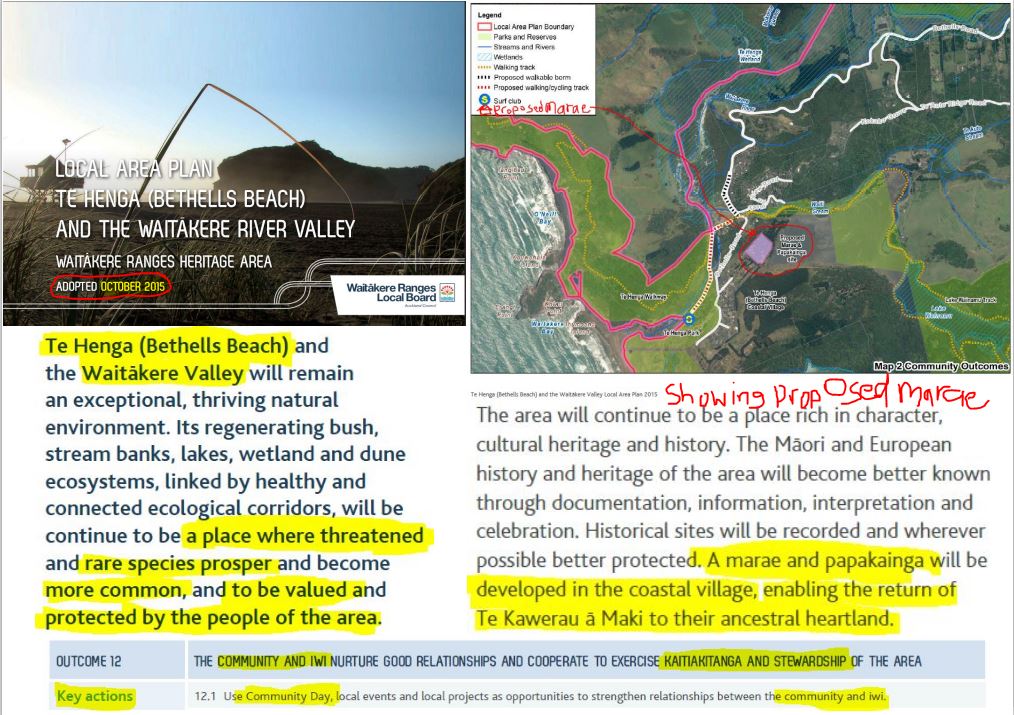

In this way, Te Kawerau ā Maki were drawn into a long-winded process which included the appointment on September 2nd 2010 of an independent commissioner, Mr Gerald Rowan. He was evidently going to draft a lease agreement for land that the Auckland Council resolved to vest in the Crown, in spite of the tribe expressing to the Waitākere City Council in 1998 that it wanted the land to be vested in the iwi. Ironically, in an October 2015 report, “Local Area Plan Te Henga (Bethells Beach) and the Waitākere River Valley”, the Waitākere Ranges Local Board stated the territory will remain an exceptional … place where threatened and rare species … become protected by the people of the area.” Meanwhile, residents were informed that “[a] marae and papakainga will be developed in the coastal village, enabling the return of Te Kawerau ā Maki to their ancestral heartland.” One outcome for the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area was for “Key Actions” to occur, such as “community day” to strengthen relationships between the community and iwi so that together they could exercise kaitiakitanga and stewardship.

