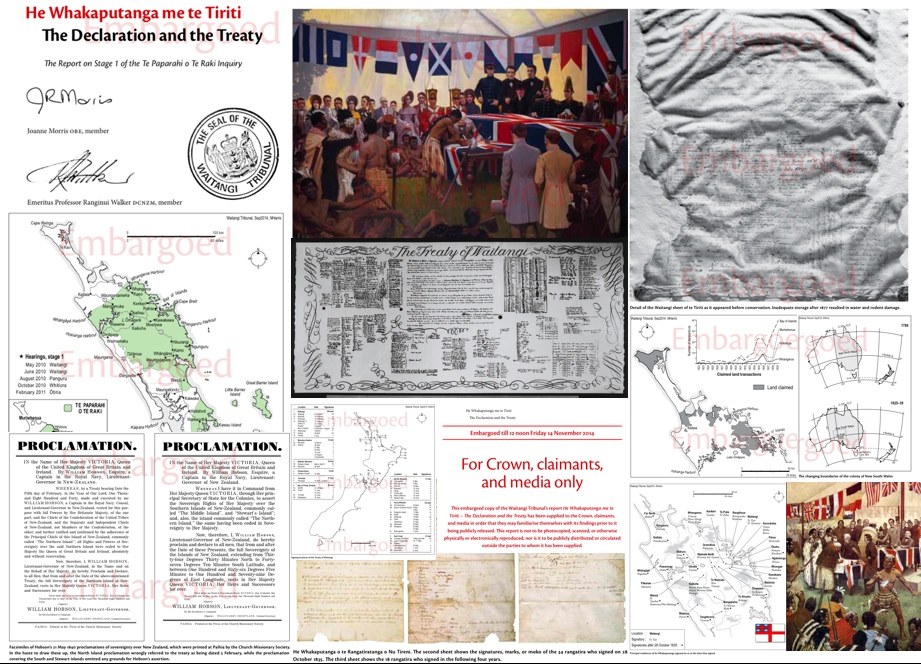

How the British Take-over of New Zealand Happened

Overview: In 1839, by her royal seal, Queen Victoria authorized the perfect power crime to swindle full sovereignty from an entire aboriginal and indigenous peoples by pen-quill, parchment paper and treaty theater for the expansionist British Masonic Empire.

Moreover, two parallel tracks — a ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ and a ‘Colonial Law Track’ — were laid during the British takeover of N.Z., as this heretical exposé proves. The Treaty would save face for the Monarch, at a time when annexations drew rebuke.

The Treaty Theatre Track began in June 1831 when future British Resident James Busby essentially outlined his dream job description to make treaties with Māori.

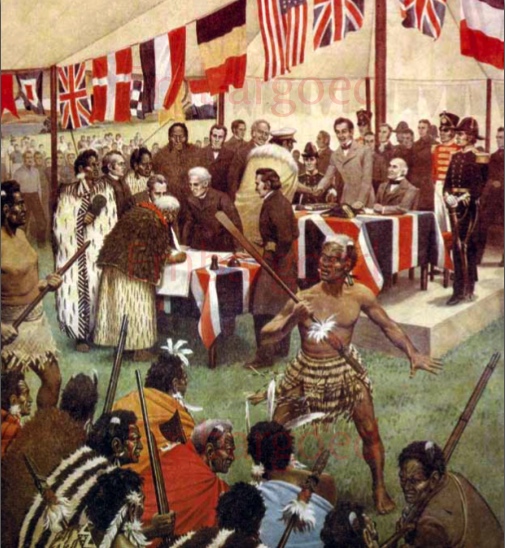

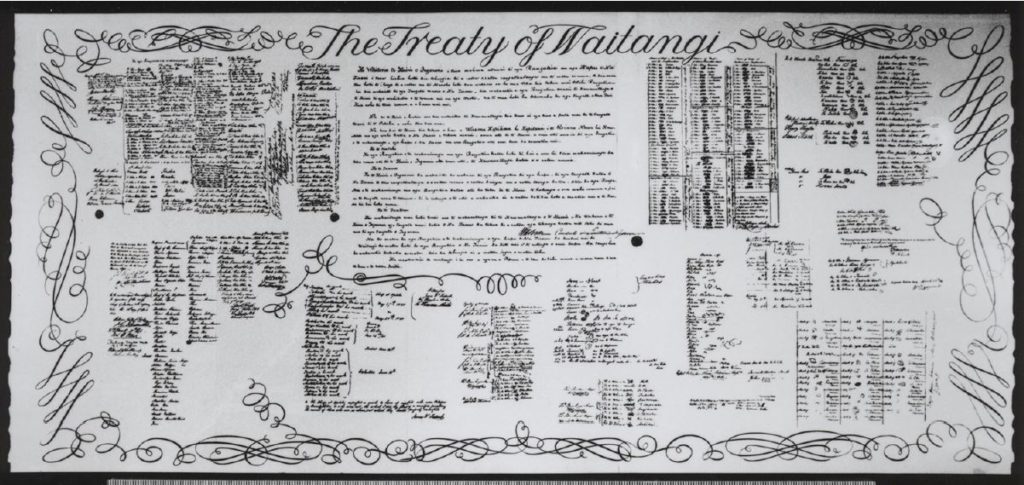

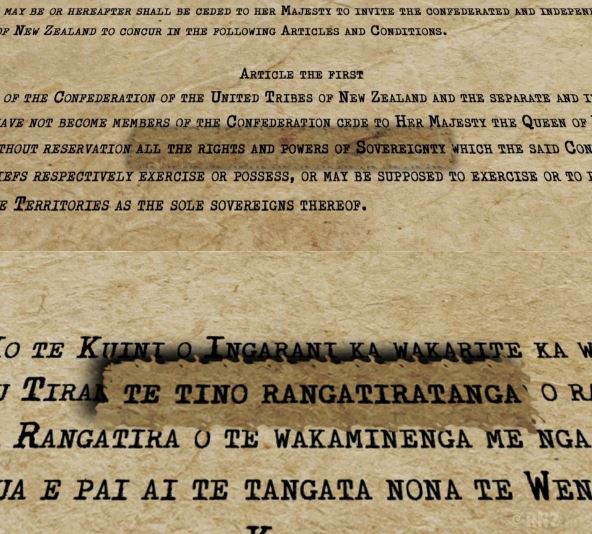

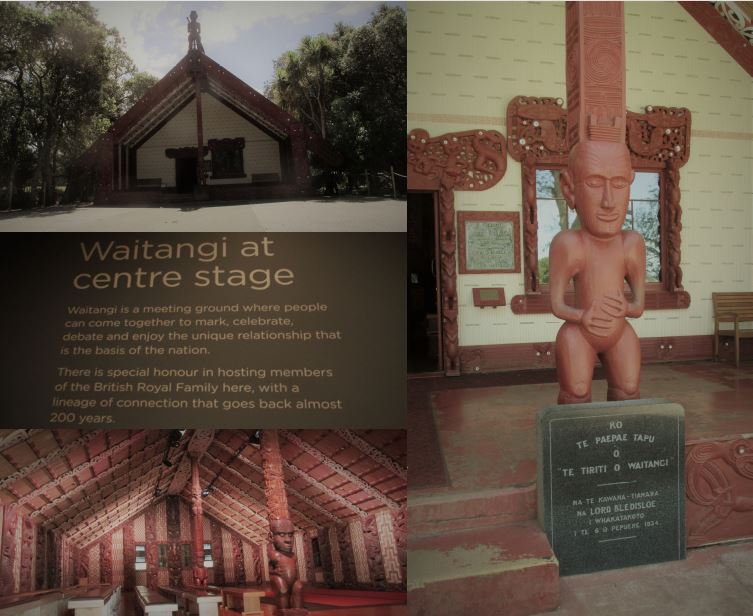

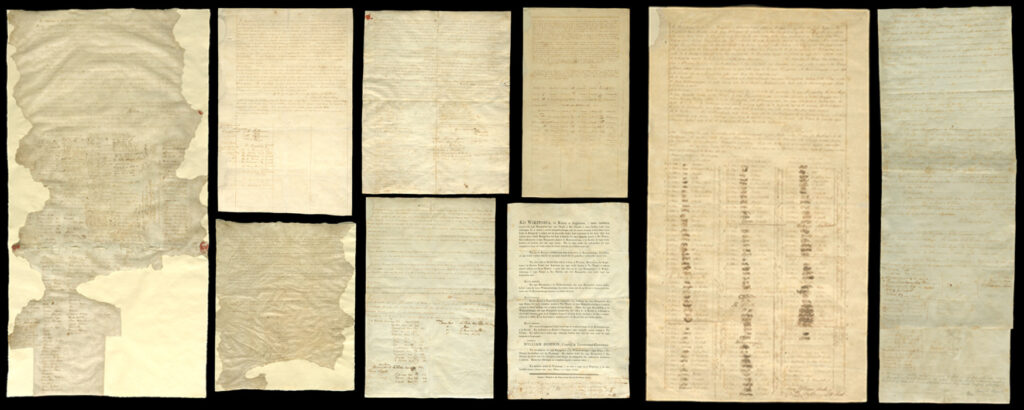

In deed and in design, the 1840 Waitangi Treaty parchments spun with unseemly speed on a fulcrum of deceptive language translation differences, poorly recorded oral promises and a simulation of a sacred covenant. In the language of the imperial power, sovereignty was construed to be willingly transferred.

All the while, full sovereignty was retained in the native language version. The stage production of the ‘Waitangi Treaty Theatre Company’ supplied the documentation to create the nation’s founding myth: cession by treaty.

This epic swindle of bi-lingual innovation was necessitated by the fact that the aboriginal and indigenous people of New Zealand would never consent for their chiefs and chieftainesses to give away their sovereign authority. The Treaty Cliqué later construed that the Treaty Chiefs had consciously and freely signed away sovereignty, without mentioning Māori relied heavily on lying, unprincipled missionaries.

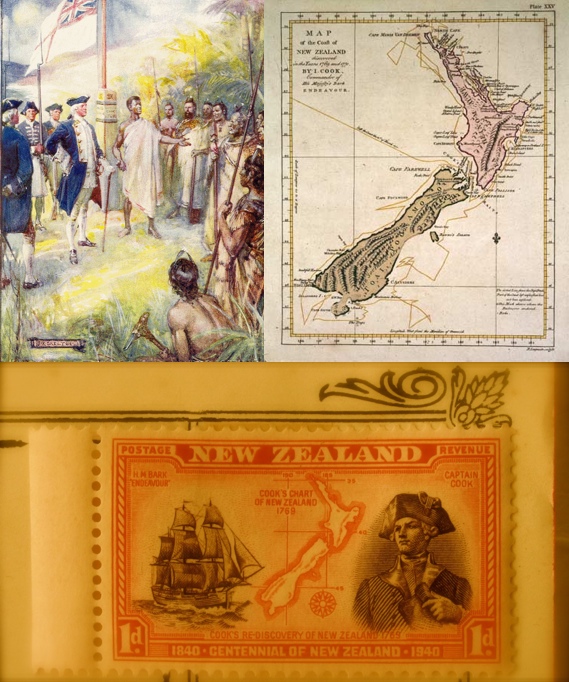

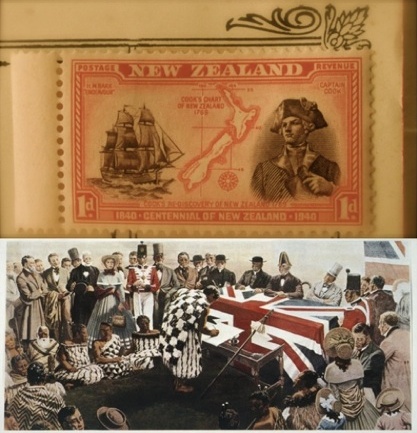

Whereas, the Colonial Law Track was the primary route through which the completion of the annexed title claimed by Freemason Bro. Captain James Cook actually occurred. Indeed, the ‘Endeavour Voyage’ in 1769-1770 was New Zealand’s first travelling theatrical production, while the Waitangi Treaty Theatre was the second big budget show staged to distract, divide and defeat.