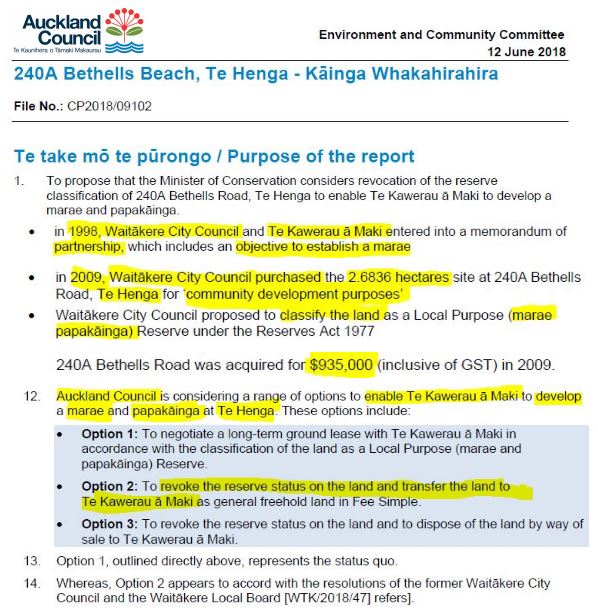

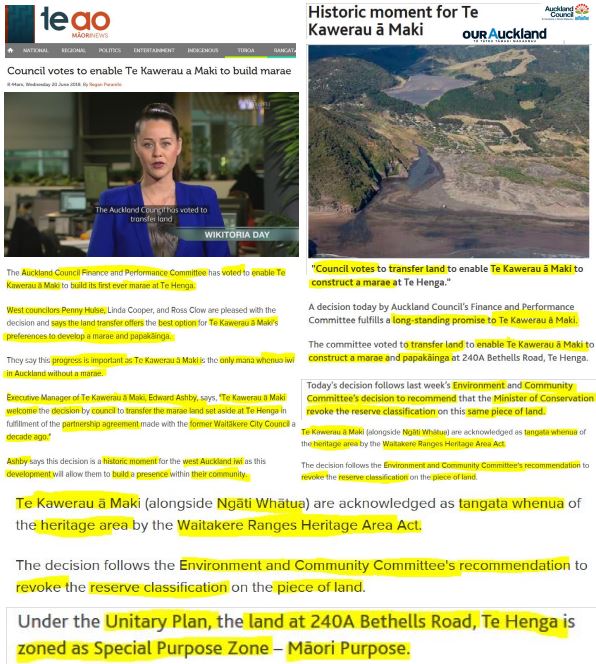

But, nearly three snail-pace years later – in June 2018 – the Auckland Council’s Environment and Community Committee prepared a report for the Auckland Council’s Finance and Performance Committee to vote to gift Te Kawerau ā Maki the land at 240a Bethells Rd, Te Henga, to build a marae and papakāinga housing. The Environment and Community Committee’s report of June 12th 2018 shows that “option 2” – to transfer Te Kawerau ā Maki appeared to be in accord with the former Waitākere City Council and Waitākere Local Board. However, the Environment and Community Committee noted that option 1 – to negotiate a land lease with the iwi was the status quo.

On 13 June 2018, Waatea News reported that Te Kawerau ā Maki was a step closer to building a marae and papakāinga in its “ancestral heartland territory” at Te Henga. The Waatea News report “Council paves way for Te Kawerau a Maki marae” gazetted that the tribe and the Waitakere City Council identified Te Henga as the preferred marae site in 1995. Moreover, Waatea News reported that Te Kawerau ā Maki rejected the Council’s tabled option to lease the land to the iwi when the local government authority bought the site in 2009. The Auckland Council’s Environment and Community Committee moved to ask the then-Minister of Conservation, Eugenie Sage, to revoke the reserve classification, and to recommend that the Auckland Council’s Finance and Performance Committee transfer title of the land to the tribe.

On 19 June 2018, in a Fairfax Media’s Stuff article – “Te Henga marae will be ‘the heart’ of Te Kawerau ā Maki” – a West Auckland Wards Councillor, Penny Hulse, was reported to have said in December 2017, “We will resolve the Te Henga marae issue”. When Hulse made this promise at an Auckland Council Environment committee meeting, she added, “It’s untenable that it has taken this long, and for that I apologise.”

Fascinatingly, in the same Stuff story, Te Kawerau ā Maki Iwi Authority chief executive Edward Ashby said in a public relations statement,

“A marae is four walls but it’s also the people that support the marae that’s important. This is essentially the very heart of Te Kawerau ā Maki so we want to do it once and we want to do it well.”

Very Heart of Te Kawerau ā Maki: Iwi Authority chief executive Edward Ashby knows very well that numerous remaining members of the iwi living Te Henga left in the 1960s.

In other words, Ashby was really saying – the Makaurau Marae at Ihumātao Village in the District of Mangere was not really the ancestral marae of Te Kawerau ā Maki, as some Pākekā may have thought when seeing in the news about the Ihumātao land dispute. The tribe’s deep ties are in the Waitakere Ranges, its foothills and valleys and the rivers, as well as the West Coast by the Waitakere Forest – as the iwi’s signed Deed of Settlement with the Crown on February 22 2014 attests its linkages reach back to the 1600s. Indeed, the Makaurau Marae of Ihumātao village is located on the Ihumātao Peninsula, itself located on the eastern shores of the Manukau Harbour. The confusion arises, in part, from the fact that the marae-less tribe signed their Deed of Settlement at Makaurau Marae in Ihumātao, partly because the tribe’s mandated negotiator, Te Warena Taua, had lived in the village since he was an infant. And partly because Makaurau Marae was used as a signing location because it was close to one of the very things that had taken so much from one of their ancestral taonga, Maungataketake, which was quarried to build the runways of the Auckland International Airport. And partly because numerous remaining members of the iwi living at Te Henga left in 1912 following the death of their chief Te Ūtika Te Aroha, and moved to be with relatives in Ōrākei and Pūkaki and Puketāpapa (Ihumātao) – as the Waitākere Ranges Local Board states in its October 2015 report, “Local Area Plan Te Henga (Bethells Beach) and the Waitākere River Valley”. This brief history was evidently supplied by Te Kawerau Iwi Tribal Authority in May 2014.

Fascinatingly, the website of Te Kawerau ā Maki, which is owned by Te Kawerau Iwi Settlement Trust & Tribal Authority makes no claim about the tribe being mana whenua or tangata whenua of the Puketāpapa locality within Ihumātao, where Pania Newton has led the occupation since 2015. Instead, the tribes website states:

“Te Kawerau a Maki are the tangata whenua (people of the land) of Waitakere City, who hold customary authority or manawhenua within the city. Te Kawerau a Maki descend from the earliest inhabitants of the area. However, the Kawerau a Maki people have been a distinct tribal entity since the early 1600s, when their ancestor Maki and his people conquered and settled the district.”

The website brief history finishes, explanation of why the remaining members of the iwi left the Waitakeres in 1912 and Te Henga in the 1960s. However, Te Kawerau ā Maki’s website censors its own brief history by neglecting to mention that some of its people went to live at Puketāpapa, Ihumātao in 1912. This is a curious omission given that Te Kawerau ā Maki’s most prominent mandated kaumātua, Te Warena Taua, has frequently claimed that he represents the mana whenua of Ihumātao and he has also actively misled people into believing that his tribe is the local iwi, as The Snoopman showed in his exposé, “Te Warena Taua – The mandated kaumātua who authored his own use-by-date?”

“Te Kawerau a Maki remained primarily in the Waitakere River and Piha areas, and maintained the only papatipu settlements in the West. However, following the death of their chief Te Utika Te Aroha in 1912 most of those remaining moved to the settlements of their close relatives at Orakei and Pukaki. They still retained land at Te Henga and returned intermittently to occupy it until the 1960s, by which time the reserved land had been sold as a result of the individualisation of land titles introduced by the Native Land Act, and economic pressures. No other iwi occupied West Auckland at any time during this period. Over the last 150 years Te Kawerau a Maki have alone kept their fires burning in West Auckland. They have retained ahi ka roa and manawhenua.”

This censorship becomes more galling when The Snoopman finds that in Te Kawerau ā Maki’s Deed of Settlement document, dated February 22nd 2014, the tribe’s own historical account states that in the first decades of the 20th Century “most of the tribe left their remaining lands, and resettled at Ōrākei, Ihumātao and Pūkaki on the shores of the Manukau Harbour”.

Ironically, given the fight at Ihumātao, the Auckland Council’s online news site Our Auckland gazetted on 29 June 2018 that “the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area Act acknowledges Te Kawerau ā Maki (alongside Ngāti Whātua) as tangata whenua of the heritage area”. The website also noted that “Under the Unitary Plan, the land at 240A Bethells Road, Te Henga is zoned as Special Purpose Zone – Māori Purpose.” The same could not be said for the disputed land at Ihumātao.