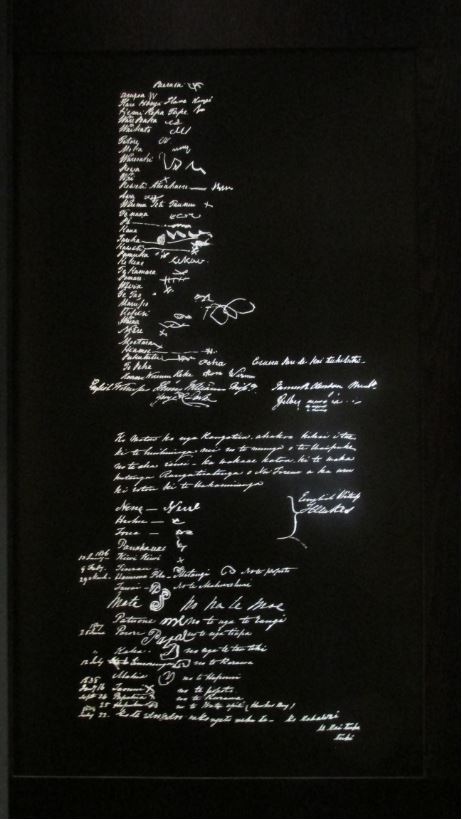

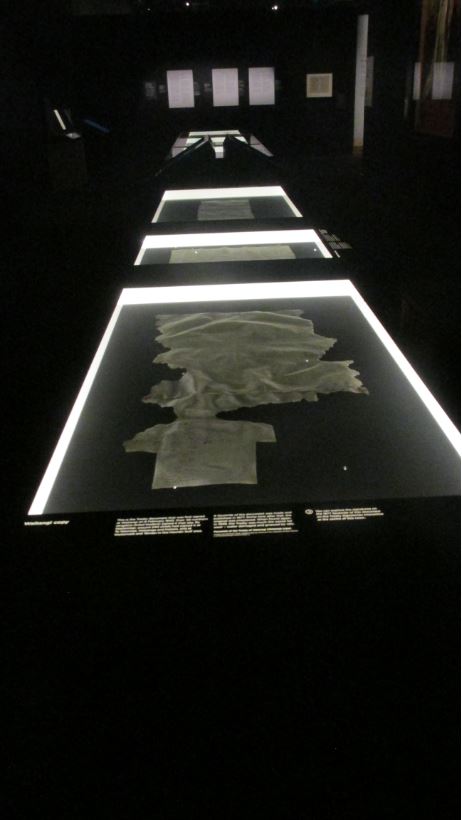

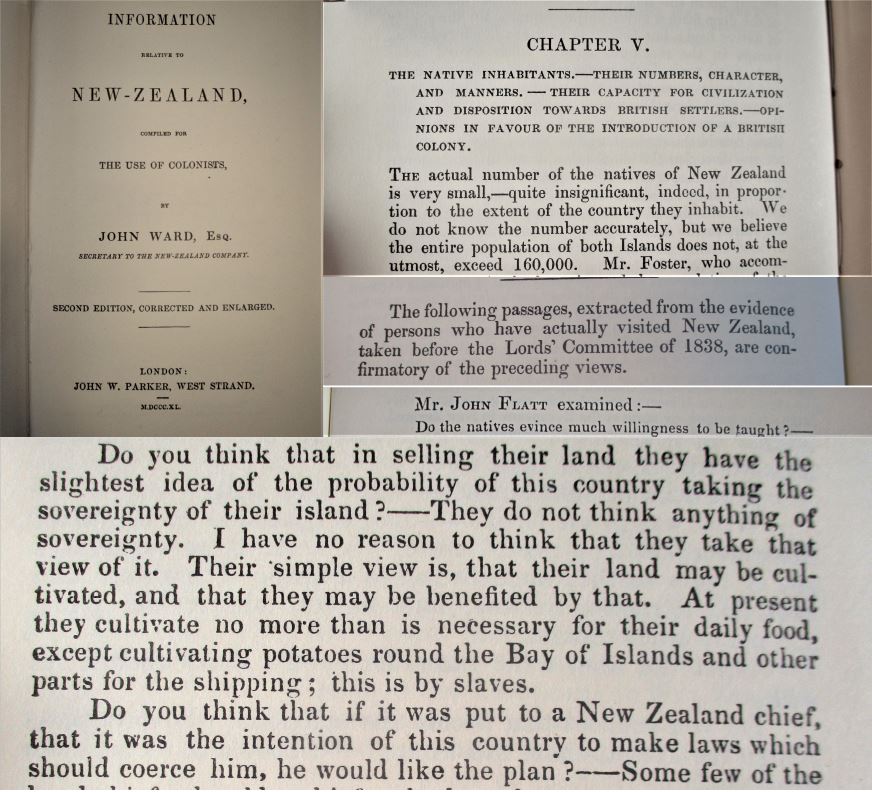

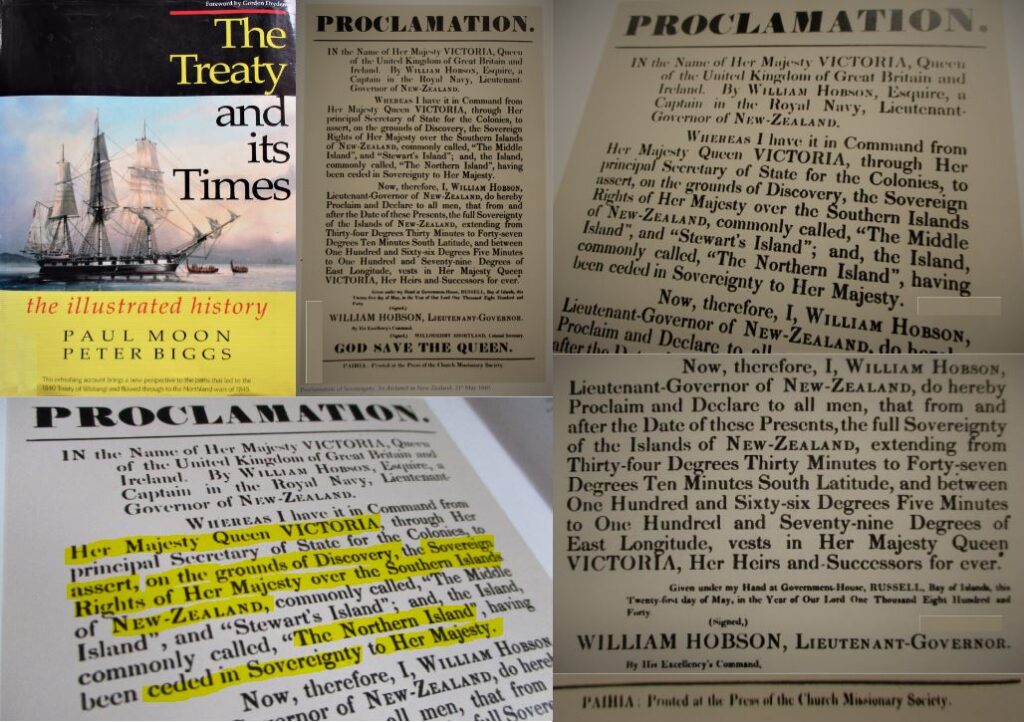

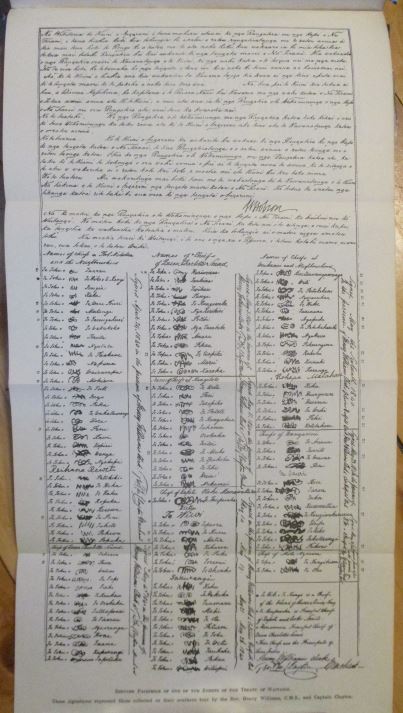

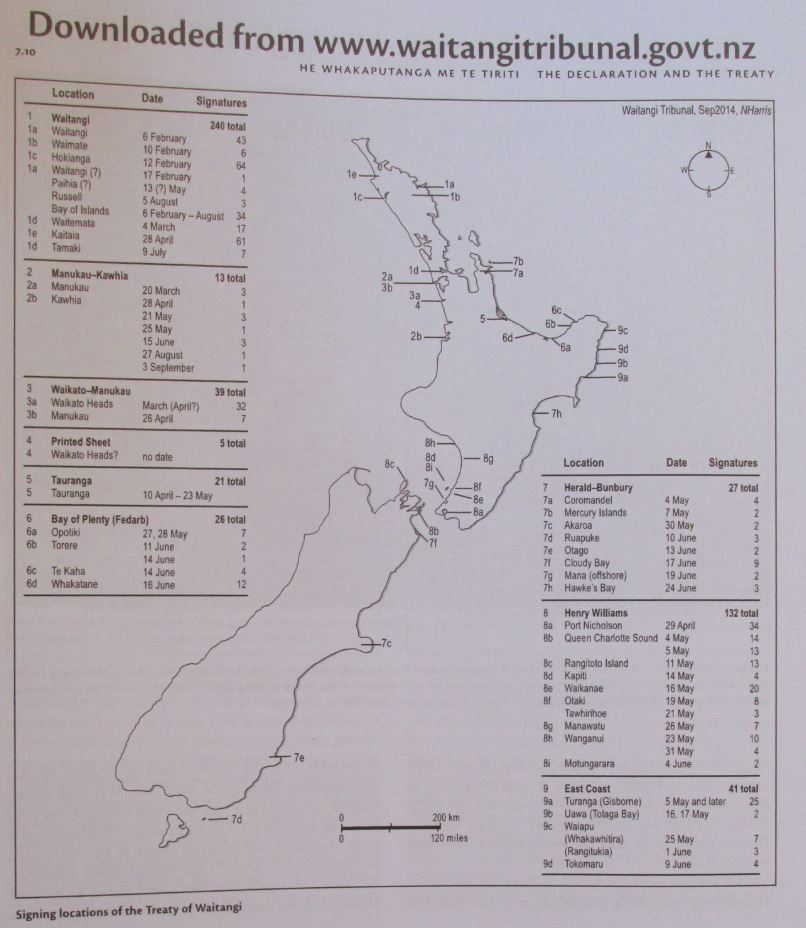

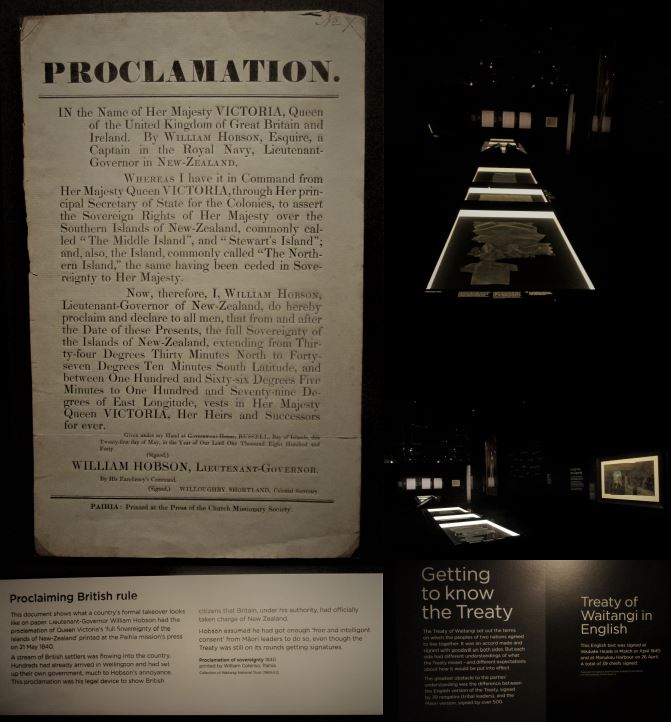

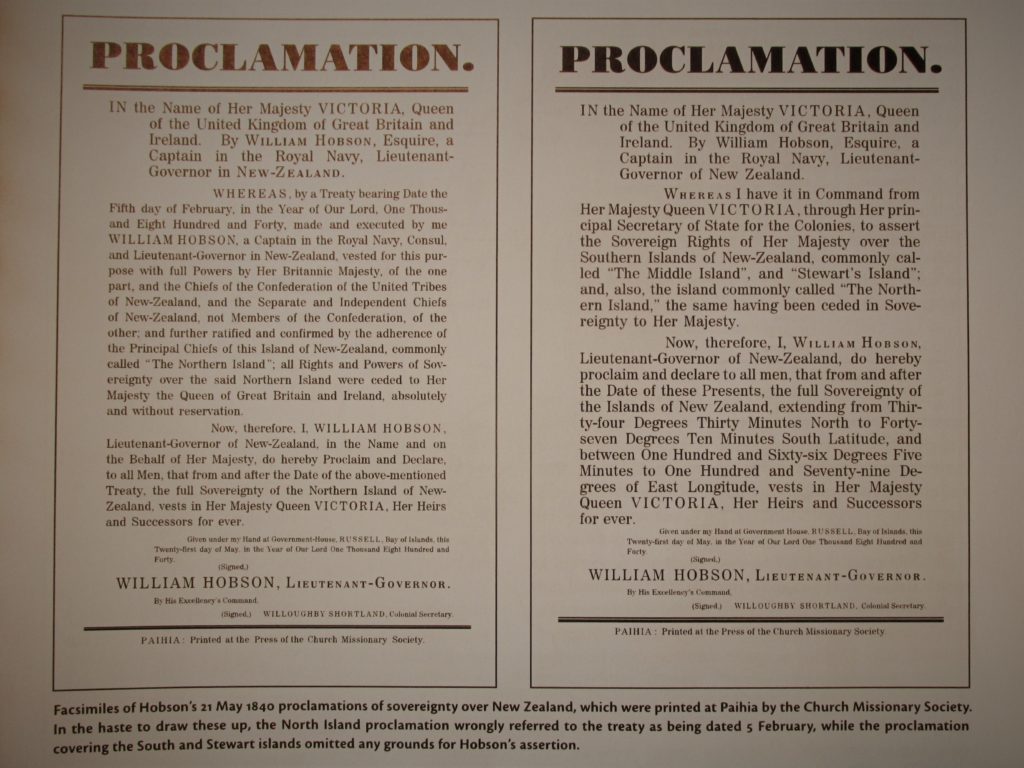

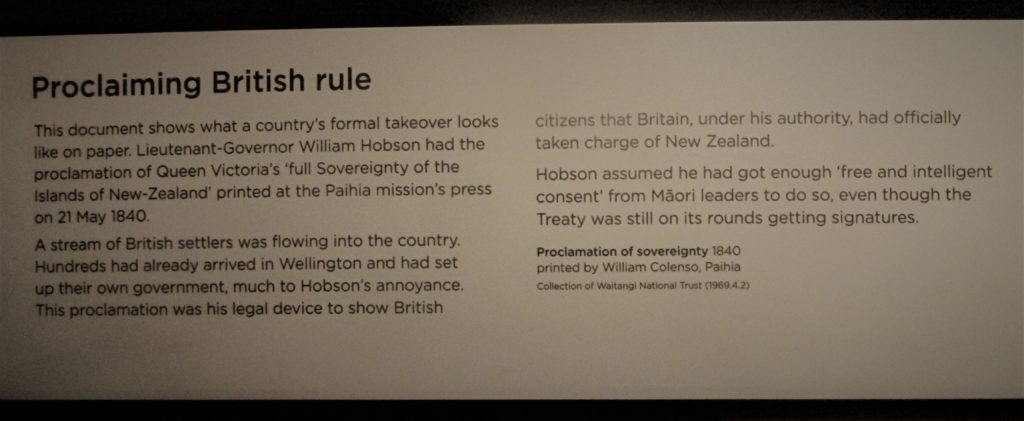

The main trunk line of new ‘Colonial Law Track’ was laid in 1839, 1840, and 1841, with the roll-out of legal instruments prior, during and after the hasty hawking of the nine Treaty parchments around New Zealand coast-lines; a feat that swindled signatures and marks from 527 Māori rangatira (or chiefs) and 13 wahine (women). The legal instruments included proclamations, new commissions, swearing-in officials, letters patent, legislation, gazetted notices and a royal charter that solidified the establishment of New Zealand as a separate colony of the British Masonic Empire.

Therefore, this exposé “Deep History of Waitangi: The Queen Victoria Connection”, looks at the 1840 Waitangi Treaty clustered events as part of a broader innovation of trickery — treaties with aboriginal and indigenous peoples. This “Deep History of Waitangi” also reveals the novel twist of swindling full paper sovereignty from an entire people, with the brazen expectation that a chiefly majority would not be gained by peddling the parchment copies around the coastline of the South Pacific Archipelago.

Meanwhile, the final stage of crucial chess moves along the Colonial Law Track were started and finished by the hand of Queen Victoria, of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Her Majesty’s seal of approval to circumvent the British Parliament meant that under English Law, her claim of title to the newly erected colony was unchallengeable, despite the inherent fraud.

Four ‘Clanker Moments’ at Waitangi demonstrate that a Treaty Cliqué consciously avoided fully disclosing to Māori there was trickery afoot, while the ‘theatre production’ proceeded with unseemly haste. The contextual facts of these clanker moments remained unspoken at Waitangi and, therefore, they remained ‘at-large’ for historians to piece together later. Until now, however, the four clanker moments have not been identified as such and their deep significance reveals the rivalry between four empires that intersected at Waitangi.

Moreover, Māori at Waitangi were unaware that a secret piece of international law, known today as the Doctrine of Discovery, was applied during the 1840 Waitangi Treaty Theatre. This Discovery Doctrine was ‘transported’ on both tracks, and intersected briefly at Waitangi, where time had been weaponized to gain control over a new territorial-jurisdictional space for the British Masonic Empire.

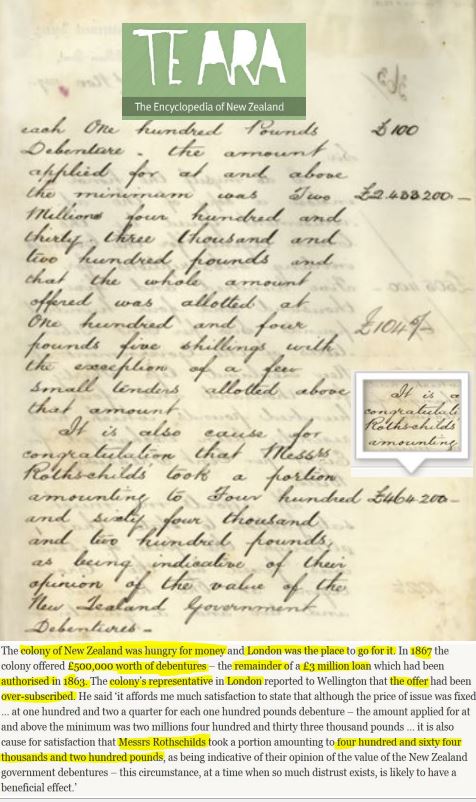

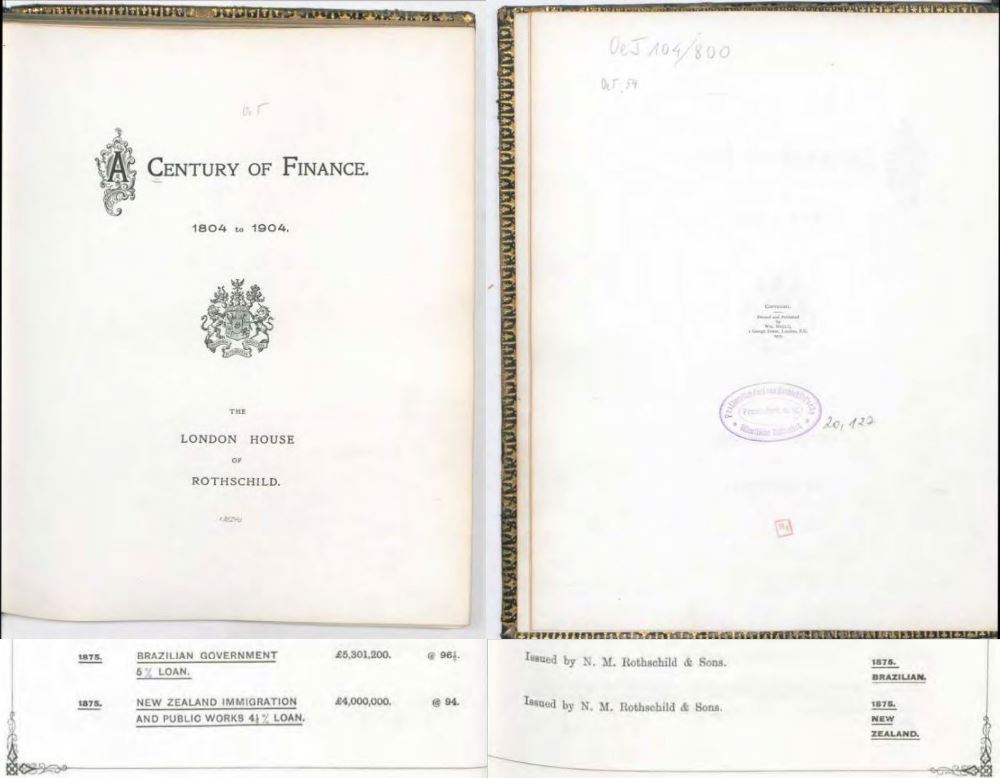

Steve ‘Snoopman’ Edwards locates his study of this epic heist in empire literature, the revolutionary dynamic model and power crime theory. Central to this ruse was establishing a colonial apparatus to represent the British Crown in matters such as land purchases on the cheap. Substantive development finance in New Zealand would be withheld until it was clear that the British had been victorious in the conquest stage, in accordance with the Discovery Doctrine.

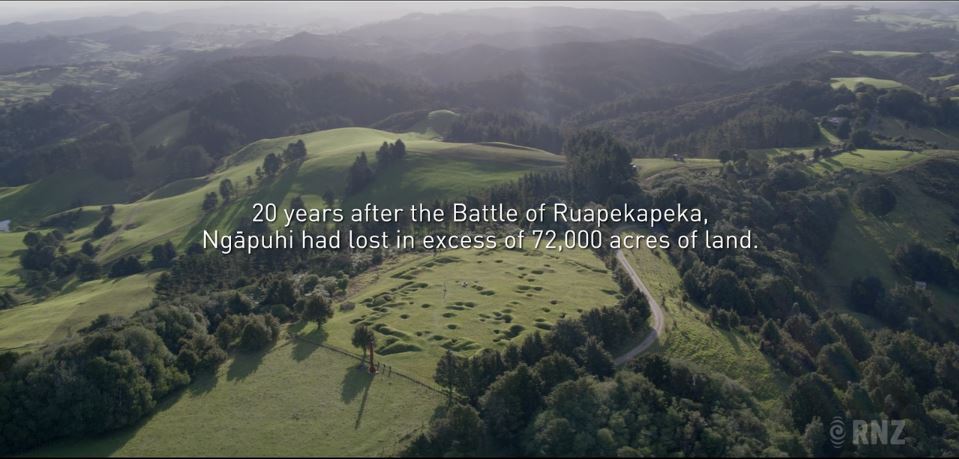

Thus, the machinations of 1839-40 would inevitably led to war. The gambit envisaged British Masonic Imperialism would win substantive sovereignty over the soil by swindle, struggle and stealth, since the leading immigrants would be a more loyal breed to the British Monarch. The eventual New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872 consolidated the swindle.

The key finding of the “Deep History of Waitangi: The Queen Victoria Connection”, is that the British takeover of Aotearoa occurred by the two parallel tracks — a ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ and a ‘Colonial Law Track’ — and were innovative cunning tricks in statecraft to gain full paper sovereignty over an entire aboriginal and indigenous peoples that could never be repeated, lest the perfect crime became obvious. The decision to opt for a Treaty was pursued to save face for the British Monarch, by achieving the appearance of sovereignty cession to Queen Victoria.

Getting legislation passed to claim New Zealand in the British Parliament would have attracted the attention of the French, American and Vatican Governments, thereby risking the enterprise to gain a far-flung colony on the cheap, without firing a shot. Amid the complications of running the British Masonic Empire, the imperial ‘need’ to acquire sovereignty over New Zealand occurred at a time when the high priest of British Freemasonry, Lord Palmerston, was planning the first of two wars with the civilization that invented the very medium upon which the fraudulent bi-lingual Treaty copies were written: China.

The significance of the Waitangi Treaty as a theatrical production, or théâtre usurp d’état is the object itself, as a literary device, was designed to distract from the Colonial Law Track. This finding means the 1840 compact was, in fact, a red herring mechanism to sponsor logically fallacious arguments to divide and defeat. The intention was to lead its audience to a false conclusion. The Waitangi Treaty Theater was, in effect, a simulation produced to create a copy of reality to eventually forge subject race pacification.

The Treaty Cliqué responsible for the British takeover of paper sovereignty in the period leading up to, during, and in the immediate aftermath of ‘The Great British Waitangi Treaty Swindle’ are identified as they appear in the narrative. The supposition proven here is that while the Treaty Cliqué raced toward the endgame to capture new political space via a sovereignty payload, they acted like a travelling theater company to weaponize the one physical dimension they could control though emotional hijacking, Orientalist swagger and novelty: time.

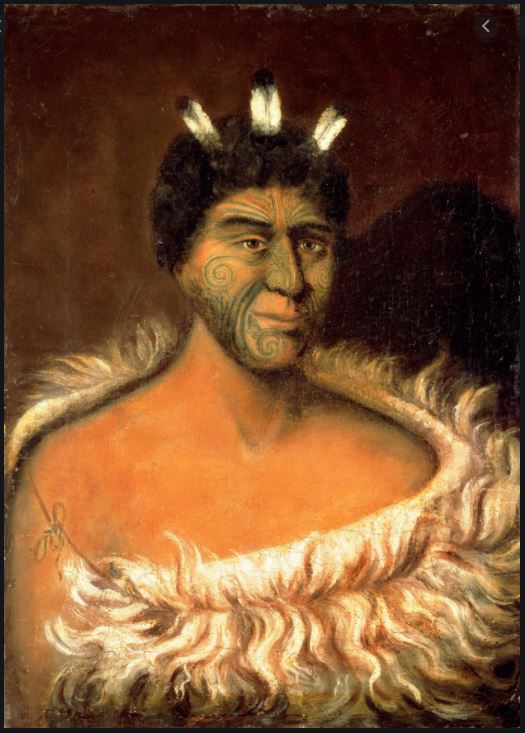

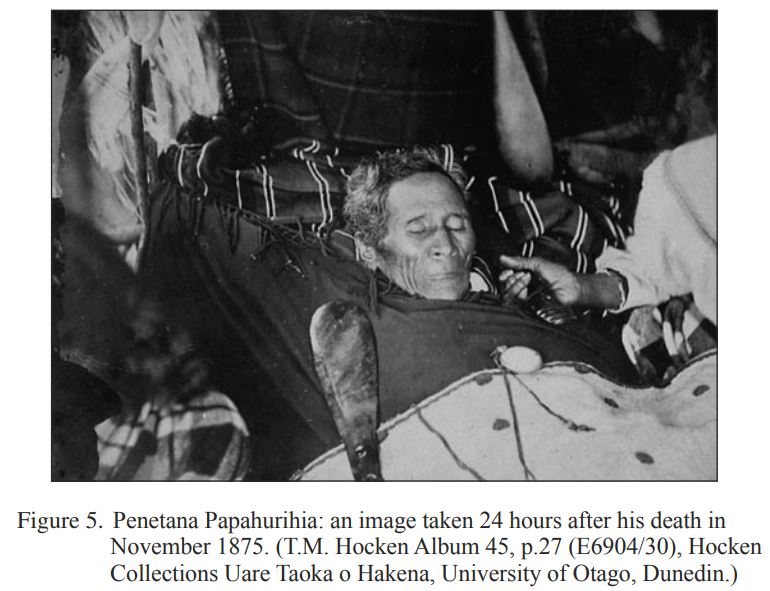

“Kua mau tātou ki te ripo. Kāti ka taka ki tua o te rua rau tau ka tū mai te pono ki te whakatika i nga mea katoa”.

“We have been caught in a whirlpool. Alas, it will last for beyond 200 hundred years when the truth will stand to put everything right”.

— Prophet Penetana Papahurihia after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, 1840 [1]

By Steve ‘Snoopman’ Edwards

British Takeover by Two Parallel Tracks

Māori chiefs, hapū and iwi were manipulated by British agents, missionaries and other settlers, to trek along a track, through incremental steps, to the 1840 Waitangi Treaty, which was a theatre production that traversed the coasts of New Zealand — with unseemly speed.

In the pre-colonial era, many among the aboriginal and indigenous peoples of the South Pacific Archipelago, New Zealand, were led to believe that by their own agency in such steps, that they would retain their mana and tino rangatiratanga, or sovereignty authority, as self-determining people.

A revolutionary long-game was played, where time was ‘quickened’ around such events so that the British side achieved their objectives at every incremental step, amid set-backs. By weaponizing time dawn to dusk, and dusk to dawn, this periodically sped-up fourth physical dimension became the key mechanism to gain a new territory for the British Masonic Empire, until the job was ‘done and dusted’.

It turns out, two parallel tracks — a ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ and a ‘Colonial Law Track’ — were laid during the British takeover of New Zealand.

The main trunk line of new ‘Colonial Law Track’ was laid in 1839, 1840, and 1841, with the roll-out of legal instruments prior, during and after the hasty hawking of the nine Treaty parchments around New Zealand coast-lines; a feat that swindled signatures and marks from 527 Māori rangatira (or chiefs) and 13 wahine (women). The legal instruments included proclamations, new commissions, swearing-in officials, letters patent, legislation, gazetted notices and a royal charter that solidified the establishment of New Zealand as a separate colony of the British Masonic Empire.