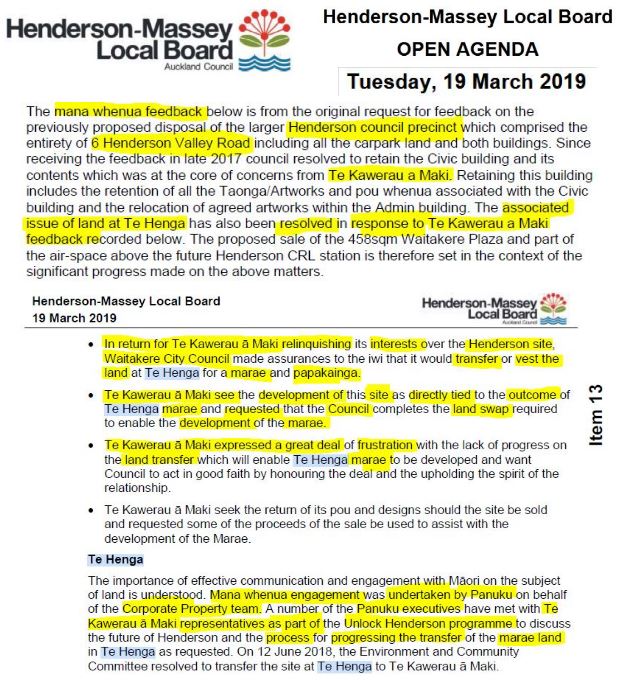

In spite of countless promises, votes and paperwork indicating that the Bethells Road land would be transferred to Te Kawerau ā Maki, including the much-hyped mid-winter meetings of June 2018, the Auckland ‘Old Boys Network’ Council held out. The Henderson-Massey Local Board minutes of March 19th 2019 show that a bargain was struck with Te Kawerau ā Maki to relinquish its interests in the precinct property on Henderson Valley Road, before the Council would transfer the title of the Te Henga property. The tribe expressed concern about the planned disposal of the Henderson Council Precinct property for further build-out of a transport hub by the Auckland Council’s development corporation that goes by the culturally correct name, Panuku. The bone of contention for Te Kawerau ā Maki was the retention of all the Taonga/Artworks and pou whenua associated with the Civic building and the relocation of agreed artworks within the Administration building. Evidently, Waitakere City Council advised Te Kawerau ā Maki it would not sell the land, and if it did Te Kawerau ā Maki’s pou would be returned. Panuku’s Corporate Team confirmed the Civic Building would be retained.

Pound of Native Flesh: This Henderson-Massey Local Board report shows that the Auckland Council withheld transferring the title of the 2.7 ha Te Henga/Bethells Beach property until Te Kawerau ā Maki withdrew its claim to the Council precinct on Henderson Valley Rd.

Agenda item 13 stated:

“In return for Te Kawerau ā Maki relinquishing its interests over the Henderson site, Waitakere City Council made assurances to the iwi that it would transfer or vest the land at Te Henga for a marae and papakainga. Te Kawerau ā Maki see the development of this site as directly tied to the outcome of Te Henga marae and requested that the Council completes the land swap required to enable the development of the marae. Te Kawerau ā Maki expressed a great deal of frustration with the lack of progress on the land transfer which will enable Te Henga marae to be developed and want Council to act in good faith by honouring the deal and the upholding the spirit of the relationship.”

The delays in transferring the land for a marae and papakāinga at Te Henga belie coercion by the Auckland Council and Waitakere City, especially since Te Kawerau ā Maki had been formally seeking a marae site since 1998 or 1995, depending on who’s count you take. The apparent plans to scuttle or re-purpose Waitakere City Council’s Henderson Civic Building looks more like a strategic concession, which is a political stratagem used to game your opponent by proposing something worse than intended. The ruse of a strategic concession is to appear to concede some ground while wasting a political rivals’ resources, time and attention and manipulating them into an agreement through ‘softening’. Hosting a Dial-a-Powhiri works to stroke the egos of the Ruling Class Pākehā psychic-vampires who run this shitty Neo-Colonial Realm, and whom get off on successfully playing ‘the Natives’ yet again, with the catharsis of the indigenous cultural ceremony.

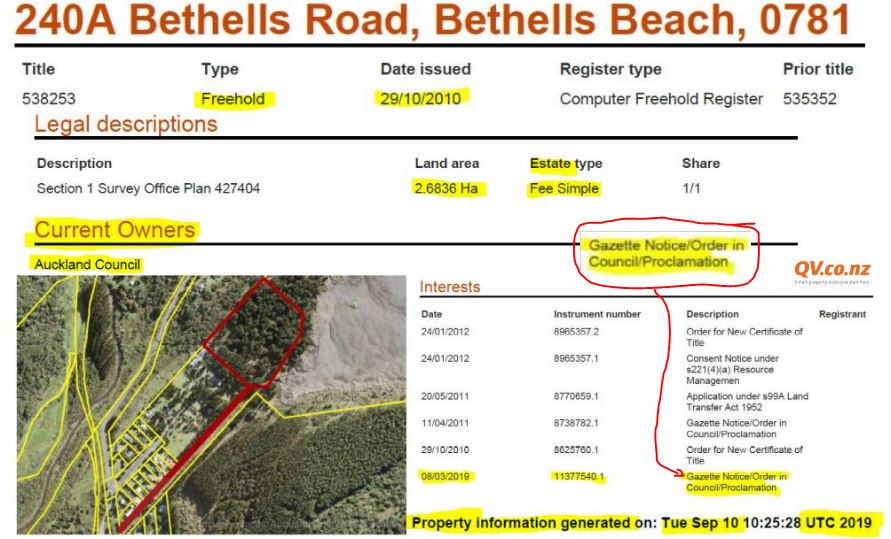

As of September 10 2019, it appeared that Auckland Council still held title to the proposed marae site at Te Henga, according to the QV property website. The metadata in the entry for March 8th 2019 showed that three mechanisms exist for the transferrance of land to Māori: either a Gazette Notice, an Order in Council, or a Proclamation.