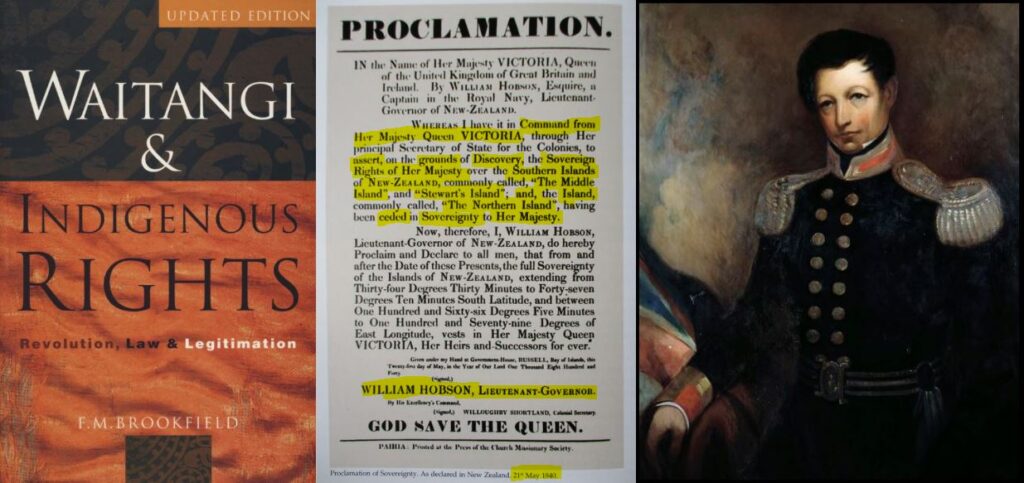

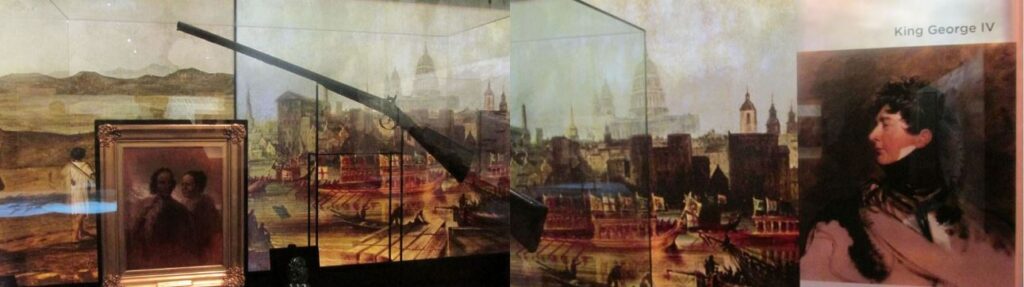

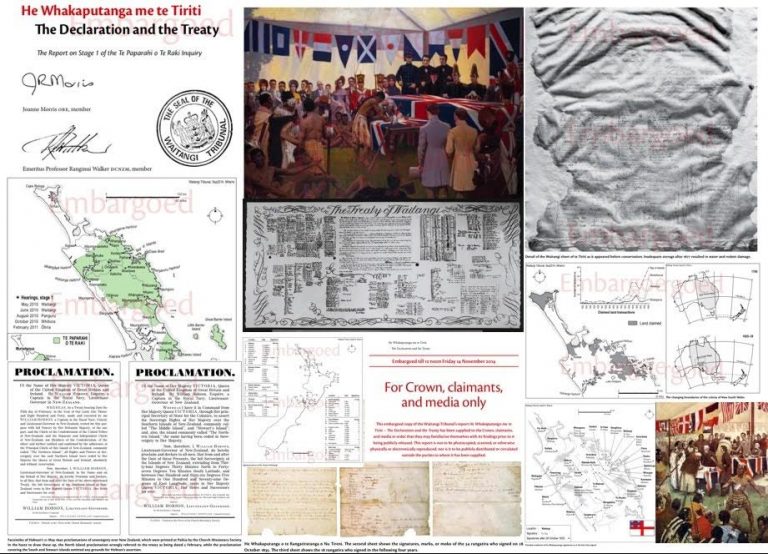

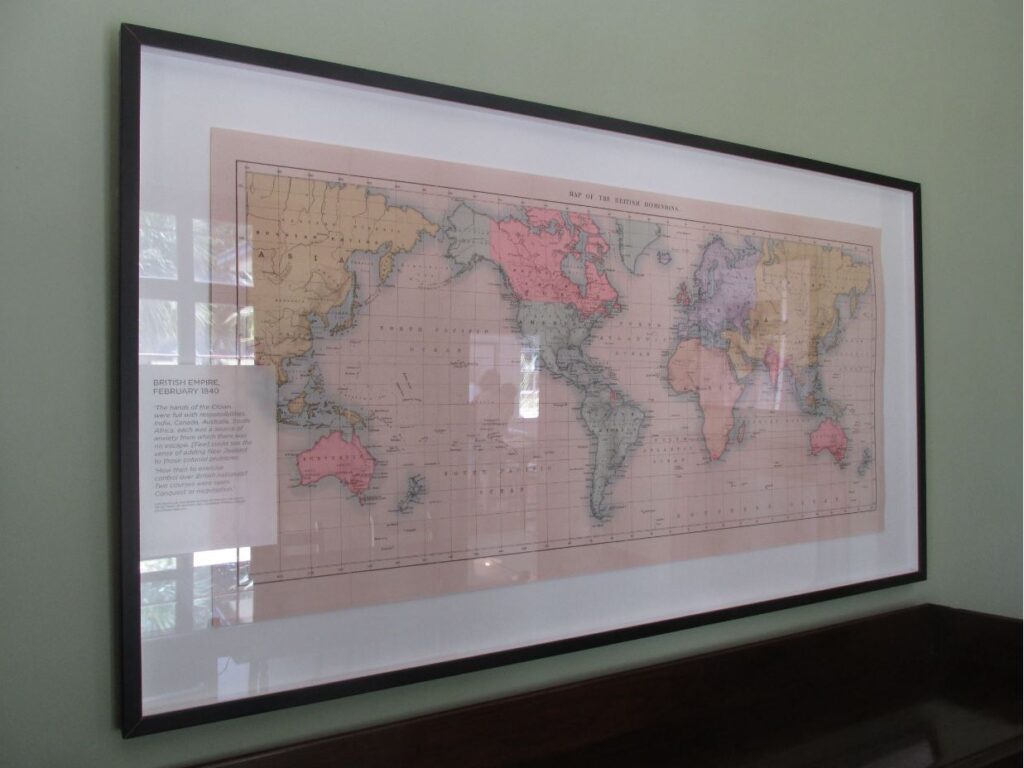

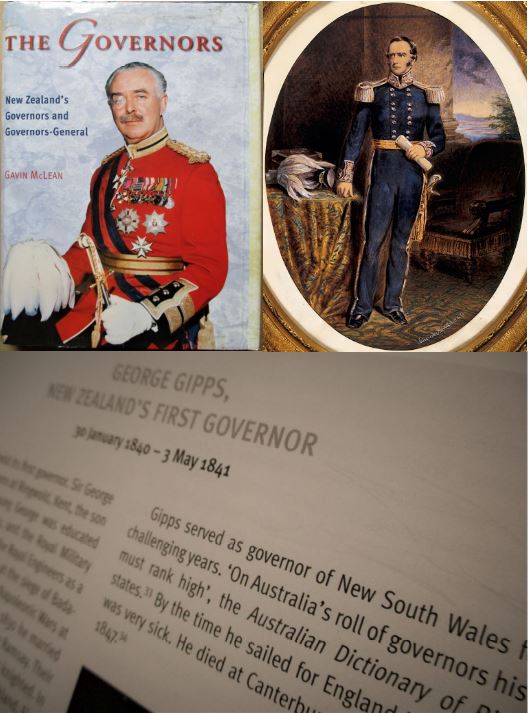

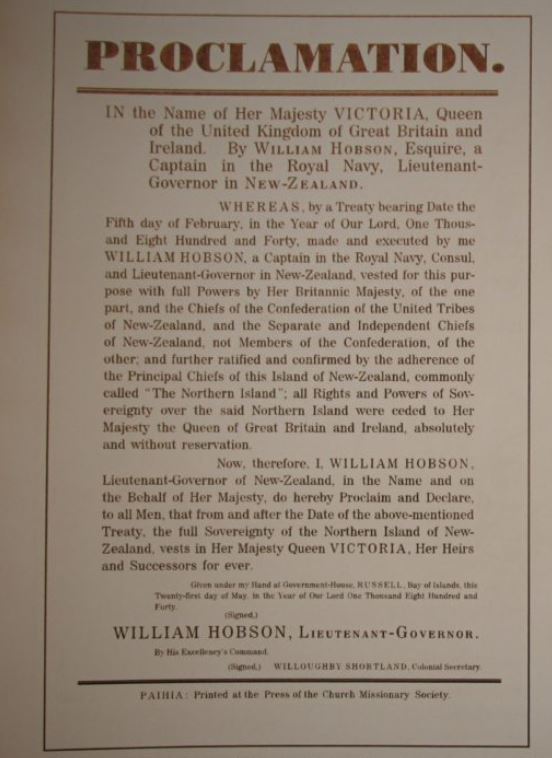

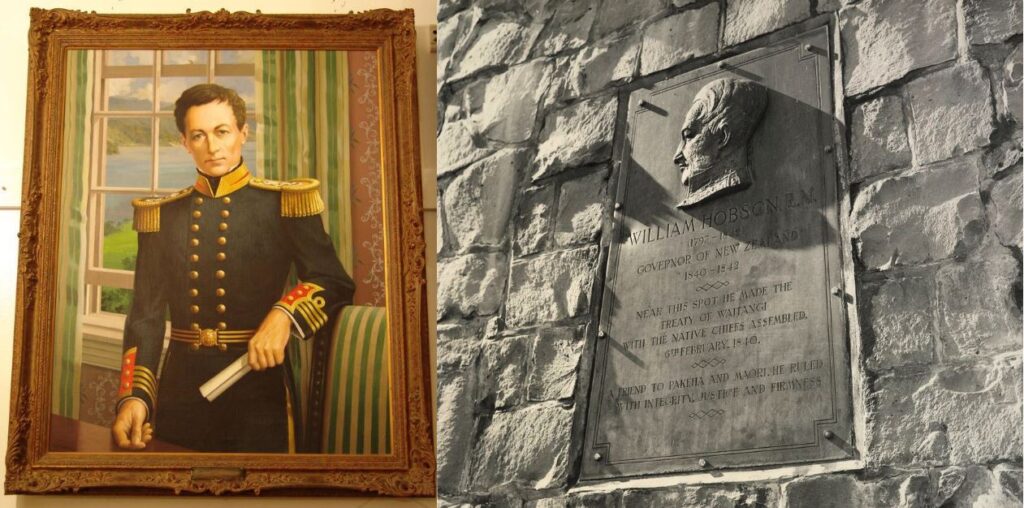

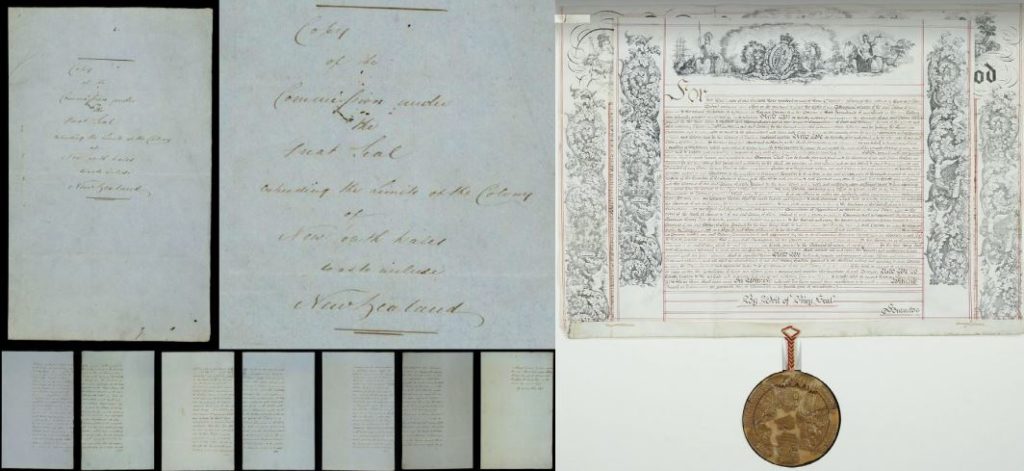

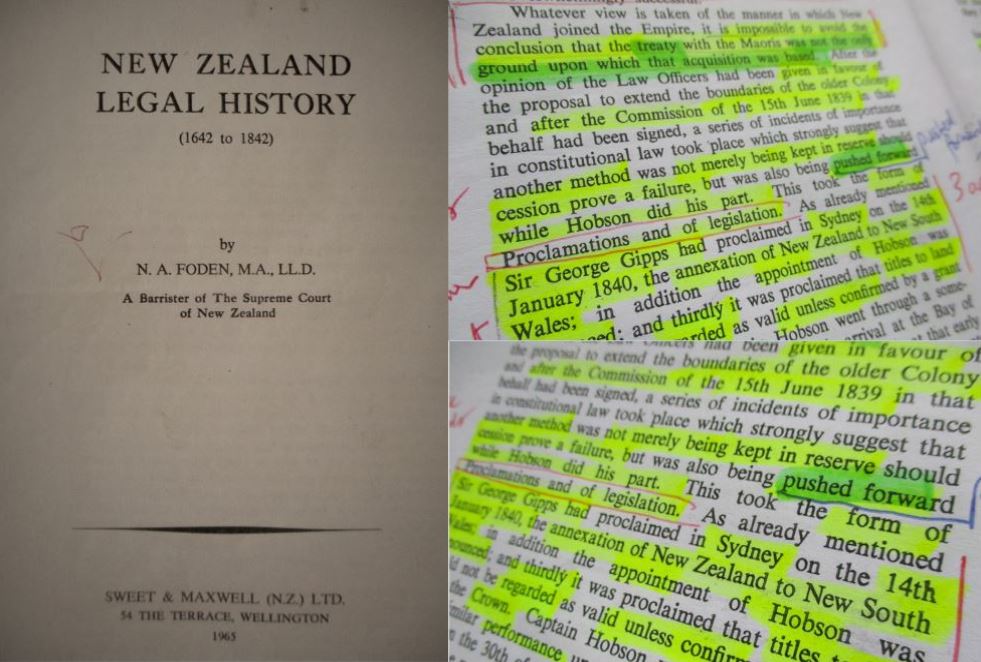

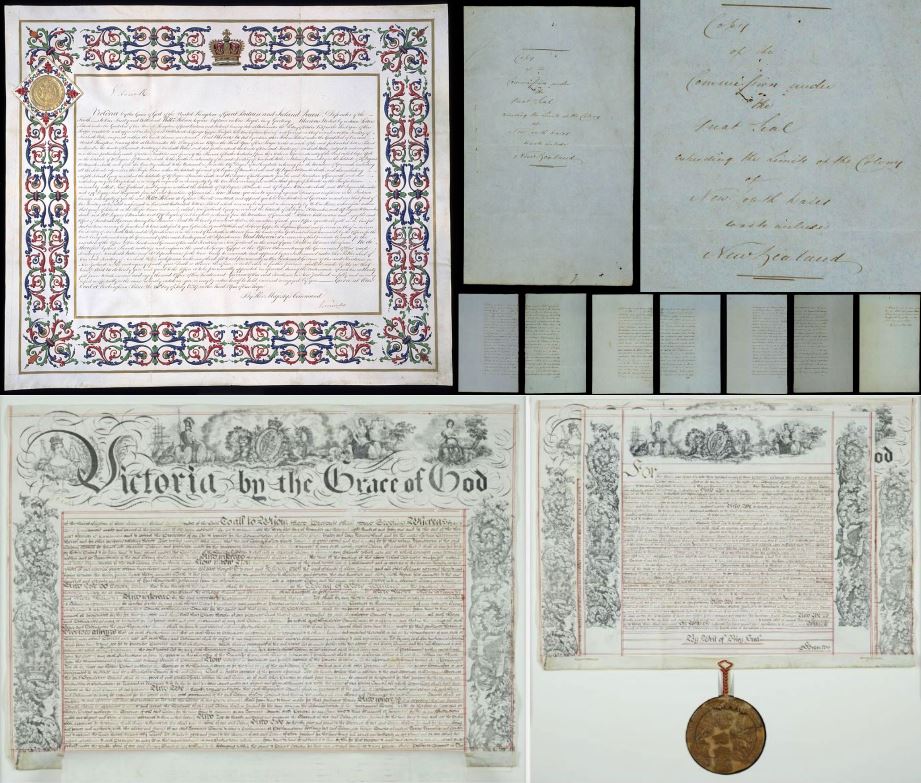

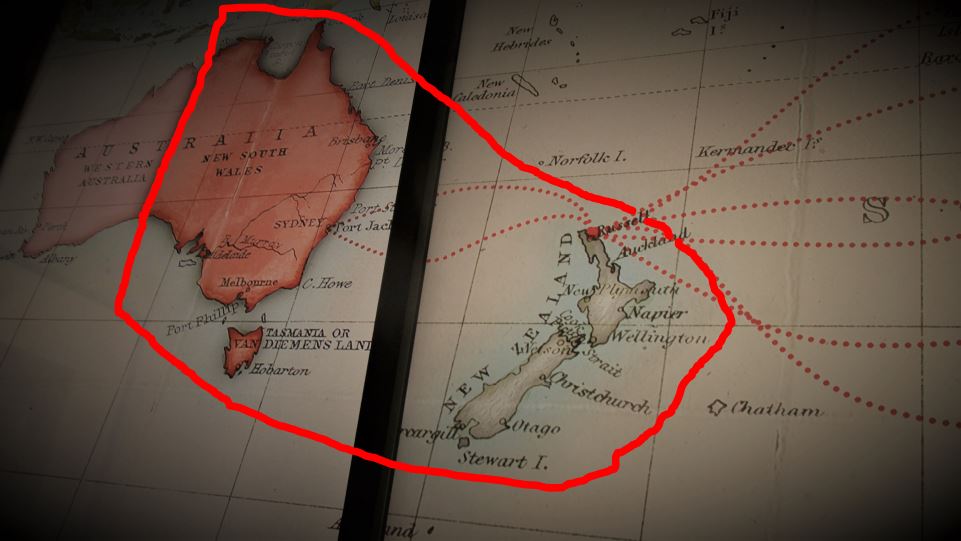

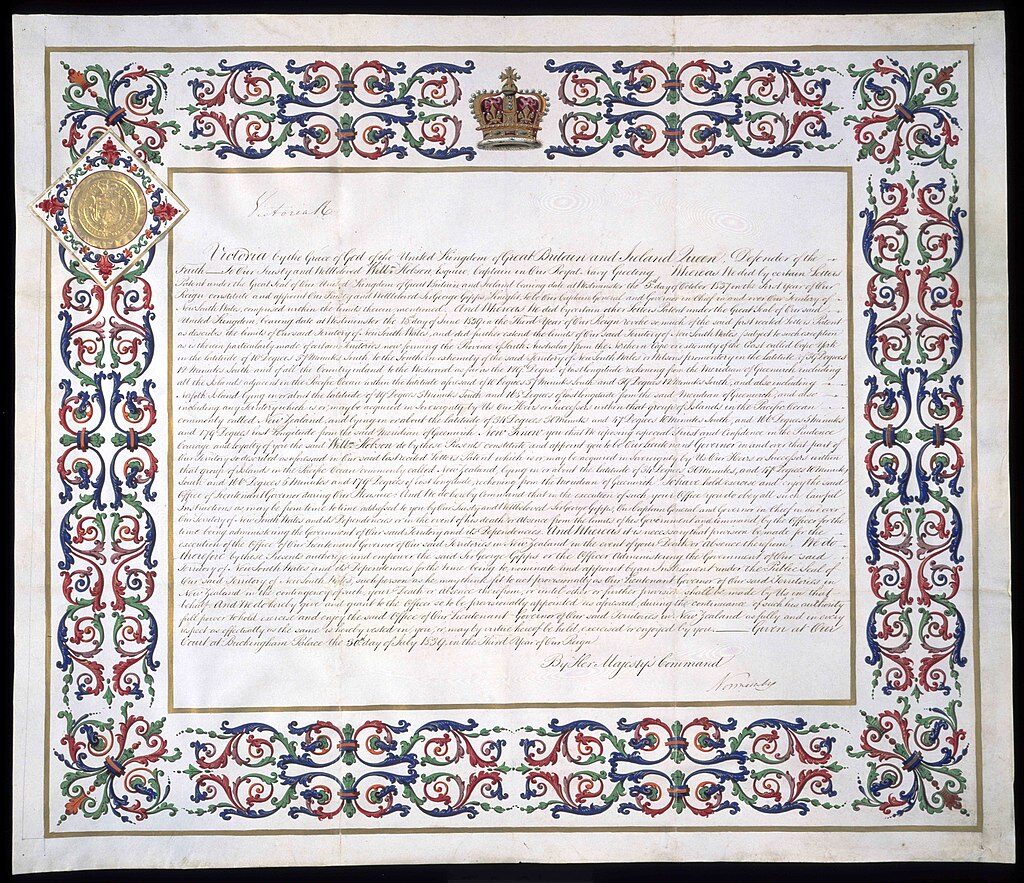

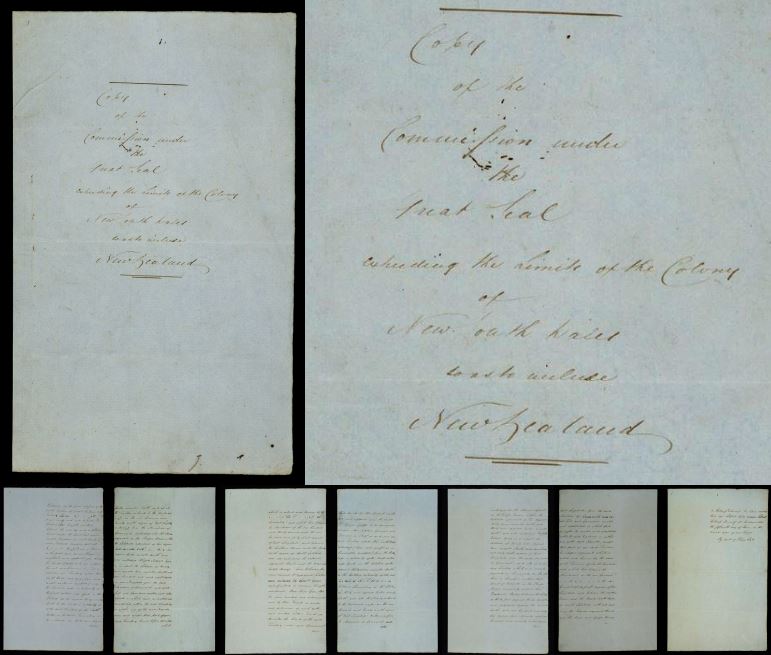

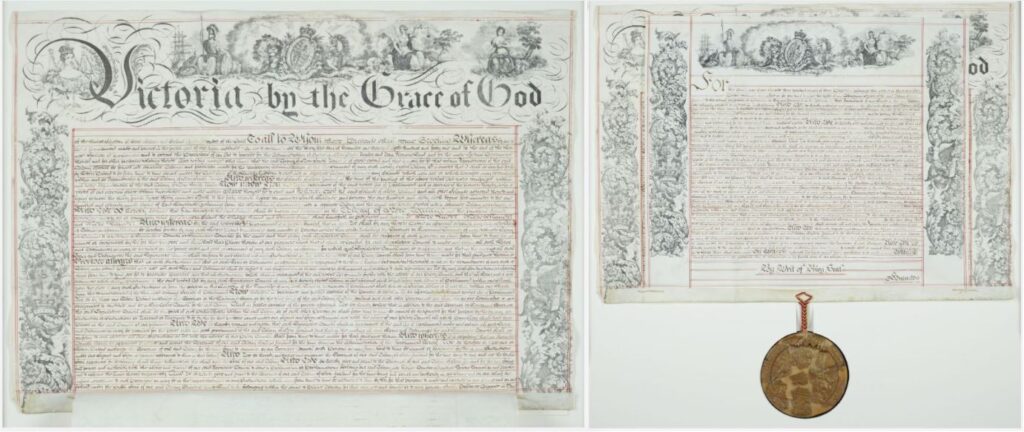

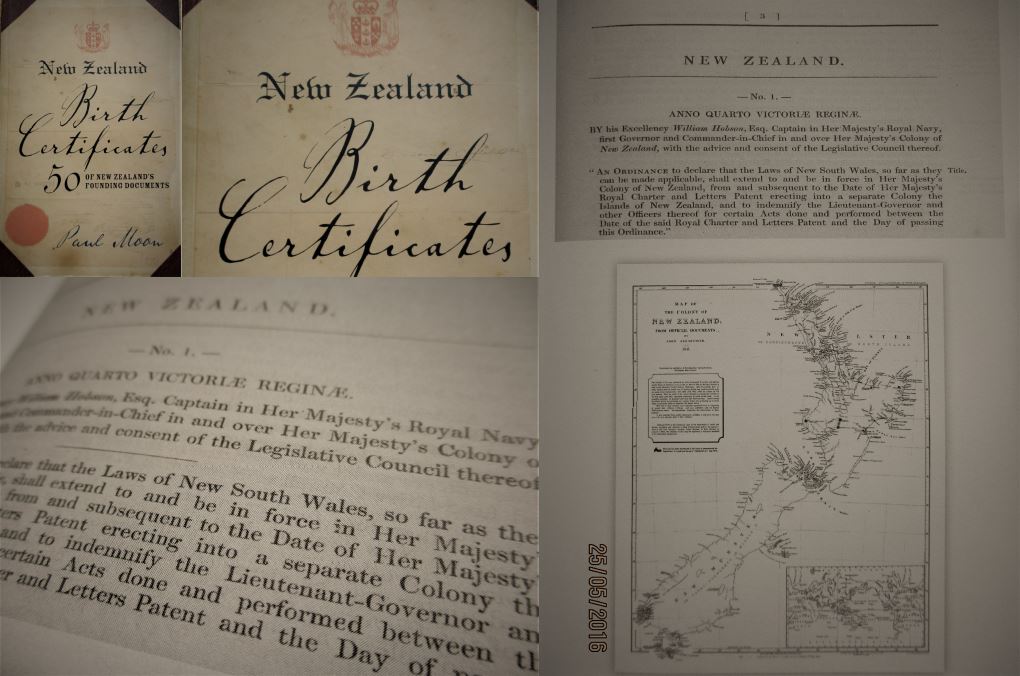

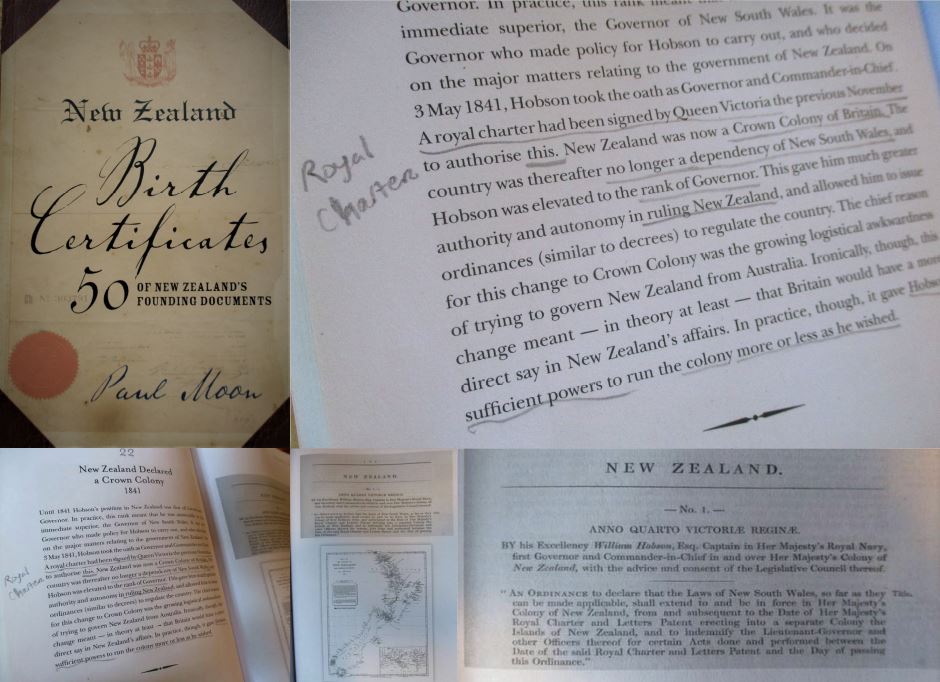

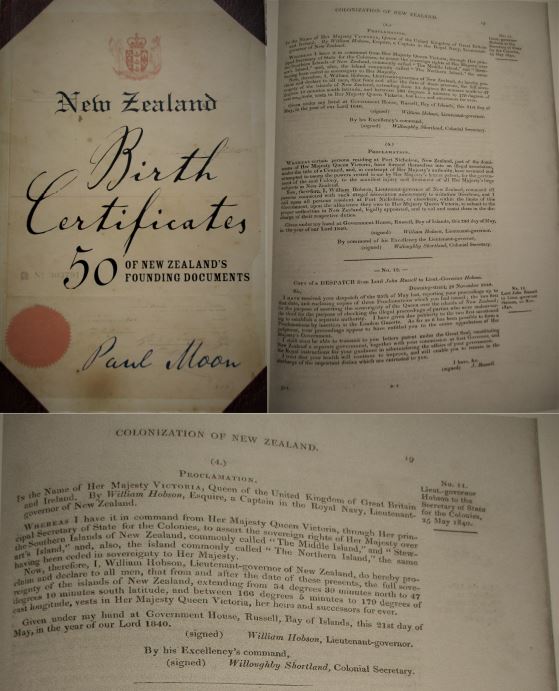

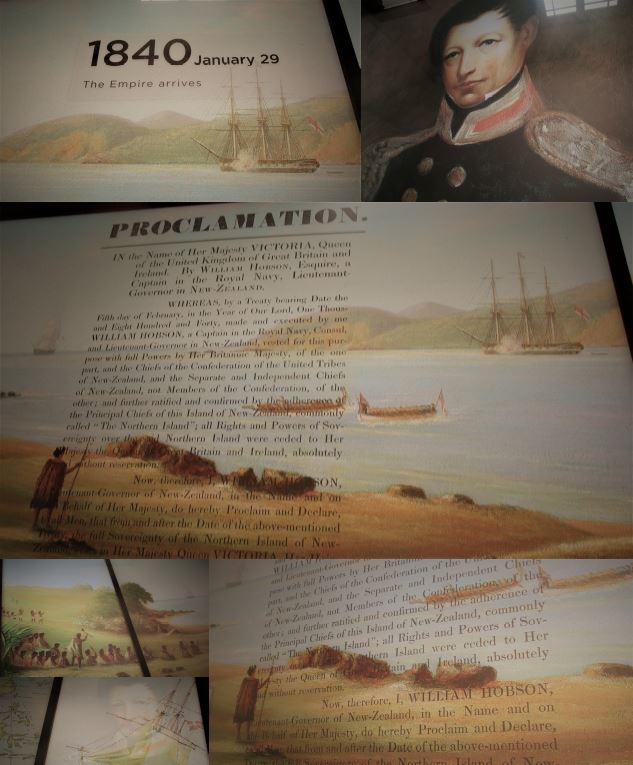

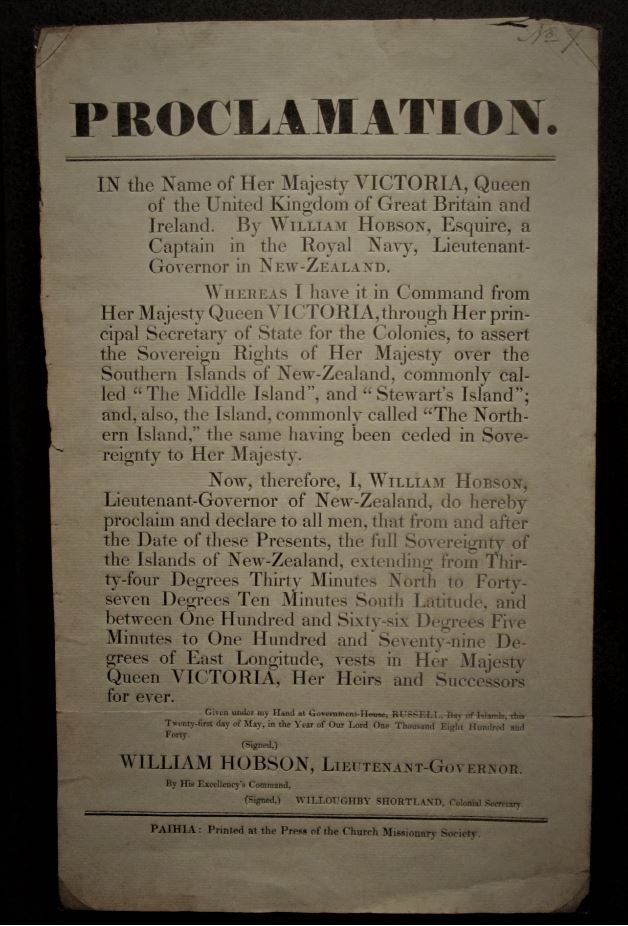

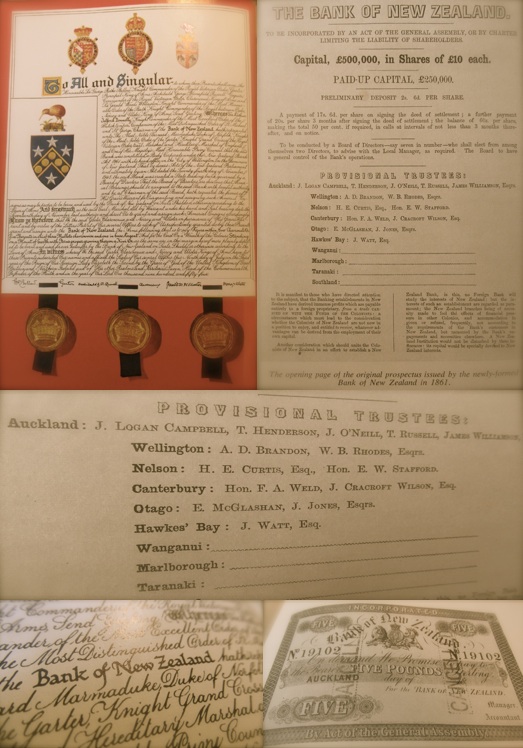

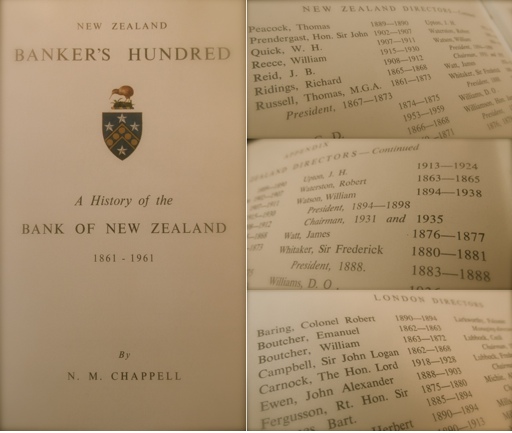

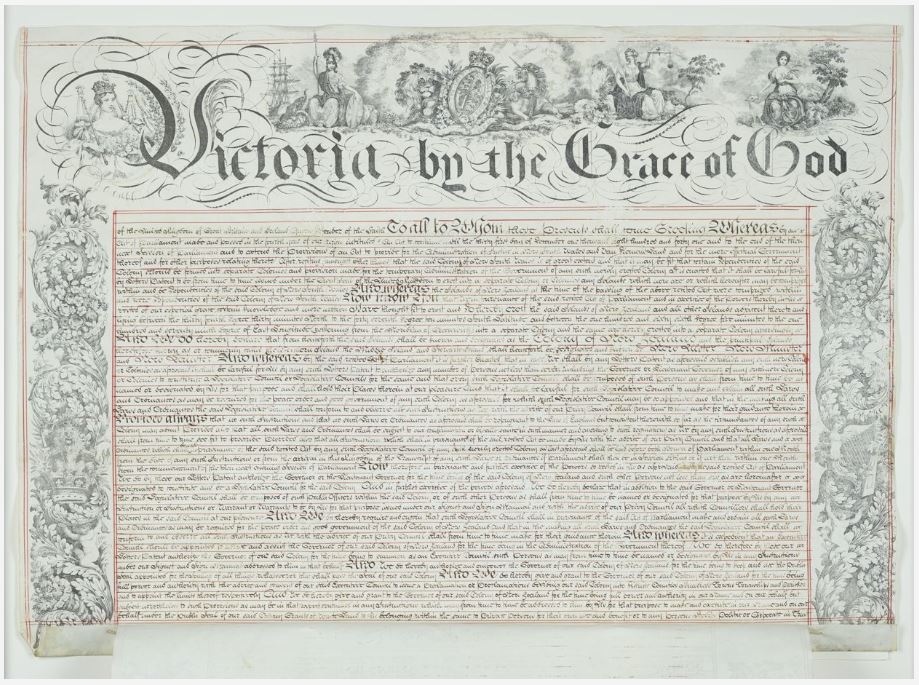

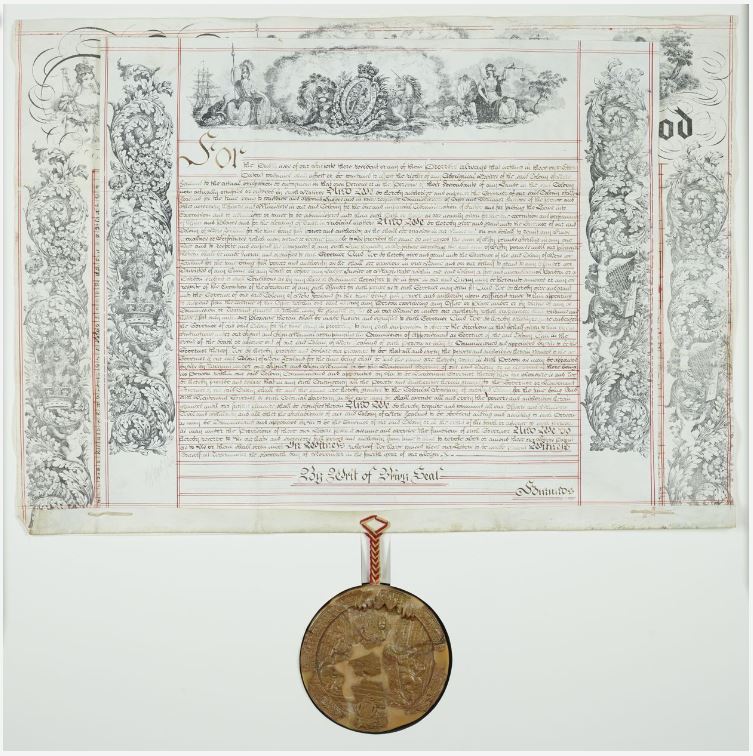

Crucially, when Queen Victoria’s Royal Prerogative Powers were used on three instrumental occasions prior to and after the Waitangi Treaty signings, none of the three legal devices made under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom, mentioned the mode of sovereignty acquisition. The three legal devices were: Letters Patent of Boundary Extension to expand the jurisdiction of New South Wales to envelop the islands of New Zealand on June 15th 1839; Letters Patent of Amended Commission, which appointed New South Wales Governor George Gipps as the first Governor of New Zealand, and appointed Captain William Hobson as Lieutenant Governor over the new dependent colony of New South Wales by Her Majesty’s Command on July 30th 1839; and a Royal Charter for Severance (or Charter of 1840), which was signed by Queen Victoria to establish New Zealand as a separate colony on 16th November 1840.

Thus, the Treaty was omitted from these legal devices. And, by this legal wizardry the islands of New Zealand were for a brief time, a dependent colony of the ‘Land of Oz’.

The ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ began in June 1831, when James Busby outlined a policy he published in England, titled “Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand”, in which the future British Resident wrote his dream job description. As a wannabe British agent, he aspired to have the power to make treaties with Māori. This sketch for a Treaty Theatre Track advanced on October 5th 1831 with a letter signed by 13 rangatira asking King William IV for his protection.

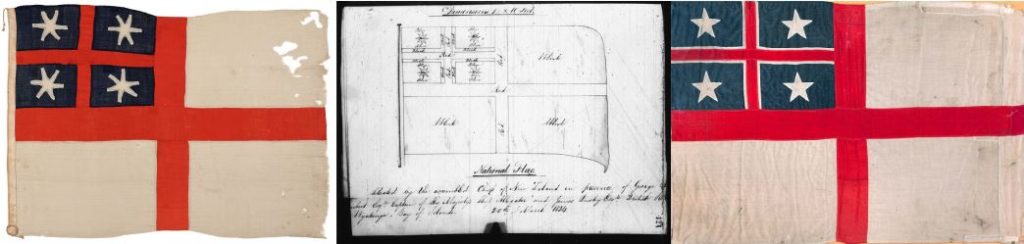

The Treaty Theatre Track took form with the ‘apparent’ joint British Resident-rangatira initiative to reach an ‘agreement’ over a National Flag for Shipping in 1834. Busby’s subsequent goading of Chief Rete soon after should have raised alarm bells.

The British Resident’s pretensions to authority were a thorny matter that needed to be nipped in the bud. Busby had interfered with the logging trade of the rangatira’s hapū (or family group), which led to the precedent-setting punishment that was New Zealand’s first British-inflicted land confiscation.

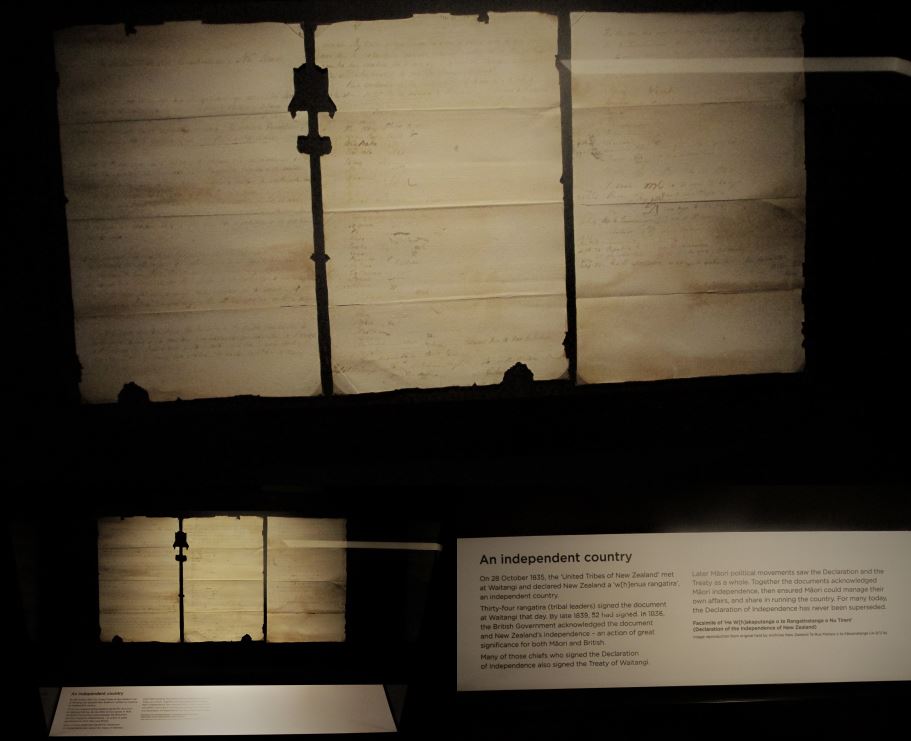

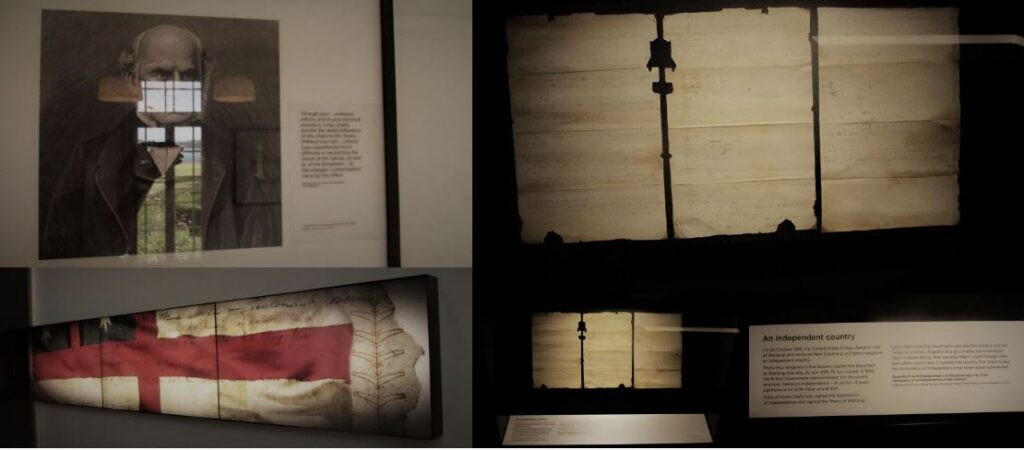

This track to the treaty was further advanced with the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand’, creating the edifice of an ‘independent state’. More Treaty track was laid by Captain William Hobson’s Factory System plan of 1837 which proposed a treaty for settlements, although the plan itself was not implemented.

All of these moves culminated in the 1840 Te Tiriti o Waitangi, accompanied by its evil English language non-identical twin. The Treaty Signing Rituals not only served to defuse Māori resistance by tricking the Treaty Chiefs and Chieftainesses that they would retain their sovereign authority and power, while saving face for the British Parliament, the British Monarch and the British Crown’s fraternal crown twin, the City of London Municipal Corporation.

The incontrovertible fact is that the Waitangi Treaty Signing Rituals were a hostile stage production performed to takeover the Māori nations, or a théâtre usurp d’état. The object itself was a literary device designed to distract from the Colonial Law Track upon which the tenuous claim to sovereign title was first acquired by boundary extension with a Letters Patent and subsequently ratified with a Royal Charter to erect a colony.

This finding means the 1840 compact was a red herring mechanism to sponsor logically fallacious arguments to hook enough Māori, and — subsequently — divide and defeat the tribal race. The intention was to lead its audience to a false conclusion, whom would not comprehend the Waitangi Treaty Theater was, in effect, a simulation produced to create a copy of reality intended to eventually forge subject race pacification during and after the consolidation stage of what was, in fact, the New Zealand Masonic Revolution.