Next, we review the case of a suburban property in Tauranga that the City Council recently voted to gift to a Māori trust, which would mean the historic Pākehā-controlled mission house located next door would have ‘the Maoris’ as neighbours.

Mission Street Tauranga Land Transfer

In the Mission Street case, the Tauranga Council has had to contend with a ‘harrowing’ racist backlash stirred up in a dispute over a property adjoining the historic Church Missionary Society Mission House, known as The Elms. The Ōtamataha Trust, which represents hapu Ngāti Tapu and Ngāi Tamarawaho, sought return of the title, because their ancestors had granted land use rights on a conditional basis to the Church Missionary Society in 1838.

On December 19 2018, the Tauranga City Council agreed in principle to transfer the 11 Mission St property to the Ōtamataha Trust for no cost, on the understanding the trust would lease the land to the Elms Foundation at a “peppercorn” rent such as $1 a year. In 2006, the Council purchased the 11 Mission St property for the expected future development of the neighbouring Elms site, one of New Zealand’s oldest heritage sites. The Elms Foundation leased the land from the council and in 2011 requested ownership of the property be transferred to it for free. The foundation planned to develop the property as a reception and education centre for the Elms with facilities to maintain and display its heritage collection.

The Ōtamataha Trust, which represents the interests of Ngāi Tamarāwaho and Ngati Tapu, also put in a claim to be gifted the land in recognition of their mana whenua status and ancestral connection, subject to a lease favouring the foundation. The counter-claim made by Ōtamataha Trust, sparked concerns from some councillors that the transfer would create a precedent for public land on the Te Papa peninsula – from Gate Pā north – to be given back to its original iwi owners. The Anglican Church’s formal apology to Tauranga Moana iwi in December 2018 over land deals with the Crown 151 years ago raised fears among Pākehā, since the historical laundry of the Protestant’s leading church was shown to be mucky.

In an interview with TVNZ‘s Marae current affairs programme, Mayoral candidate Margaret Murray-Benge – who is also partner of former Reserve Bank Governor, Don Brash – claimed people were not opposing the Council gifting the land to Ōtamataha Trust because it is a Māori group.

“If you just don’t give away ratepayers-funded land, paid for by ratepayers, to an outside body. You just don’t do it, regards of who the body is. So, it’s not a racial thing, it’s just really common sense tells me that’s not how local government should perform.”

Marae reporter Hikurangi Jackson spoke to singer-songwriter, Ria Hall, who said Tauranga is very much an Old Pākehā Boys’ Club. As she spoke, samples of the racist submissions opposed to the Council gifting the 11 Mission Street property to the Ōtamataha Trust were displayed in graphics.

Hall read the submissions opposed to the Ōtamataha Trust gaining ownership of the 11 Mission Street property next to the Elms at 15 Mission St. She said:

“Some of the submissions were just horrific. Shocking to read. Alarming to read. Perpetuating that we (Māori) are thieves, burglars, rapists ecetera, ecetera … I mean what is that? It’s hurtful. It’s extremely hurtful to think that people continue to believe those stereotypes.”

The racist responses in the submissions were not surprising to Deputy Chair of Ōtamataha Trust, Peri Kohu. He said:

“We’re having to deal with it all the time. Look at those submissions. No doubt, there are, dare I say it, old old people (Pākehā) who can’t live in Tauranga and not know be aware of that. But life goes on. The monocultural society in which they live is eroding.”

Commendable leadership was shown by Tauranga City Council’s chief executive Marty Grenfell, who asked historian Dr Vincent O’Malley to review the claims for accuracy, relevance and appropriateness. Grenfell asked O’Malley to investigate the land’s history because he said the backlash from Pākehā whom were opposed to ‘the Maoris’ getting the land back instead, had been “harrowing” for the Council’s staff. O’Malley – who wrote an epic tome, The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000 – presented his report to the Tauranga City Council on September 10th 2019. The historian found that the Church Missionary Society’s claim that the land at 11 Mission St was bought fairly and squarely purchased from Māori “does not withstand serious scrutiny”. The historian said it was a “conditional transaction” rather than an outright sale, and that the Church Missionary Society held the land in an implied trust for the benefit of Māori. Subsequently, the Crown gained the title through coercion and its loss was a “significant blow for local hapū”, O’Malley wrote. The Tauranga City Council received complaints that O’malley was biased agianst the Colonial Government.

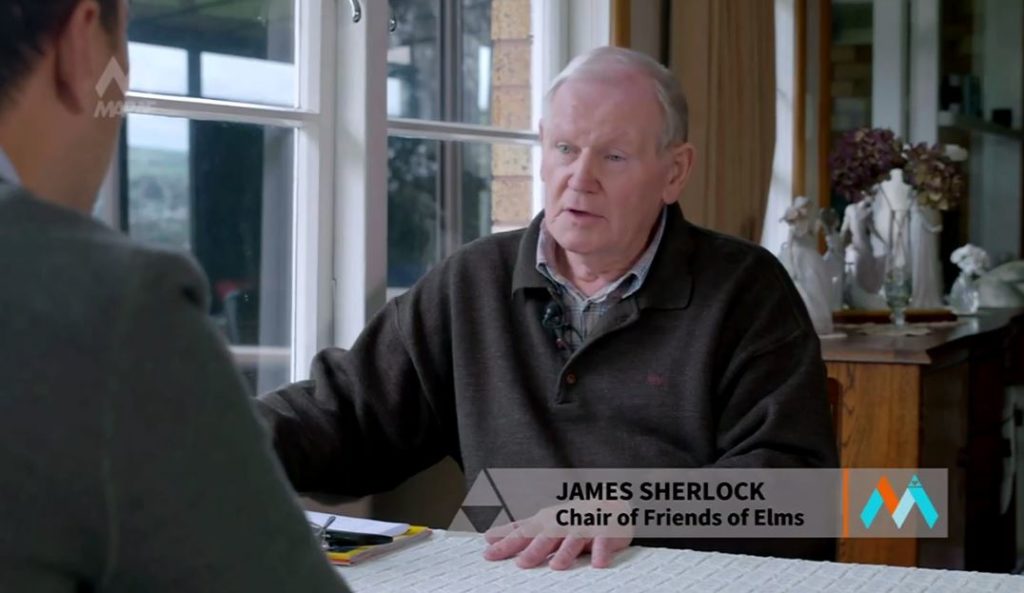

‘Friends of the Elms’ James Sherlock told Hikurangi Jackson that Reverend Brown bought the 1066-acre ‘Te Papa Block’ fair and square with 20 blankets, 10 axes, 10 spades, and 10 iron pots in 1838. At his Tauranga home, Sherlock referred to a book called Brown and the Elms by a local Pākehā historian who said Reverend Brown’s deed of sale was in English and in Māori and was signed by 17 rangatira. Deputy Chair of Ōtamataha Trust, Peri Kohu, says the land was not owned by Rev. Albert Nesbitt Brown because it had a caveat on the land that it must be kept in trust for Māori.

On September 10 2019, the Tauranga City Council voted 6 to 5 to gift the land at 11 Mission St to Ōtamataha Trust, on the condition that The Elms Foundation endorses the move, and the lease favours The Elms Foundation. However, when The Elms Foundation ‘agreed’ for the land to go the Ōtamataha Trust representing the two hapū, the Tauranga Council magically voted on September 24 for the land go to a trust representing both The Elms Foundation and the Ōtamataha Trust. Given that local body elections are looming, the issue has in effect been turned into an election policy platform for several councillors including the incumbent Mayor of Tauranga, reported Waatea News.

The fraught nature of transfers of land for Māori, is not limited to private land buy-backs of private land intended for Pākehā, and then counter-claimed by the ancestors of hapū, or iwi, who once held the land collectively. On the Te Atatū Peninsula on West Auckland, a proposed Marae Project on parkland owned by the Waitakere City Council was delayed for over a decade due a Pākehā backlash.

Te Atatū Marae Land Transfer

In February 2002, the Waitakere Council resolved to gift land for a marae and in July 2003 agreed to create a Māori reservation at Harbourview-Orangihina Park, on Te Atatū Peninsula. The Mayor at the time, Bob Harvey, wanted the park to become a cultural, art and tourism attraction, with a marae that would be partly sunk into a natural mound with a turf roof. The marae would be a facility to meet the needs of the broader community, as well as cater for the growing number of Māori youth in the suburb.

However, the Te Atatū Residents and Ratepayers Association led an oppositional campaign, as The New Zealand Herald reported on December 2nd 2003, in an article “Waitakere residents rally to block marae”. On February 29 2004, the Ratepayers Association filed an appeal to the Waitakere City Council’s decision, which was heard in December 2005. In a 2007 Environment Court case, the Te Atatū Residents and Ratepayers Association lost their argument that the land for the proposed marae was reserved as open space.