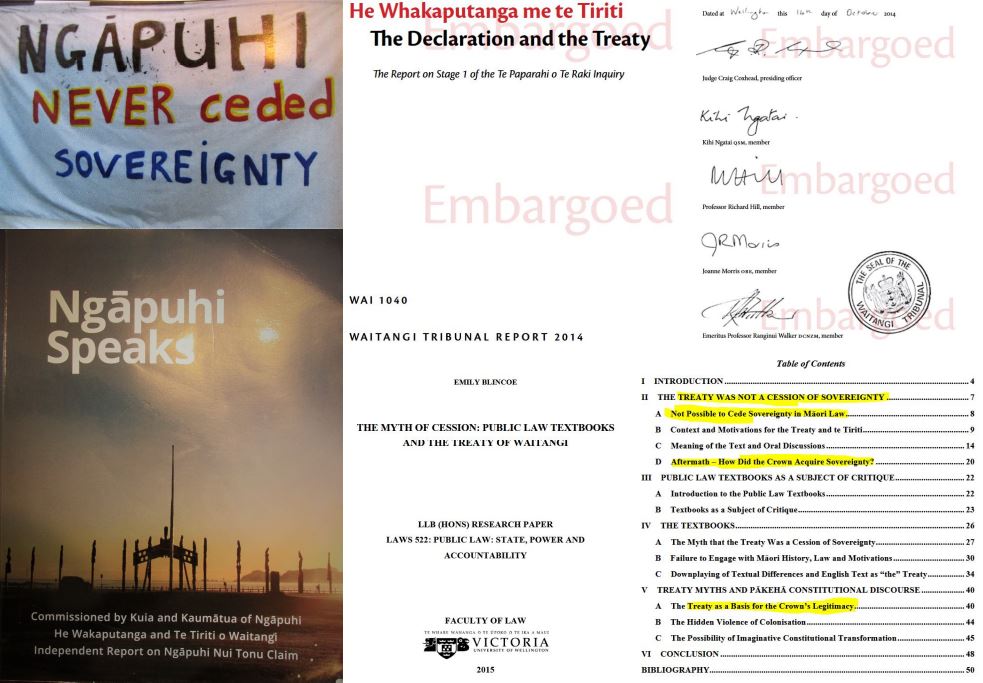

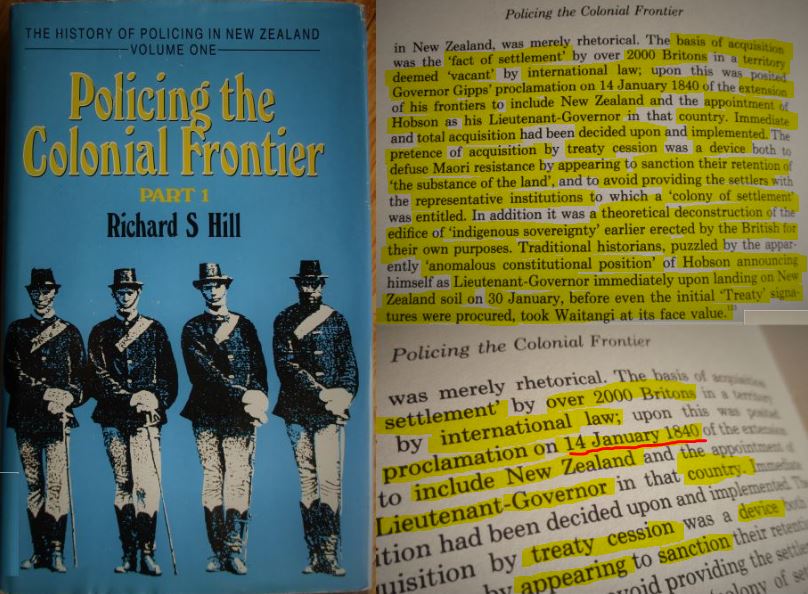

In his 2006 book, Waitangi and Indigenous Rights: Revolution, Law & Legitimation, Emeritus Professor of Law at Auckland University, Jock Brookfield, argued the Treaty signings set in train a revolutionary seizure of power with Captain Hobson’s proclamations of May 21st 1840 — that upended Māori customary law and pulled off “a large scale robbery”. Brookfield asserted it was implausible that Māori agreed to the full transfer of sovereign power that the British Crown claimed in 1840 and subsequently enforced by various acts.

Moreover, the British Crown took from chiefs who did not sign the Treaty, and therefore power was assumed and exerted over those hapū who ceded nothing. The Auckland University professor makes the case that the seizure of power was a silent revolution and legal from the perspective of British law at the time, but a breach of Māori customary law.

In fact, the seizure of power was usurpation since a revolution is the upending of a social order by people already living in the society.

Therefore, the usurpation that occurred in 1839 and 1840 was a usurp d’état rather than a coup d’état, which is a sudden violent seizure of power of a state. Because Māori outnumbered settlers and foreigners by 50 to one in 1840, and because Britain did not have any apparatus in place to sustain a takeover, an attempted coup d’état would have drawn the wrath of Māori and any chance of colonization would likely have gone to the French. Similarly, concocting a false flag coup d’état, such as assassinating a Māori chief, with blame cast on the French would have been more complicated, highly risky and likely quickly unravel.

But, the British takeover of New Zealand still required trickery.

More precisely, a théâtre usurp d’état was opted for, in which a cliqué formed to orchestrate, in essence, a Treaty Theatre Production Company that would script the trickery, hire a theatrical troupe and commandeer improvisational actors to assist in the mission to persuade.

Meanwhile, the legal mechanics of the heist occurred by a parallel track.

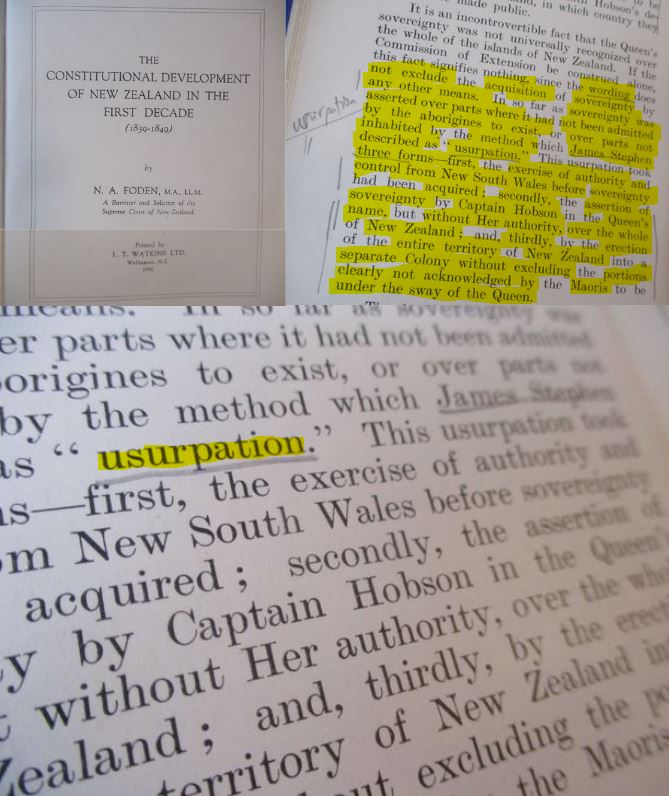

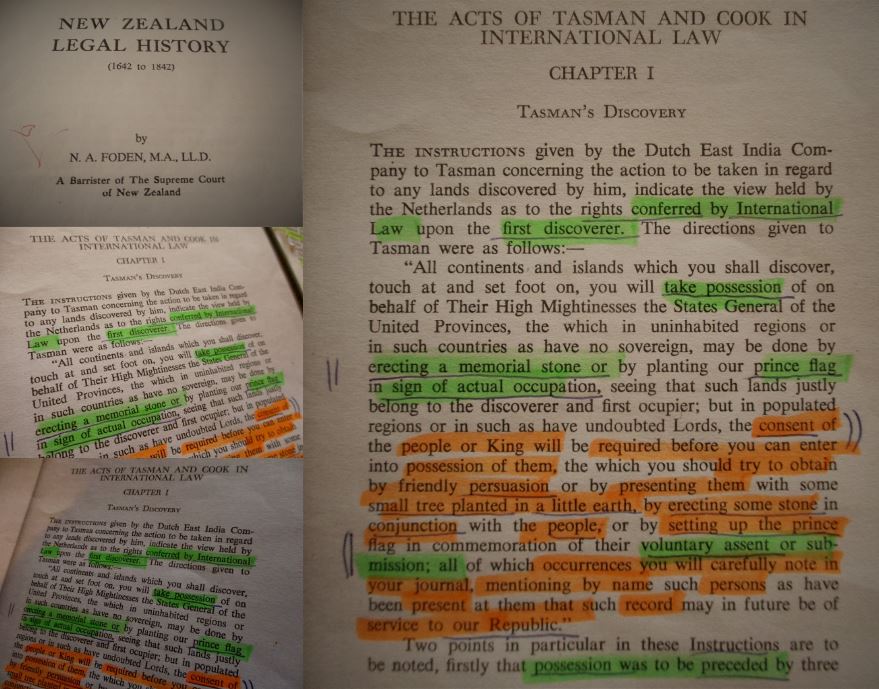

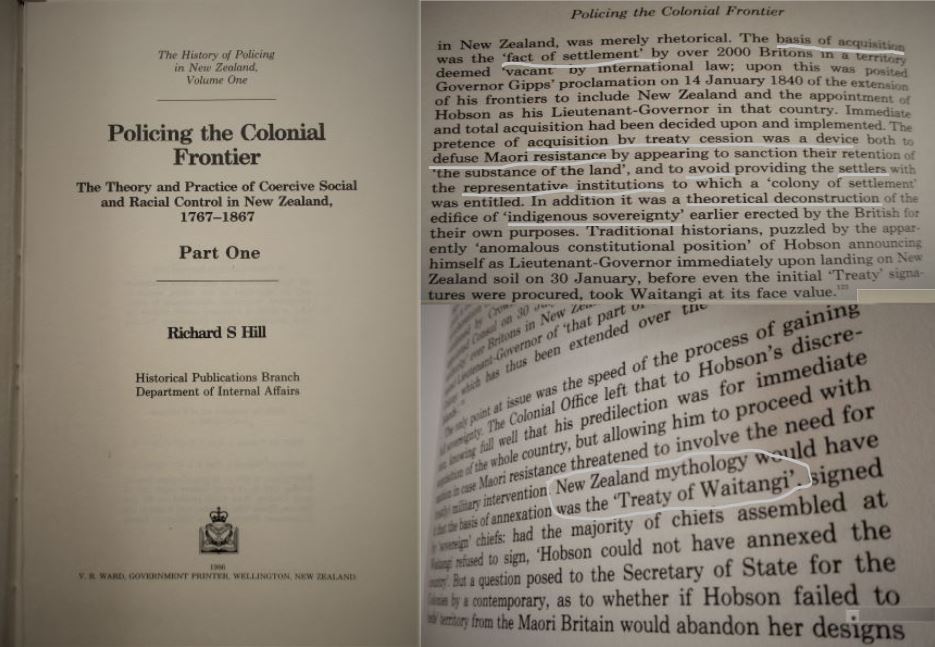

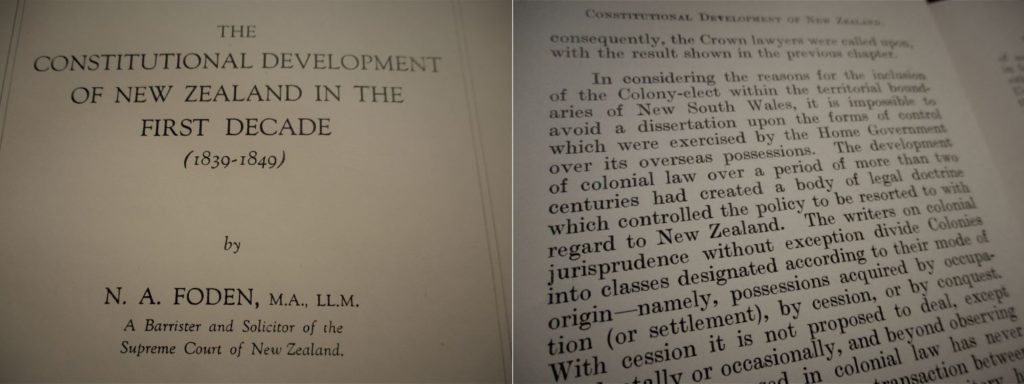

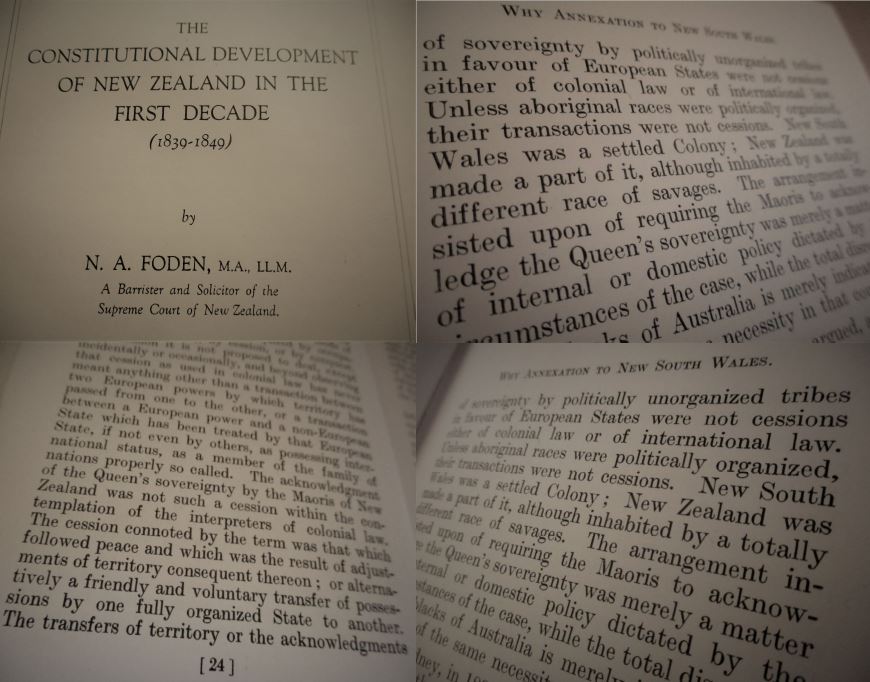

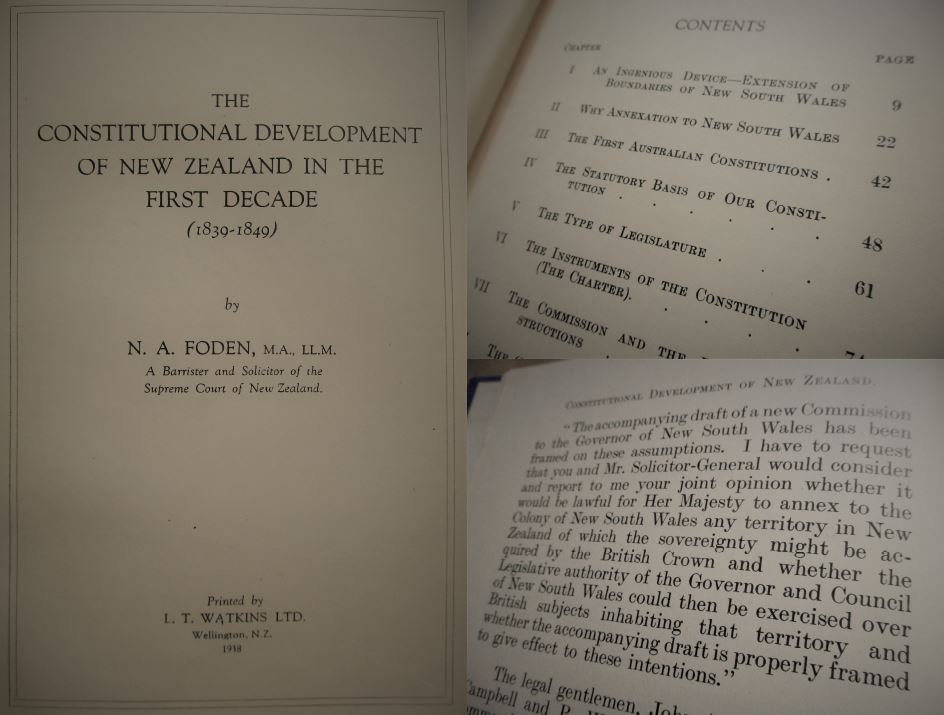

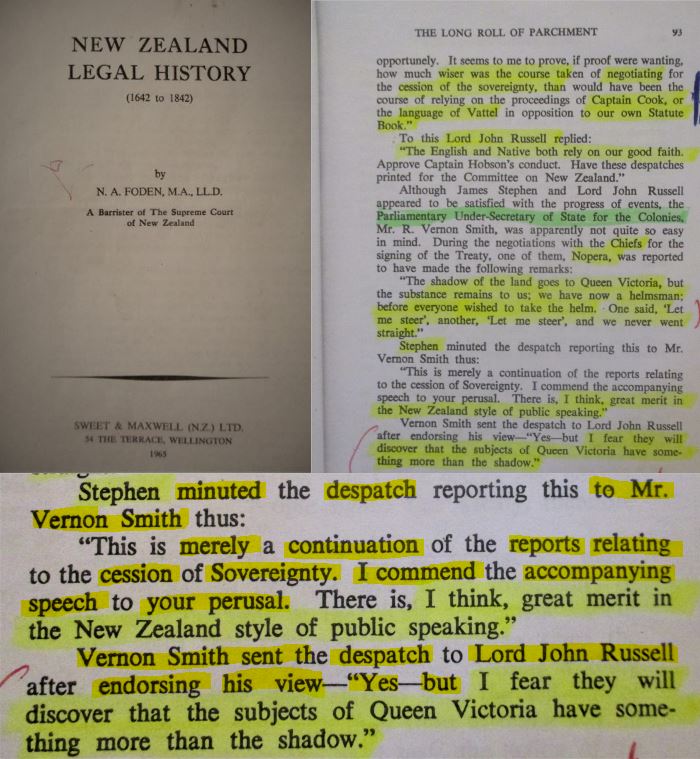

This parallel track was detected by Norman Arthur Foden, whose 1938 work — The Constitutional Development of New Zealand in the First Decade (1839-1849) — proved that New Zealand was acquired by the British Empire on the basis of occupation on June 15th 1839, when the South Pacific archipelago became a dependent colony of New South Wales. By means of a Letter Patent device to erect a dependent colony, the British Crown adopted the unauthorized British settlements, and therefore sovereignty was wrested by usurpation through the Colonial Law Track legal moves.

Although Foden — who was a barrister and solicitor with the Supreme Court of New Zealand — did not name a parallel Colonial Law Track as such, he identified the legal moves that were consistent with English Constitutional Law. The legislation for the acquisition of the Colony made it legal for the Monarch to sign the Royal Charter of New Zealand on November 16 1840. The accompanying Letters Patent device to erect a separate colony was timed to occur after the treaty sheets arrived in London — to make it appear the Treaty was the means by which sovereignty was acquired. Once Queen Victoria’s Letter Patent of Severance and the Royal Charter of New Zealand were ratified with the Privy Seal of the United Kingdom, the British Crown’s title became unchallengeable by British subjects, under English Constitutional Law, and was recognized by other nations under International Law.

This re-framing of what occurred in 1839 and 1840 does not mean a revolutionary dynamic was absent. Since a seizure of power occurred in 1839-1840, power crime theory provides a critical lens to view these historical events, which occurred in haste.

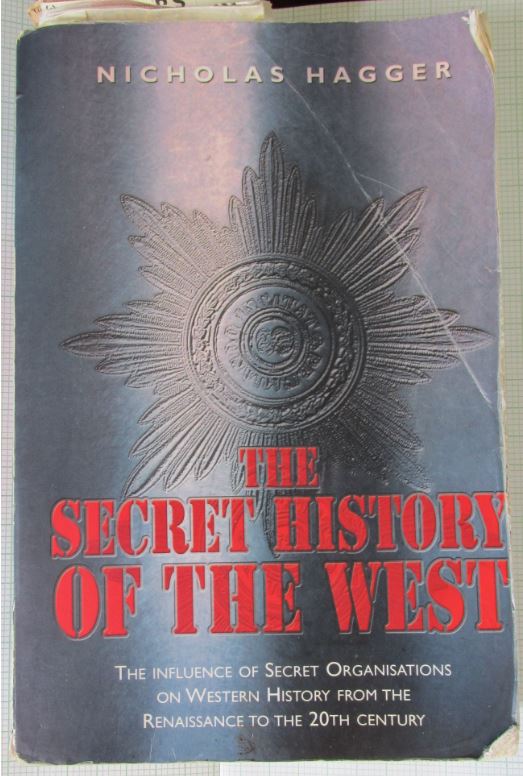

In his epic 2005 study, The Secret History of the West, English historian Nicholas Hagger modelled the patterns of revolutions, how subversive secret societies plotted them and the reasons for the subterfuge. Drawing upon 550 years of revolutions, Hagger shows that all revolutions have four distinct stages with four archetypal characters. An Occult Idealist expresses a heretical vision, which is given an intellectual expression by an Intellectual Interpreter. A Political Actor takes this blueprint into the political realm, where it is corrupted by the ruling regime, and led by a Consolidator, those secret groups most invested in the occult vision plot physical repression to realize their utopia.

Since a seizure of power occurred in 1839-1840, power crime theory provides a critical lens to view these historical events, which occurred in haste. Élite criminal groups exploit the speed of high-velocity engineered events to distort perceptions about the facts of events that overtake “low velocity political deliberation and public accountability”, as Monash University senior lecturer of public international law Eric Wilson has explained. In the process, the splicing of space and time and kinetic image sequences depicted in newsreel frames mask the speed-politics with a copy of reality, thereby rendering the in-built power crimes invisible. Although Wilson’s exploration of power crimes is located in a modern context of violent coups d’état committed with scripted false-flag cover-up scenarios, his modelling is applicable to the Waitangi théâtre usurp d’état. Since the mission to Treat with ‘the natives’ was intended as an epic heist of sovereignty over Māori, whether they signed or not, the witting players of Waitangi Treaty Theater Production were acting as a criminal group in breach of Māori customary law.