Next, seven Pākehā families fought the Waitakere City Council arguing that the entire park should be sold back to them, because the land was bought in 1958 under the Public Works Act for a port by the Auckland Harbour Board whom scuttled the project. They said the Waitakere City Council ignored its obligation under Section 40 of the Public Works Act to offer the land back to its original owners, as The Aucklander reported in “New marae for Te Atatu” on March 28 2007. The seven Pākehā families lost in the High Court, and again in the Court of Appeal on October 9 2015, and their application to appeal further to the Supreme Court was dismissed in March 2016.

In a February 2017 Stuff article, “Let us build this Auckland marae: Maori” – Michael Coote of Friends of Harbourview said his group opposed any development of the Auckland Council park. Mr Coote, who ran for the lkocal board on a singl mandate to oppose the Marae, was reported to have said if there is to be a marae, then the land should be leased to Māori, and not gifted.

“Why should ratepayers gift land worth millions of dollars to a marae complex that is subject to a risky commercial tourism venture for its continued existence?” Mr Coote moaned.

While Waitakere Councillor Penny Hulse said,

“There’s precedent for this. This is how Hoani Waititi Marae was set up. The council gifted by way of a long term lease land that was Parrs Park,” she said. “We need to have a look at what a long term lease might mean. What the marae committee want, quite rightly … is security of tenure so they can apply for funding.”

In a Stuff article of October 10th 2017, “Planning works underway for proposed west Auckland marae”, Te Atatū Marae Coalition chairman David Tanenui said he hoped to finalise the signing of the land agreement by June 2018, before Matariki Day. It could be said that the Waitakere Council,’s efforts with the Te Atatū Marae Coalition to progress the project was hampered by a Pākehā backlash. However, when viewed as a paired example with the Te Henga Marae project, a lack of leadership by the Waitakere Council to front-foot the issue of intransigent racism against Māori is blindingly obvious and belies subtle complicity to stonewall the marae project by maintaining a contrived ignorance about the Council’s own capacity call-out racism.

‘Tangata Whenua’: Land Required to Complete the Descriptor

Key Finding: The permanent embargo blocking the Waitangi Tribunal from recommending private land buybacks was, in no small part, the result of farmer Allan Titford burning his own house down in 1992. The Crown, Councils and Courts continue to practice contrived ignorance about the racism they are complicit in maintaining, as matter of self-preservation. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s politely racist Pākehā Ruling Class maliciously play Māori in drawn-out processes in the few existing cases of land transfers. Such stonewalling extends to maintaining a contrived ignorance about where exactly Te Kawerau ā Maki holds tangata whenua status, why exactly the tribe’s efforts to gain a marae at Te Henga were frustrated, and how exactly the second confiscation at Ihumātao occurred.

To sum up, the first two examples – the Titford farm case and the Te Henga Marae site purchase show how tricky, drawn out and rare it can be for Māori to get the Crown or Councils and other interests to either stump up for privately-owned land. The Titford case shows an unwillngness by the CRown to fess up to the machinations that underpinned the derailing of Waitangi Treaty claims including the Crown directly purchasing privately-owned lands – specially in light of Allan Titford’s convictions in 2013, including arson for incinerating his own farmhouse to the ground. It also reveals the murky role played by former Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB) detective, Ross Meurant, who failed as a Member of Parliament in the Bolger-National Government to investigate Titford’s claim that his house had been arsoned. Suspiciously, Meurant rang The New Zealand Herald instead. Intriguingly, the Police failed to conclude the obvious. The former 2IC of the Riot Squad, in effetc, made a ‘heralding play’ that advanced the game to undermine Māori ancestral claims to privately-owned lands by not only signalling to Police to not investigate the suspicious fire too hard. Since Meurant was also a Member of Parliament in the Bolger-National Government, his codified communication via a national newspaper that was started on November 13th 1863 to be “a mouthpiece for those colonists who were demanding a more vigorous prosecution of the [Waikato War]“, he was also gazetting there would be not cross party Parliamentary Select Committee investigation. By heralding this codified communication, the former CIB detective – who stayed quiet for 40 years about the planted .22 cartridge shell in the Crewe’s farmhouse garden – was signalling that Parliament under a Bolger-National Government would not be using its subpoeana powers to call witnesses in the Te Roroa-Titford land dispute.

The Te Henga Marae case shows that the Waitakere City Council and Auckland Council deliberately embroiled in Te Kawerau ā Maki in stonewalling tactics to frustrate gaining title to land to build a marae and papakāianga housing. While the Waitakere Council had to contend with a backlash from Pākehā residents, its unwillingness to front-foot such resistance is commensurate with its own machinations to delay the project. This process, which has been occurring for 21 years, appears to be ongoing, as it seems the land at 240A Bethells Road is still owned by the Auckland Council.