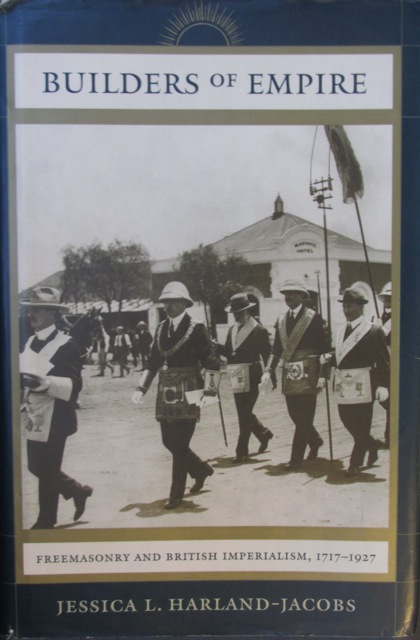

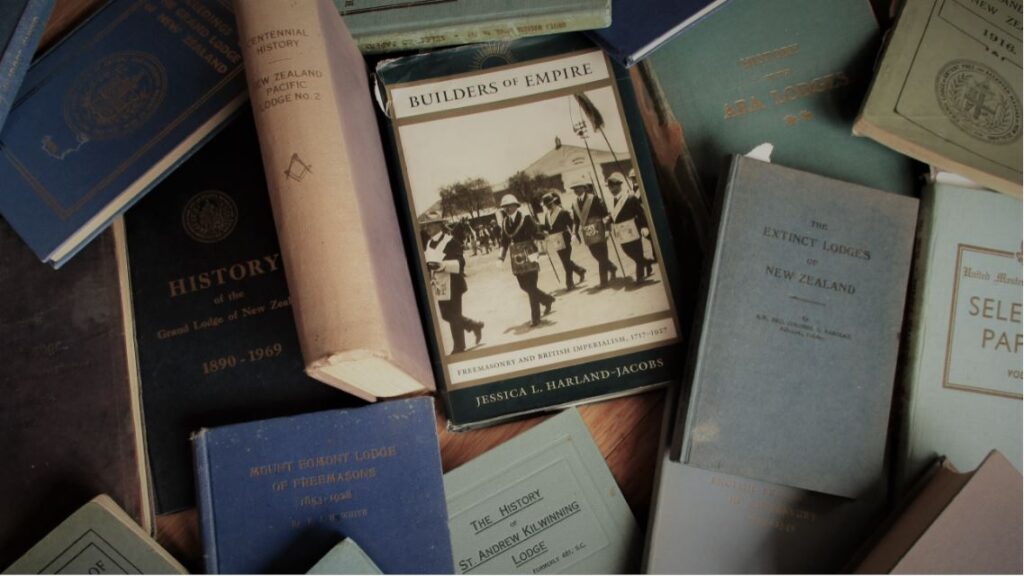

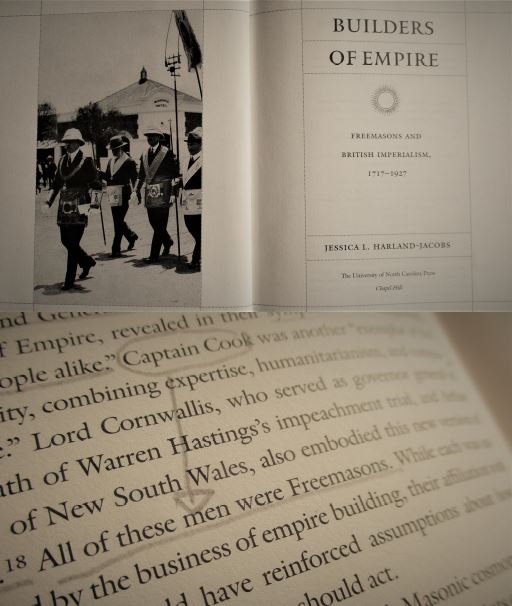

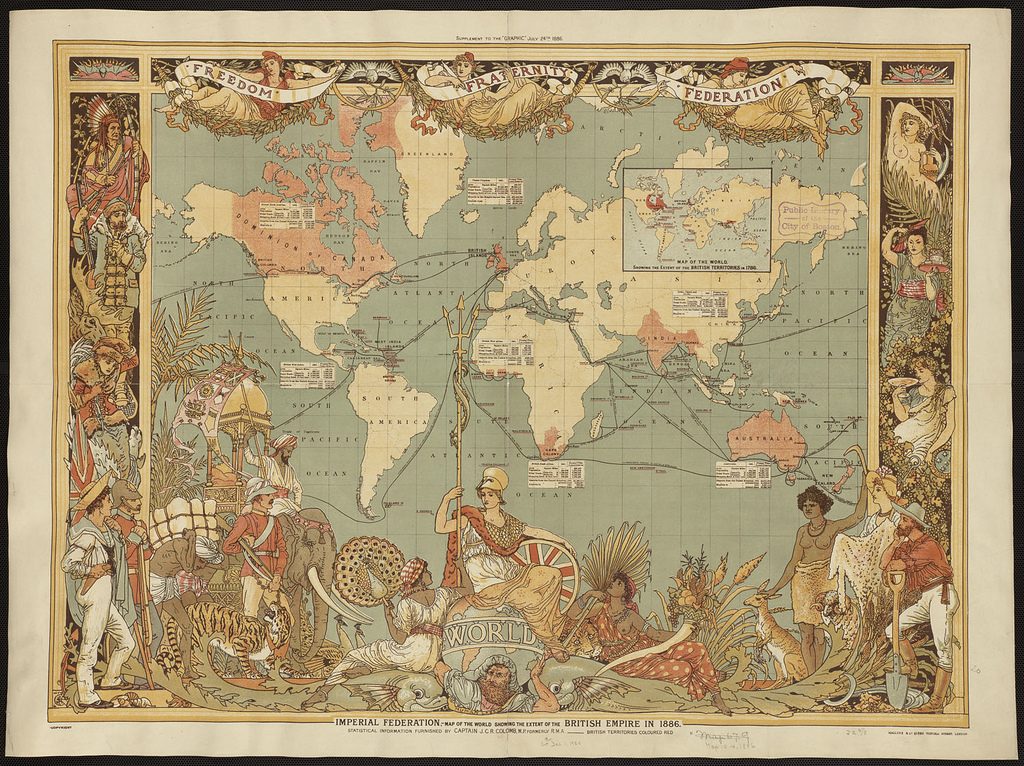

This historic travelling theatre production is perhaps best viewed as a Masonic imperialist expression of applied ‘Orientialism’ masked by a humanitarian mission to formalize the mechanisms wherein New Zealand would be coded, chronicled and conquered under a British banner. The primary secret mechanism by which the British Empire spread throughout the ‘New World’ was through the subversive secret society of Freemasonry. In turn, Freemasonry was spread mostly through the military regiments, including the navy, as Jessica Harlands-Jacobs stated in her book, Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927.

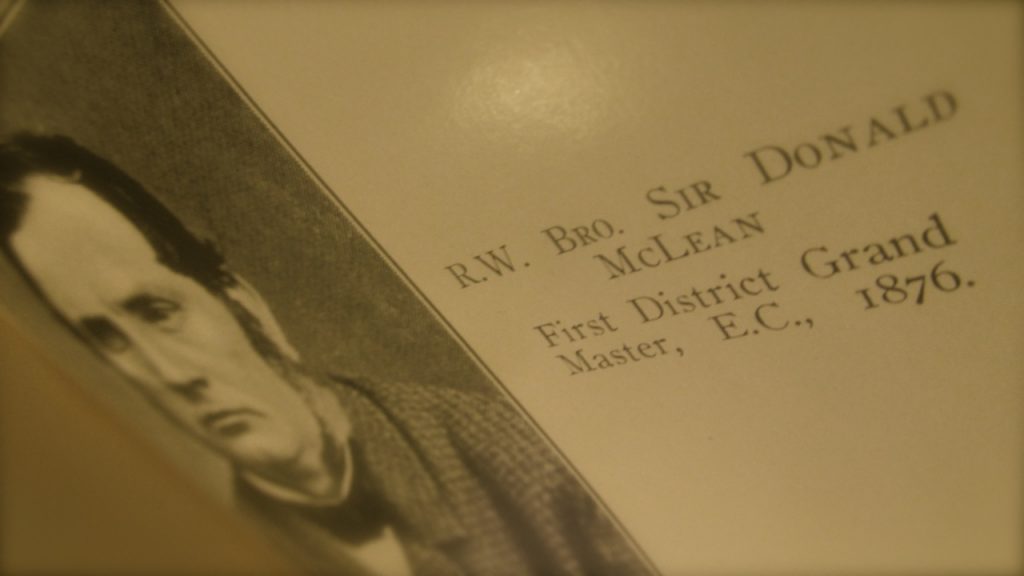

The Masonic lodges created a private model, mechanism and mask for public affairs that multiplied by warranted dispensations, or licensed charters, to operate a secret membership based on a closed system of constitutional government, whose key oath was to always follow orders from above. At its core, the Masonic Lodge System served the ideological function of activation to unite against a common enemy with a subversive private parallel political, commercial, martial and cultural structure that spread from the ‘Old World’ to operate in new ‘Masonic jurisdictions’ of the ‘New World’ for its re-ordering either by Masonic Capitalism, Masonic Socialism, or Masonic Communism. This meant Freemasonry became a key conduit for the marketing ideas of European superiority among an international network of loyal men whom forged the capacity to act as a subversive confederacy to undermine aboriginal and indigenous nations for their subjugation, de-tribalization or extermination — depending on the circumstances.

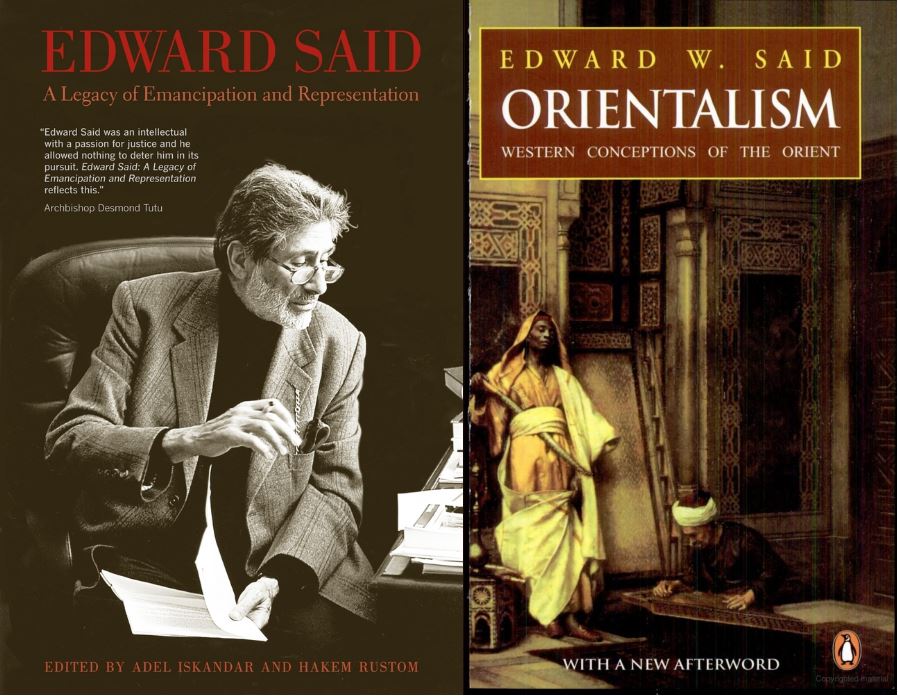

In his seminal 1979 book, Orientalism, Edward Said, observed that events in the Orient of the Near, Middle and Far East, North Africa and the ‘New World’ were repeatedly turned into theatre to save the events from oblivion by ‘Orientalists’, or Europeans aiding the categorizing, Christianizing and colonizing projects. The modus operandi of the Orientalist, was to consult ‘the natives’ for a text whose usefulness was not to aboriginal and indigenous peoples; a practice that stretched back to at least the second century B.C.

Said summarized Orientalism’s tropes that condescendingly cast aboriginal and indigenous peoples of the Orient and consequently the ‘New World’ as being depraved, childlike, irrational, barbaric savage natives, whom were considered inveterate liars, gullible, devoid of energy and initiative. The Western habit for domination, restructuring and having authority over the Orient, involved surveying a civilization from its origins, its prime and its decline to gain and possess knowledge of a civilization, with the result that such surveys could translate into dominating and holding authority over a civilization and denying such a people any substantial autonomy. For example, deviations from behaviours expected of ‘subject races’ were considered unnatural, promiscuous or criminal since the Orientalist paradigm viewed ‘Orientals’ as backward in comparison to the ‘self-evident truth’ of European superiority.

The Orientialist tropes were weaponized as a technique to faster, friendly terms with ‘the natives’, while extracting the wealth of resources, exploiting the labour of aboriginal and indigenous peoples and dispossessing their ‘wild savages’ of lands. In these stealthy ways, occupied lands became a laboratory, a theatre and the province for appropriation of knowledge in projects of subject race pacification for more profitable sequences of information to produce wealth, power and control.

Poignantly, Said contended that it is crucial to examine European recordings of the Orient as a discourse in order to comprehend the enormously systematic discipline, management and reproduction of the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period, from 1800A.D. onward. Fascinatingly, Said noted that though the French and British were at times hostile rivals with great empires, they were at other times, allies and partners, whom also shared land, profit, or rule and crucially intellectual power, in effect, through creating a library or archive.

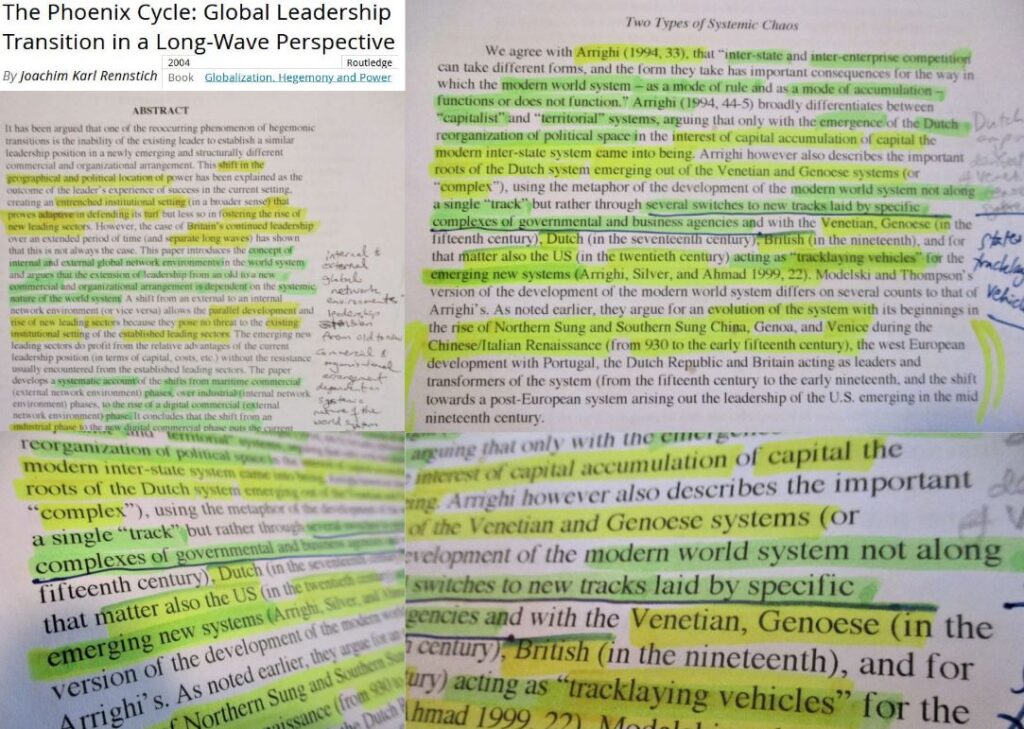

To this end, I — Doctor Thunk Evil Without Being Evil — have applied Giovanni Arrighi’s metaphor of ‘track-laying vehicles’ in state formation from his 1994 book, The Long Twentieth Century: Money Power, and the Origins of Our Times that Joachim Karl Rennstich drew upon in his paper, “The Phoenix Cycle: Global Leadership Transition in a Long-Wave Perspective”. Arrighi described how the modern world system was constructed by public state and private enterprise complexes that activated ‘switches’ to new ‘tracks’. Rivalrous major powers invent new tricks to gain supremacy. With this triangulated approach of empire and power crime revolutionary theories, I present a model with sharply focused lenses to reveal the internal revolutionary logic, dynamism and cast of conspiratorial characters underpinning the Waitangi théâtre usurp d’état.

Treaty Theatre Track – From Busby’s Dream Job to Te Tiriti o Waitangi 1840

In his 2014 book, Beyond the Imperial Frontier: The Contest for Colonial New Zealand, historian Vincent O’Malley stated, “Busby’s role as an agent of socio-cultural and political change among the northern tribes” had for a long-time escaped the scrutiny that his machinations deserved. In the chapter “Manufacturing Chiefly Consent? James Busby and the Role of Rangatira in the Early Colonial Era”, O’Malley wrote:

“from the outset Busby had set about challenging existing northern leadership and governance structures in his efforts to manufacture a more centralised form of government, open to his ready manipulation on behalf of the British Crown.” [2]

Tellingly, in a letter to his brother, Alexander, James Busby explained he intended to gain “almost entire authority over the Northern part of the island” by developing ties with rangatira — as O’Malley recounted.

The British Resident was likely advised by the Protestant missionaries of the Church Missionary Society that his objective to construct a Confederacy would only succeed if the chiefs believed they were authors of such collective action — as Samuel D. Carpenter found his 2009 report — “Te Wiremu, Te Puhipi, He Wakaputanga Me Te Tiriti Henry Williams, James Busby, A Declaration and The Treaty” commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal.[3]

Busby assumed Māori had never conceived the ‘idea of confederating for any national purpose’ and he believed New Zealand to be territories of tribes whose independent-minded chiefs could be lured into forming the appearance of a national government.

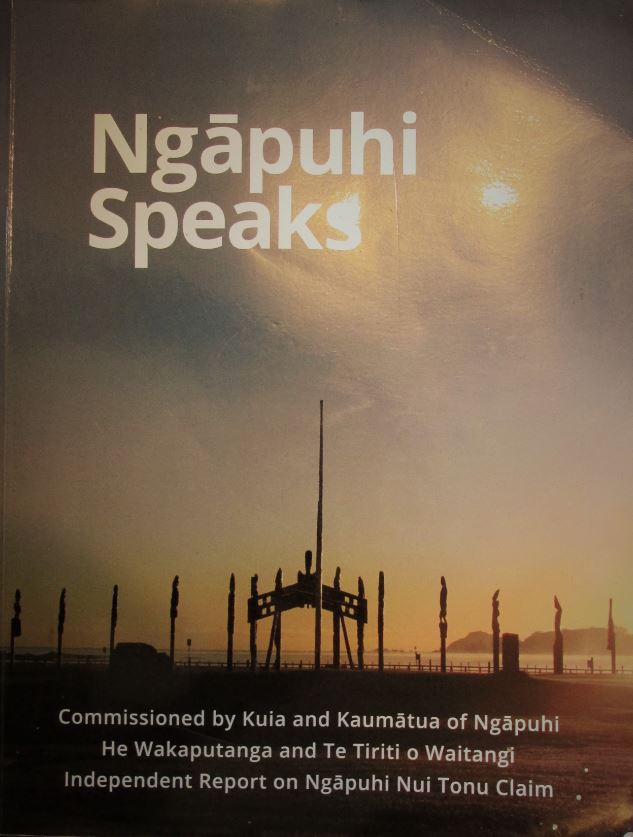

In a field-study commissioned by Kuia and Kaumātua of Ngāpuhi, Ngāpuhi Speaks, it was asserted that the Northern Alliance chiefs had maintained a custom of gathering known as Te Wakaminenga that dated back to 1808, following the Ngāti Whātua tribe’s victory over Ngāpuhi in the Northland battle of Moremonui at Maunganui Bluff, in 1807, at the beginning of the Musket Wars (1806-1845). Other issues arising from European contact were also discussed at the Te Wakaminenga meetings, including international trade, land loss and challenges to tikanga, or cultural practices. These Te Wakaminenga gatherings, which are referenced in Article One of the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835, did not usurp or over-ride hapū autonomy, and if there was consensus reached, the agreements were not binding — the ground-breaking Ngāpuhi Speaks study found.[4]

In June 1831, James Busby outlined a policy published in England as a “Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand”, in which he wrote a job description for a magistrate to live among Māori. Busby proposed to acquire a modest piece of land by contracting with the chiefs, and to be empowered to make treaties with rangatira, and to set up a trade prohibition to exclude Europeans from such a district.[5]

Later in 1831, a letter of petition that was signed by 13 Māori chiefs by way of moko drawings, was sent to King William IV asking for the King’s protection.[6] The petition of October 5 1831, which was likely drafted by William Yate and Eruera Pare Hongi, has the clear hand of a Protestant missionary’s agenda, specifically Reverend Henry Williams. In September 1831, a rumour had spread that a French ship was coming to invade and evidently caused much alarm in the Bay of Islands, and several rangatira approached Reverend Williams to seek protection from King William IV. A French corvette, La Favorite, arrived on October 3. The ‘Letter to King William IV’ emphasized the concern of Māori chiefs who had been manipulated into thinking ‘the Tribe of Marion’ (the French) was at hand, coming to take away their land.[7]

In an oral and traditional history report, “He Rangi Mauroa Ao te Pö: Melodies Eternally New”, Associate Professor Manuka Henare, Dr Angela Middleton and Dr Adrienne Puckey state that ‘Northern Māori oral tradition … does not record any alarmist tendency from among Māori about French intentions to take over the country’.[8] This 600-page report, which was received by the Waitangi Tribunal in 2013, frames this event as a continuation of ‘a dialogue of equals’, in this case between the thirteen signatories — Wharerahi and Rewa (Patukeha), Te Haara, Patuone and Waka Nene (Ngāti Hao), Kekeao, Titore, Tamoranga, Matangi, Ripe, Atuahaere, Moetara and Taunui — and King William IV.

However, this ‘dialogue of equals’ is bunk rhetoric that short-fuses critical thinking brain circuitry.

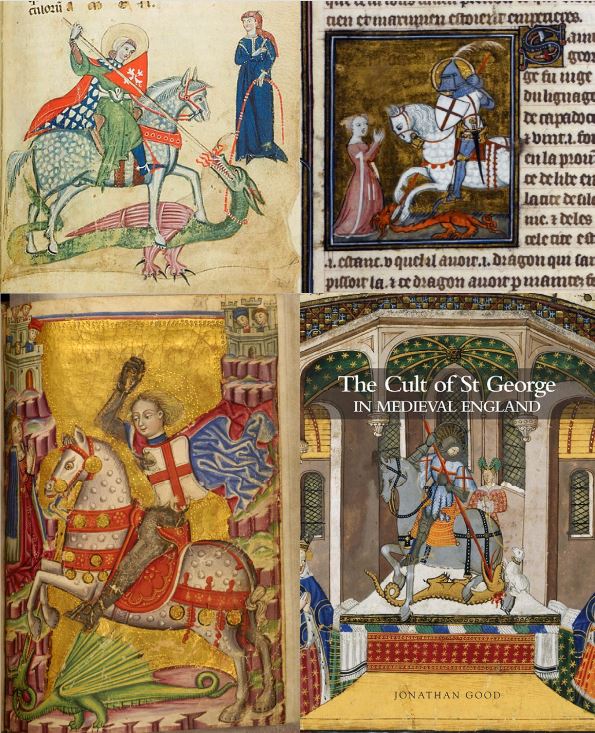

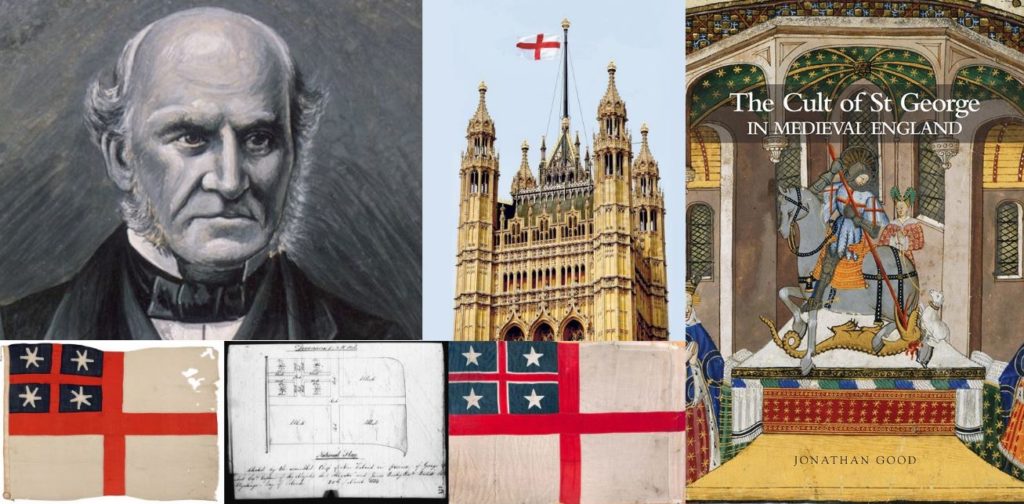

For one thing, William IV was the Sovereign Head of the English Order of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, which is England’s most prestigious dynastic order. The Order of the Garter was founded in 1348, by King Edward the Third, eleven years into the First Hundred Years’ War fought over the Kingdom of France, and marked the decline of feudalism and the rise of nationalism and the commercial revolution, which was enabled by the credit revolution innovated by the Knights Templars. The core of Western Civilization was conquered by an imperialist state: by Henry V’s England around 1420 resulting in chivalry being circumvented with commercial capitalism. This Order of the Garter features the St George’s Cross, St George and the Dragon, and not surprisingly, given the Cult of St George, this legendary character is the patron of all knighthoods, according to Orders and Decorations, written by Václav Měřička.[9] Indeed, new knights are often announced on St George’s Day. The Royal Monarch always becomes Sovereign Head of the Order upon ascension to the British Throne, which is located in the British House of Lords in Westminster City.

Meanwhile, in a letter dated November 10th 1831 that Busby wrote from London to his brother, New Zealand’s future British Resident proposed that he become “the authorised agent of the British Govt. in treating with the Native Chiefs [of New Zealand] for the Mutual protection of their own people and of the Europeans…”, and in doing so, signaled that through his agency, the Treaty Track could advance.

In March 1832, Busby sent his Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies of Britain, Lord Viscount Goderich, in which he hinted at French designs to takeover New Zealand and also of Russian interest in the South Pacific archipelago. With the support of missionaries, and the favourable impressions he made on the Colonial Office, and helped along with a tasty bribe of 40 bottles of wine produced at his vineyard in New South Wales — Busby was awarded the post as British Resident.[10]

Thus, the appointment of New Zealand’s first British Official occurred through the grand imperial tradition of bribery, fear stoking about imperial rivals and missionary testimonials to pass the political hygiene test.

Busby would be afforded the protection from the Vice-Admiral of the Indian Squadron, Sir John Gore, who was ordered to deploy ships to visit principal harbours of New Zealand as frequently as possible.[11] This protection was symbolic, since the ships would simply act as a presence to remind all foreigners that the British Royal Navy were the water police of a transmarine empire.

The response attributed to King William’s ‘mind’ came through a letter written by the high-ranking Secretary of State, Lord Viscount Goderich, who feigned to accept the rangatira communiqué of “friendship and alliance with Great Britain”. This letter carried the same date, 14 June 1832, as Goderich’s instructions for the British Residency appointment. Busby had suggested an audience with the King before his departure to elevate his esteem in the eyes of the chiefs. However, such a meeting risked embroiling the British Monarchy in the machinations Busby would author.

This idea was rebuffed.

The logic of power suggests it would not suit the British Empire’s long-game to have the King so directly endorse their point-man for reeling in their big catch, with so little expended in fishing tackle and bait. It was Goderich’s letter that Busby read on his arrival to a gathered audience of rangatira.

After all, rangatira had been led to believe that the encounters between chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato with King George IV in 1820 signified the beginning of this ‘dialogue of equals’, rather than of two fish taking the bait on two hooks of a very long imperial line. Chief Hika attempted to forge an empire by escalating the Musket Wars upon his return by trading the gifts he and his nephew Waikato had received in London, for muskets, gunpowder and cash.

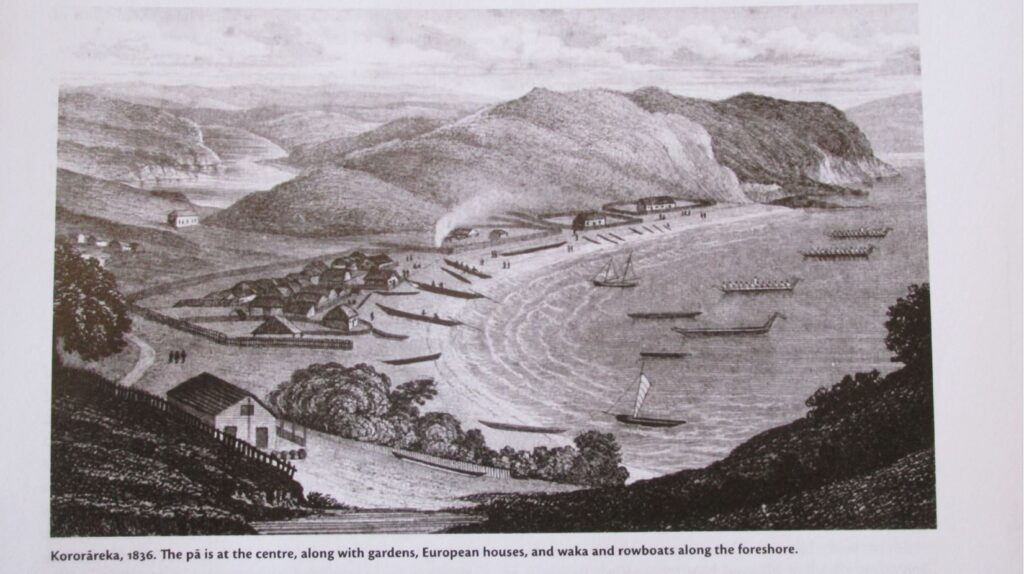

By the time of his arrival in Peiwhairangi, the Bay of Islands, on May 5th 1833, Busby “resolved to bend the whole strength of my mind to effect this object” toward a Confederation of Chiefs.[12] After twelve days of badly behaved weather, Busby came ashore and read Goderich’s letter to an audience of 22 high-ranking rangatira and more than 600 other Māori.

By exquisite serendipity, New Zealand’s first British official had learned of the woes of Māori shipping before departing for New Zealand at Port Jackson, Sydney, from a ship owner, Joseph Hickey Grose, who sought his help to get his impounded ship registered. Customs Authorities had a ship, named the New Zealander, impounded in January 1833 for failure to be registered as a trading vessel and to fly a national flag.[13] This incident followed the November 1830 impounding of the Sir George Murray, with the Hokianga high chiefs and part-owners, Patuone and Te Taonui, on board.[14] Because New Zealand had become a foreign territory to the Colony of New South Wales in 1823, and was not a recognized power, the aboriginal and indigenous-owned vessels could only be placed under the flag of a ‘friendly power’ once all the signatory chiefs’ marks were gathered, and provided, the ships were three-quarters crewed by ‘natives’ — then such ships could ply their wares under the Reciprocity Act.[15]

As the Waitangi Tribunal noted in its 2014 report, “He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti’:

“Busby astutely recognised that the issue provided an opportunity for him to draw the chiefs – who would probably never have contemplated ‘confederating for any national purpose’ – into working in concert. After his arrival in New Zealand, therefore, and a few days even before he was presented to Bay of Islands Maori, he outlined his plans to the Secretary of State of War and the Colonies, for the rangatira to come together and choose a national flag for New Zealand-built ships. He himself would undertake to certify the chiefs’ registration of the ships, but only if two-thirds of them agreed upon a flag design and petitioned King William to have it respected. Through this precedent he hoped the chiefs would ‘consent that they will henceforth act in a collective capacity in all future negotiations with me’, with the ensuing ‘confederation of chiefs’ providing the basis for an established Government’.”[16]

Evidently, Māori maritime commerce needed saving from the maw of the British Dragon of Maritime Traffic Infringements and it was lucky that British Resident James Busby just happened to ‘hear’ of its peril while at Port Jackson. After this serendipitous encounter, Busby exploited the matter to get a national flag for Māori shipping as a cause célèbre mechanism to weld rangatira into a formalized collective federation of national purpose.

To this end, Busby, in essence, cast himself as the heroic protagonist in the Cult of St George. The popular legend of St George valourizes his role as a soldier who saved a princess from the maw of a hungry dragon that won the customary right to eat sheep and children. The princess had been drawn in a ballot for sacrifice. With exquisite synchronicity, St George the Christian Knight just happened to be passing through the terrible scene. Saint George astutely saw an opportunity to expand the Church’s franchise and offered to save the princess on condition that the traumatized people convert to Christianity. In keeping with the legend of St George, Busby only did so by extracting a ‘pound of flesh’ from ‘the Natives’.

In January 1834, Busby sent three flag designs, drawn by the Church Missionary Society Reverend Henry Williams, to Sydney to be produced as prototypes.

A hui was hastily called for March 20th 1834 to convene on the front-lawn at Busby’s house at Waitangi, with about 750 Māori in attendance.[17] Busby’s design was to subvert Māori agency without the rangatira knowing the track he was leading them down. Embedded in Busby’s machinations were the gaining of submission of 26 selected principle chiefs, whom he lured to prostrate themselves to reach the exclusive cordoned off area to make their selections, by crawling under a British shipping rope inside a white make-shift ‘tent’ made of sails.[18]

Busby called the chiefs by name, whom included Waikato who had met King George IV, along with Hone Heke who had not met a British King, thereby creating a division “between the noblesse and the canaille (or common) of New Zealand … [causing] … no small discontent of the excluded”, as William Barrett Marshall recounted in his 1836 book, A Personal Narrative of Two Visits to New Zealand in His Majesty’s Ship, Alligator, A.D. 1834.

The chiefs were baffled by Busby’s vote casting process to choose a shipping flag in 1834, as the Waitangi Tribunal in 2014 reported.

At this point, a servant of the missionaries, Eruera Pare, pressed each chief to make a choice and by this coercive method, he was able to tally up the score — according to Von Huegel’s account. The rangatira were indifferent to what was on offer. According to Busby’s own muddled speech, the rangatira were being pushed to make their preference while at the same time they were to confer with the chiefs in other parts of the country, “so that your decision would be the decision of the majority.”[21]

An observer, the Austrian Baron Karl von Huegel, who had come ashore from a Royal Navy ship named after a species of tropical reptile, HMS Alligator, noted that some chiefs queried the logic of these proceedings. On the one hand, the chiefs reasoned, King William was said to be extending his friendship, while on the other hand they were being told the King’s men would seize their ships if they did not accede to a flag.[19] Von Huegel recounted that the first three chiefs each chose a different flag, while the remaining chiefs, “did not care which flag was chosen”.[20]

Twenty-eight votes were cast, with twelve votes taken for the chosen flag, ten for the next choice and six for the third-place flag. Two chiefs abstained, “apparently apprehensive lest under this ceremony lay hidden some sinister design on our parts”, as Marshall described.[22]Marshall observed that “freedom of debate” was discouraged, since Busby invited no discussion, and he claimed a friend, called Chief Hau, evidently asked Marshall what flag was his preference. Hau subsequently voted for Marshall’s preferred flag design, with the St George’s Cross on it and apparently Hau canvassed other chiefs for their votes also. The new Te Kara flag, complete with the St George’s Cross motif, was raised on a poll next to a taller flagstaff flying the Union Jack, and a 21-gun salute fired from the HMS Alligator followed the vote[23].

The 21-gun salute was the traditional pomp to mark a sovereign and on this occasion, evidently to construct the illusion that the British had recognized the islands of New Zealand as a state.

Forebodingly for Māori, Busby invited about 50 European guests into his Residency for a meal, while his Māori guests were served outside with a ‘meal’ of ‘stir-about’, which was a thin paste of flour and water. Busby had deliberately under-catered to discourage Māori from turning up in large numbers and had also sought to place his aboriginal and indigenous guests in a lower status by excluding them from his table. By serving them what was fed to prisoners and the homeless in England, or what was, essentially, children’s glue as food, these insults demonstrated Busby’s machinations. The land-rich rangatira were tricked into participating in a precedent-setting Westminster Parliamentary-style of voting, to select a flag design out of a slim set of three choices.

While the Europeans were dining, rangatira performed fiery speeches outside. Chief Kiwikiwi spoke:

“How have we come into this situation of having to hoist a flag on our boats to ensure our own safety? It is through our own fault that we have to do it, if we had been more united among ourselves, if we had had no enmity of one horde against another, we would have been able to oppose their landing.”[24]

With such exquisite serendipity, and by a narrow margin, enough of Busby’s selected chiefs just happened to choose the one with the St George’s cross on it, the very same cross on the Church Missionary Society flag and which appears on the flag of England. Busby gained their conversion to the cult of British Maritime Law, with their ascent to the adoption of a national flag, complete with the red St George’s Cross motif for abundant replication and a shipping register to entangle Māori maritime commerce. This ‘winner’ only occurred after the chiefs were pressed to pick a preference. The firing of the 21 gun salute from HMS Alligator was theatrics and the dirty details of this episode in gaming Māori were excluded from Busby’s report.

The chiefs’ ‘choice’ gets more curious when it is learned that the Templar Knights adopted the Red Cross in 1145, and French troops used it during the Third Crusade or the Kings’ Crusade, that was co-sponsored by Phillip II of France and Henry II of England, while English troops used a White Cross in 1188. Philip II, Henry II and Count Phillip of Flanders met at Gisors in northeast France on January 13th 1188, to choose the three colours of crosses to be worn by their respective soldiers. The colour of three crosses signified which language to communicate with the troops.[25] George of Capadocia (modern day Turkey) or St. George, the Patron Saint of England, is venerated as a legendary champion of Truth and defender of the Christian religion.

With this chiefly ascent, Busby successfully riffed off Crusades history, by embedding the red version of St George’s Cross used by the French in the Kings’ Crusade, or the Third Crusade. Doubtless, these machinations entertained Busby greatly, particularly as this red cross was subsequently adopted by the English. Busby was, therefore, mocking the French. Simultaneously, Busby was signaling that fears were stoked in Māori about France as a perennial potential enemy, which was a tried and true means for manipulating people into alliances to serve rulers more interested in state formation. In his role as ‘British Resident’, New Zealand’s first official was luring Māori chiefs to ascent to the jurisdiction of British Maritime Law, which meant Busby was formalizing the assertion of a Discovery Doctrine element known as Tribal Limited Sovereign and Commercial Rights.

The Doctrine of Discovery was a secret piece of international law that emerged during the Crusades, which targeted the ‘Holy Lands’ between 1096 and 1271, when the Vatican Empire asserted a worldwide papal jurisdiction to justify Holy Wars fought by the Knights Hospitallers, the Knights Templars, and the Teutonic Knights.

Muslim Saracens were cast as ‘Infidels’ and Christians could ‘legally’ reconquer their lands by divine mandate, which limited the property rights and self-government of non-Christian peoples, to serve the diabolical ambition to forge a universal Christian empire.[26]

The Discovery Doctrine was further developed between European nations in the 15th Century, from whence they were forging maritime empires, and was designed to mitigate the chances of competing nations making expensive war with their technologically-even European competitors at the cost of much ‘blood and treasure’. The European Maritime Powers thought it would be easier to gain territory off ‘New World’ aboriginal and indigenous peoples, whom were cast as ‘savages’.

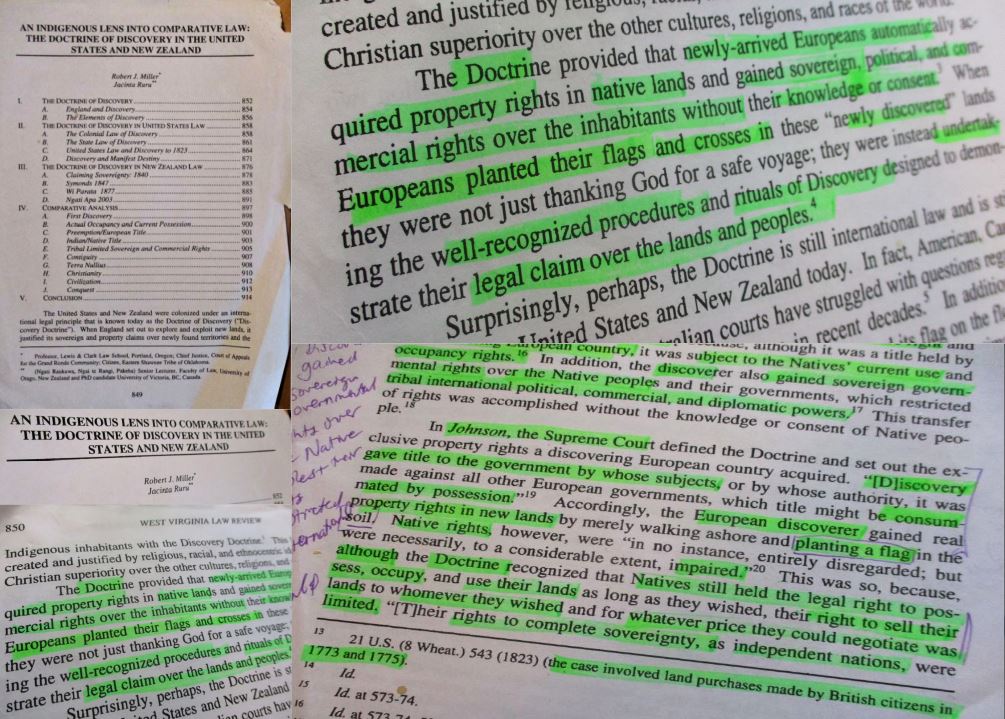

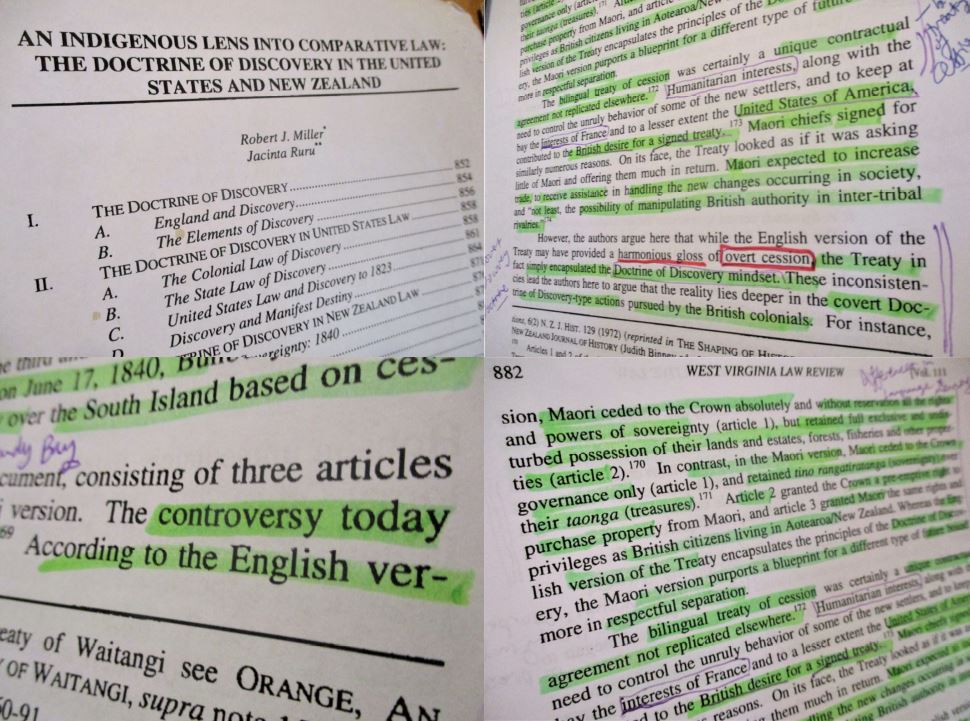

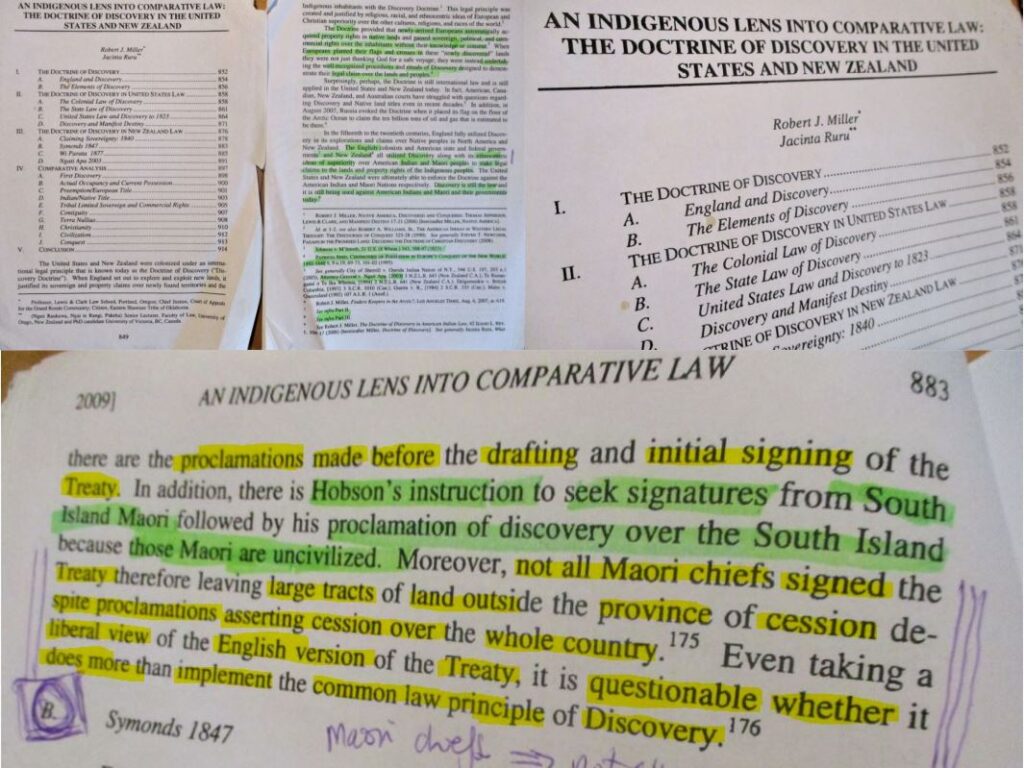

Historian and legal scholar Steve Newcomb stated that a doctrine in international law known as terra nullius, derived from Roman law, legalized territorial expansion of ‘uninhabited’ lands by holding that enemies had no rights to land and property as the documentary, The Leech and the Earthworm shows. Newcomb, a Shawnee and Lenapa Native Canadian, argued that the Catholic Church altered this doctrine to terra nullus — meaning people living in the New World were deemed too ‘primitive’ to be considered ‘sovereign’ because they lacked Christian mythology and therefore had no legitimate legal or political status. Newcomb’s position is corroborated by Robert Miller, Jacinta Ruru, Larissa Behrendt and Tracey Lindberg in their 2010 book, Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies.