On the surface, the second two examples show how tricky it is for Councils to transfer land to Māori, either when a Council already owns the land, or when a Council buys the land for Pākehā, only to be challenged by Māori ancestral claims. Te Atatū Marae case was drawn out by Pākehā whom either opposed a small proportion of the Council-owned park on the Te Atatū Peninsula being gifted to a Māori entity, and by seven Pākehā families who wanted the land back, since it had been acquired for a port facility in 1958 under the Public Works Act, but this project never eventuated. However, when this Te Atatū Marae project is compared with the concurrent efforts of Te Kawerau ā Maki to gain a marae and village housing property at Te Henga near Bethells Beach, the complication of a concerted Pākehā backlash is less forgivable. The Waitakere Council’s unwillingness to front-foot this Pākehā backlash over Te Atatū Marae project is commensurate with its own machinations to delay the Te Henga Marae project. The West Auckland Council’s unwillingness to front-foot resistance among some Bethells Beach residents, is commensurate with the Waitakere City Councillors’ silence over Te Warena Taua and Fletcher Building and the Establishment News Media misleading New Zealanders that Te Kawerau ā Maki are the local iwi of Ihumātao. The Waitakere City Councillors’ silence is commensurate with their Auckland City Councillors’ silence, including incumbent Mayor Phil Goff.

All four fraught cases show how difficult it is to get racist Pākehā on board to accept that resourcing tangata whenua – or ‘the people of the land’ – with the very thing that would not only complete the phrase. Resourcing Māori would actually build resilience, sustainability, and dynamism into New Zealand communities.

Furthermore, the meta-data in the Te Henga marae site case showed that at least three mechanisms exist, in addition to local body or central government legislation, for the transferrance of land to Māori: either a Gazette Notice, an Order in Council, or a Proclamation.

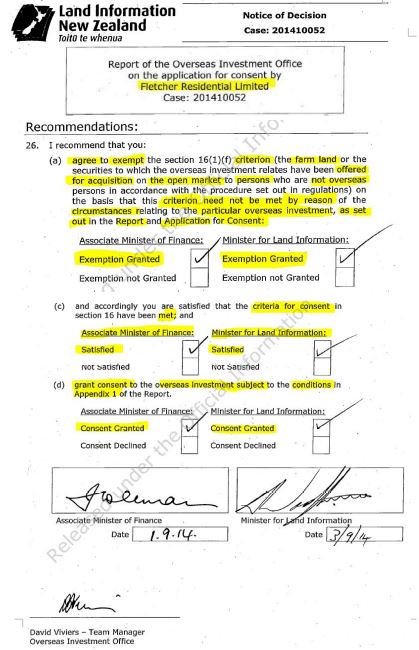

It is not only ironic that the land at Ihumātao was originally lost through Freemason Governor Bro. George Grey’s proclamation of July 9th 1863, an Order in Council of May 16th 1865, several Gazette Notices of 1866 to auction the lands, and finally Bro. Grey’s Crown Grant of 28th December 1867 to Scottish Methodist farmer Gavin Struthers Wallace. It is ironic also because, in effect, a second confiscation occurred through a joint waiver by two Crown Ministers in September 2014 to over-ride breaches to the Overseas Investment Act of 2005. The Wallace-Blackwell Family company, Gavin H Wallace Limited, owner of ‘the Wallace Block’ – as the highly contested land at Ihumātao is locally known – failed to advertise the farm land on the open market prior to sale to the transnational construction company, Fletcher Building. In other words, the polite racism behaviours, collusion and stonewalling revealed in these case studies of fraught land buy-backs, also extends to the Neo-Colonial Crown over the Ihumātao land dispute.

The key finding of this investigation is that: the permanent embargo blocking the Waitangi Tribunal from recommending private land buybacks was, in no small part, the result of farmer Allan Titford burning his own house down in 1992. The Crown, Councils and Courts continue to practice contrived ignorance about the racism they are complicit in maintaining, as matter of self-preservation. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s politely racist Pākehā Ruling Class maliciously play Māori in drawn-out processes in the few existing cases of land transfers. Such stonewalling extends to maintaining a contrived ignorance about where exactly Te Kawerau ā Maki holds tangata whenua status, why exactly the tribe’s efforts to gain a marae at Te Henga were frustrated for 21 years, and how exactly the second confiscation at Ihumātao occurred between 2014 and 2018.

=======

Editor’s Note: Please let me know if I have made any errors.

e: steveedwards555@gmail.com