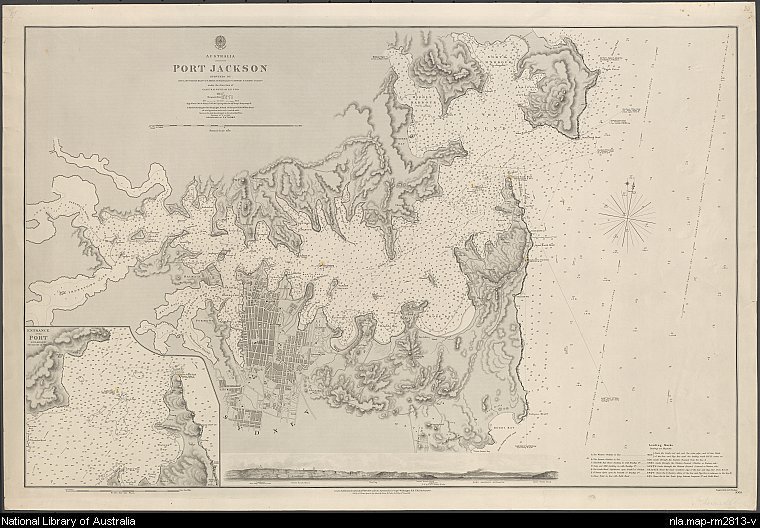

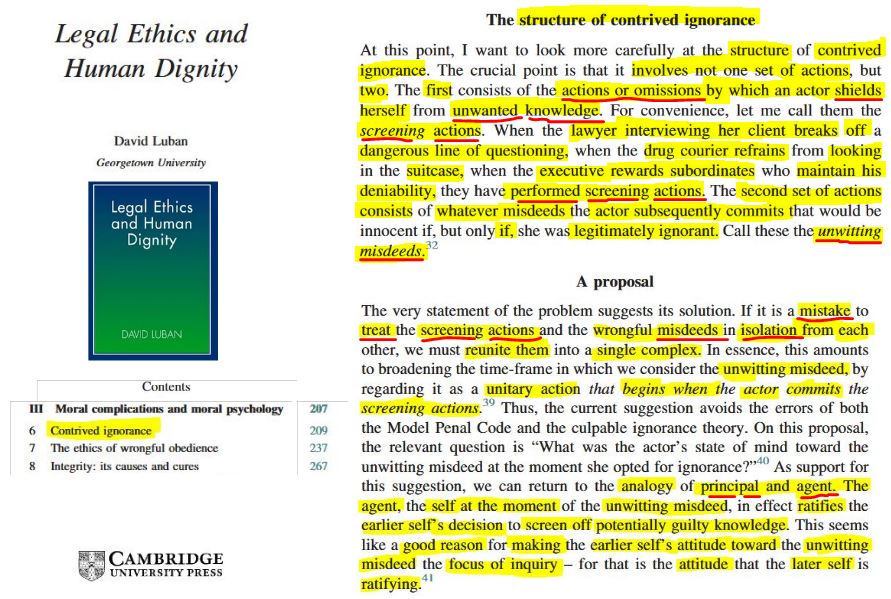

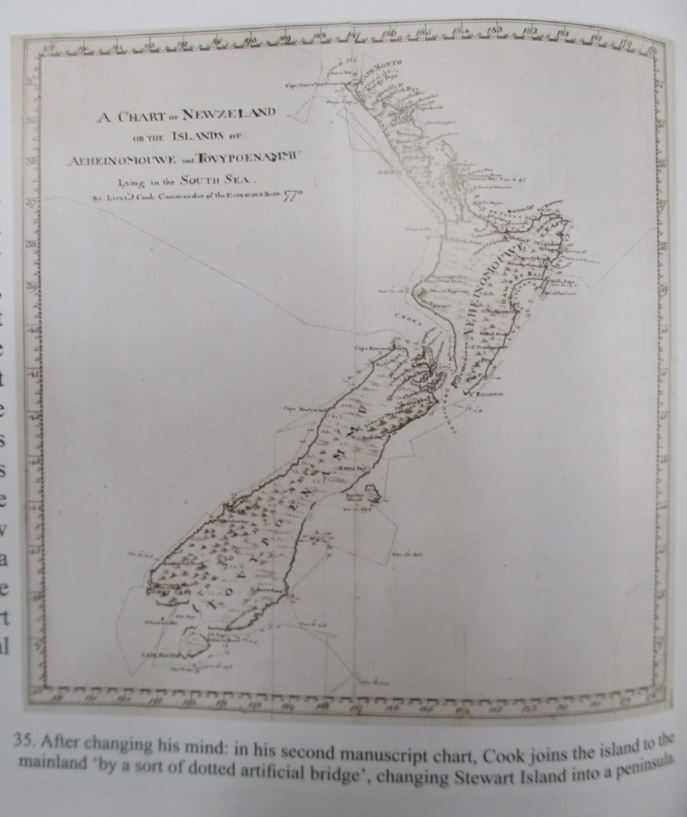

In her book, Tears of Rangi: Experiments Across Worlds, Anne Salmond located Captain Cook’s surveys and charts of the ship’s course around coastlines that were traced onto gridded paper to fix latitude and longitude in the Discovery Doctrine. With brilliant prose that captured the essence of the collisions of ‘two worlds’ that had already occurred and would happen again, Salmond wrote:

“In the alchemy of hydrography, the land was reduced to coastline, stripped of most of its features and emptied of people — a terra nullius. With its inhabitants erased, the sea was similarly abstracted into a blank, two-dimensional watery wasteland — a mare nullius, waiting to be discovered and claimed by European powers.”

Although Salmond did not explore the unfolding events that led to a compact between the British Crown and Māori in 1840, and its impacts, as elements of the Discovery Doctrine, the ethnographic historian did capture the uneven playing field of a world power applying its will over aboriginal and indigenous peoples.

On the American continent, the English colonizers went further and got around the law of terra nullus by invoking another doctrine, vacuum domicilium. This doctrine claimed that because the ‘savages’ ranged rather inhabited the ‘unmanned’ wild country and had failed to cultivate and farm land with livestock as ‘God’ had evidently intended, landgrabs were justified, as the account of “That Unmanned Countrey” — cited in Samuel M. Wilson 1999 book, The Emperor’s Giraffe: And other Stories of Cultures in Contact — explained.

As indigenous law scholars Robert J. Miller and Jacinta Ruru stated in the West Virginia Law Review:

“When Europeans planted their flags and crosses in these ‘newly discovered’ lands they were not just thanking God for a safe voyage; they were instead undertaking the well-recognized procedures and rituals of Discovery designed to demonstrate their legal claim over the lands and peoples.”[27].

Indeed, after conning Māori chiefs to ascent to a flag that incorporated the Crusader’s Cross of St George, Busby wrote to New South Wales Governor Burke:

“As this may be considered the first National Act of the New Zealand Chiefs it derives additional interest from that circumstance. I found it, as I had anticipated, a very happy occasion for treating with them, in a collective capacity, and I trust it will prove the first step towards the formation of a permanent confederation of the Chiefs, which may prove the basis of civilized Institutions in this Country.”[28]

The British Resident’s official correspondence was sanitized and at odds with his private words and his ‘public’ deeds. By civilized institutions, he really meant public and private sector organizations controlled by British Settlers, and by British élites doing stints to control the colony’s development and, either returning home with newly forged fortunes, or establishing large estates to rival those of the aristocracy.

Next, Busby antagonized a local chief, Rete, by bossing him and his hapū around about how to conduct their logging commerce. Rete was also annoyed that Busby had taken control of large tracts of land. Brazenly, Busby lobbied for Rete’s execution after the evidently ‘insubordinate’ chief ransacked Busby’s storehouse,[29] and the British Resident copped a wood-splinter wound to his face when a musket shot hit the back-door frame, from where Busby had disturbed the intruders one night.

Chief Rete and his accomplices were in the midst of exacting a muru, or ritual compensation, for Busby’s ill-received foray into authoritarian rule.[30] By inflicting the muru, Chief Rete was carrying out Māori customary law for Busby’s transgression. Reverend Henry Williams advocated land forfeiture and banishment from the district.

Sir Richard Bourke permitted James Busby to inflict a retaliatory punishment against Chief Rete, thereby setting in train New Zealand’s first official land confiscation, eviction and village razing by fire in 1834.

Instead of execution, New South Wales Governor Sir Richard Bourke permitted, with the authority of the Executive Council in Sydney on 27 January 1835, inflicting another humiliating retaliatory punishment. After calling a hui with 20 chiefs on 14 March, Busby gained the cooperation of 12 chiefs to attend the confiscation after he bribed them with blankets. Busby timed this hui occur while a ship of war, the HMS Hyacinth, was in the Bay of Islands, just the HMS Alligator was present when Busby convened a prior hui to commit the chiefs to punish Rete, in late October 1834. On both occasions, Busby had asked the ships remain while he convened his meetings with the chiefs.

Rete’s huts were burnt, he was banished and 200 to 300 acres of his village, Puketona, were confiscated, which Busby renamed Ingarani, the Māori transliteration for England.[31] Busby later burnt down traditional fishing huts on land at Waitangi he had ‘purchased’ when he found out that Rete and his friends had been using them. Busby had ‘allowed’ continued use of the huts by Māori, but set fire to them without notice and this action further strained relations.

The incontrovertible fact is that Busby acted as an agent provocateur seeking to antagonize Chief Rete and other chiefs, having gained chiefly recognition of British Maritime Law. Busby’s provocation occurred after he had conned chiefs to ‘vote’ for a flag of national shipping and therefore, volunteer their submission to British Maritime Law, and join in the system of international law.

The calculus of Busby’s machinations was to provoke the chiefs through his land-swindling, interfering and symbolic assertions of authority in order to train the rangatira into submissive acts. These machinations would sooner or later justify holding a de facto court, which would add to the British Government’s ability to justify annexation by settlement.

Thus, the first British Official, who gained his Resident Magistrate post through bribery, inflicted New Zealand’s first official land confiscation, first official scorched earth village razing and first official evictions — while supposedly under British ‘protection’.

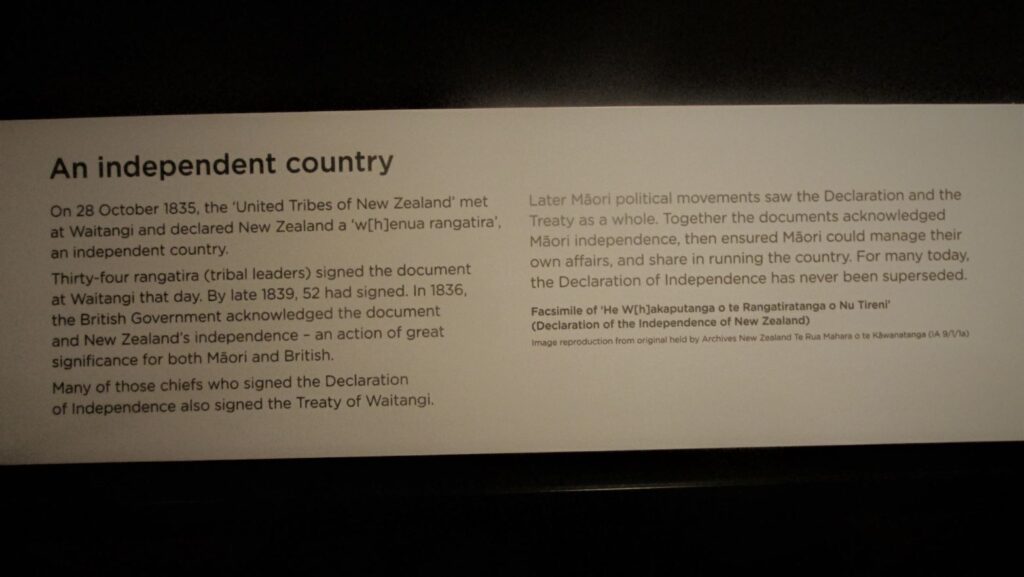

Having successfully inflicted the first land confiscation with the participation of a dozen rangatira, three quarters of whom were bribed with presents, Busby then deployed his defining confidence trick: gaining chiefly participation in signing the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’, or He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene.

Busby stoked fears that Māori would be enslaved on the basis of a letter sent to him by a delusional Frenchman, Charles de Thierry, who claimed to declare sovereignty. Busby’s modus operandi was to turn any threat, real or perceived, into an opportunity and was part of the British strategy to game Māori.

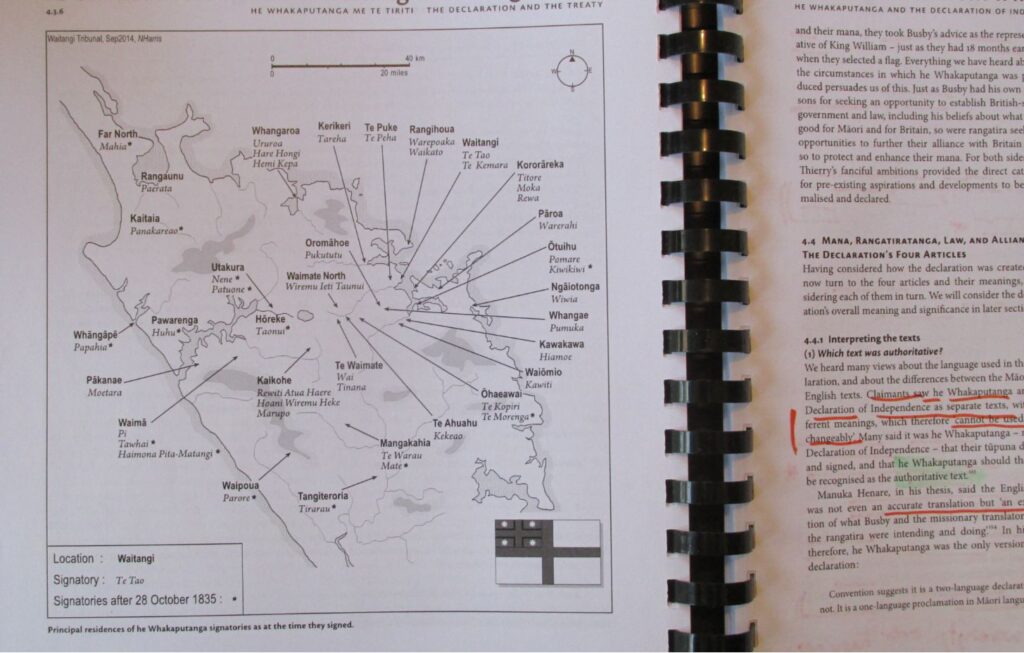

Indeed, the origin of this ‘Declaration of Independence’ can be traced back to the ‘Letter to King William IV of October 5 1831’, which had been triggered amid widespread rumours of a French ship coming to take lands. Following the first signings of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ — 33 in all on October 28th — Busby eventually gained a full deck of cards worth of 52 chiefly marks and signatures over a four-year period, including chief Te Wherowhero.[32]

In regard to whether the 1835 Declaration was Busby’s initiative, or that of Ngāpuhi rangatira, Ngāpuhi kaumātua Erima Henare challenged the credit that Pākehā historians have bestowed on Busby. In the Ngāpuhi Speaks report, it was conveyed that Erima Henare pointed out that proof of Ngāpuhi agency in He Whakaputanga is the fact that when the iwi gathered at Busby’s residence at Waitangi in 1835, they fed themselves, while five years later, the missionaries stumped up for the food.

Granted, there was clearly far more rangatira agency in the discussion that resulted in the composition of the final texts for the 1835 Declaration, than with the both versions of the Treaty, which were composed entirely by Pākehā.

However, it is ultimately a fallacy of evidence to suggest that who laid on the kai for the home crew is proof of who had control of the foreign ship’s rudder carrying the dispatches, with the ‘all-important’ English versions of any letters, declarations or treaties carrying the marks of rangatira, as well as the Māori language versions. Particularly, as Busby had deliberately under-catered for the festivities following the vote for the Te Kara flag and the creation of a shipping register on March 20th 1834.

Busby did not want to ever have to cater for Māori because he saw himself as above ‘the Natives’ and he was intent on establishing imperial customary rights with himself as Crown Agent.

That occasion of under-catering in 1834 — which followed the staged theater in a tent constructed of shipping sails, wherein chiefs were coaxed to prostrate themselves in order to pass under a British shipping rope — led directly to the chiefs bringing their own catering for the signing of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’. And because Busby was, in effect, conjuring more tracks and sleepers that would eventually culminate in an improvised fast-speed Waitangi Treaty track section, where Māori would not see the events moving around them on the slower Colonial Law Track.

Indeed, Prophet Penetana Papahurihia correctly sensed after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi that the travelling Waitangi Treaty Theater Production Company had caught Māori in a ‘whirl-pool’ — as the quotation cited at the start of this illustrated essay succinctly captured.

The significance of Busby’s machinations can be brought into sharper focus when it is recalled that the British Resident and his servant, William Moore, were shot at when they disturbed Chief Rete sacking his storehouse. In nearly all accounts of this incident, the reason why Rete was stealing Busby’s stores is omitted, thereby rendering the Ngāti Tautahi chief as a common thief. The Waitangi Tribunal omitted Chief Rete’s reason, missed the reason altogether, and essentially uphold Busby’s framing of the event as a plunder and attempted murder. Even Ngāpuhi Speaks misses the full significance, despite this report recounting that Chief Rete was inflicting a muru, since Busby was land speculating and threatening to stop the logging trade — as Pairama Tahere recounted.[33]

Ironically, after the first 1840 Waitangi Treaty signings, Chief Hōne Heke was no longer able to charge anchorage fees because authority had shifted to the Crown’s officials and Hobson moved the capital from Kororāreka to Auckland, which caused significant economic decline. Heke’s rangatiratanga, or chieftainship, was being interfered with and decisions were being made without Māori. Chief Heke had failed to care that Chief Reke had sensed his rangatiratanga was being breached by Busby and failed to see that Busby’s actions were about laying a two-trunk line comprising of a Treaty Track and a Colonial Law Track.

The Ngāpuhi Speaks writers miss the point about why exactly Busby’s first reaction on learning the identity of the culprit, was to insist for Rete to be executed. And, Ngāpuhi Speaks, along with O’Malley in Beyond the Imperial Frontier, also omitted that the informant to Henry Williams was Ngāpuhi chief Hōne Heke Pōkai, of the same village, Puketona, following his relative and wife of Rete unbraiding the chief in a quarrel. Rete’s wife had discovered a rug of distinctive make that Reti possessed, as R.A.A. Sherrin’s account, “The Growth of British Authority” in Early History of New Zealand revealed in 1890. According to Sherrin, Reti had beaten his wife and she disentangled the argument by uncovering the origin of the rug.

Yet, the Shakespearean irony of Rete’s wife unbraiding her husband with the discovery of a woven threaded-mat of European make — that had been taken from William Moore’s room — was lost on Sherrin, whose account was filtered by a Colonial-era mindset. The friction of new imperial machinations rubbing up against aboriginal and indigenous culture already frayed by the altered power relations underpinning the sexes, hapū kinship, and trade as family groups were compelled to relocate villages to be near swamps to harvest flax as a consequence of the arrival of muskets. It would appear Rete inflicted a muru upon Moore for sneaking into the storehouse to retrieve Busby’s ammunition belt.

Hōne Heke failed to unbraid the complexity of the event, and likely let the emotional roil of Rete beating his relative become entangled with the pressure that Busby, and other colonists, had asserted to find the culprit.

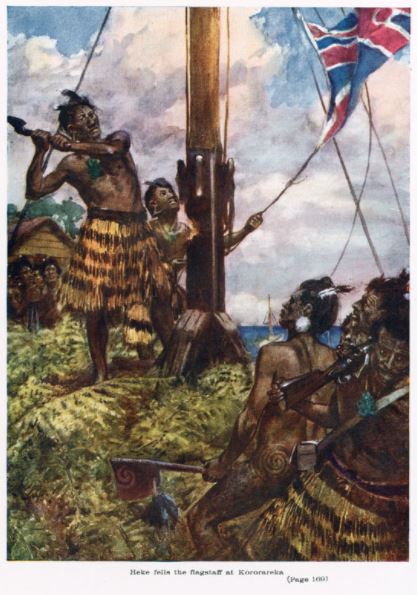

Thus, the first recorded ‘domestic’ that was entangled with the machinations of New Zealand’s first British official, escalated into an entire village being razed, as well as land of an entire hapū being confiscated and its people becoming the first homeless ‘natives’ by a decision of the Executive Council in Sydney, whom officially it would appear, knew nothing of the British Resident’s culpability. Therefore, Chief Hōne Heke would later surely have rued the day, October 27th 1834, that he had ever performed the role of a ‘tell-tale-tit’, since he later, rather famously, was driven to cut down the flag-staff on Maiki Hill above Kororāreka (Russell), four times, in 1844 and 1845 to challenge the British take-over.

Because the muru that Rete was trying to inflict on Busby was construed as an act of theft, the result is that the Busby-Rete Events Cluster has often been overlooked. Therefore, the full extent of the irony embedded in Heke’s flag-pole chopping has also been lost on earnest historians, Treaty scholars and Treaty workshop teachers. Particularly since Heke’s tell-tale-tit activities led directly to Busby burning the fishing huts at Waitangi where the homeless Rete had taken refuge. Thus, Busby’s machinations are also the story of Britain’s first official inflicting vindictive systemic homelessness in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In other words, New Zealand’s first British official wanted the life of the one man who was an immediate threat to his power, however limited, to be snuffed out in 1834. Because, if the truth got out in official or published accounts that Busby’s bossiness over Rete’s business — as well as his sly land acquisitions from chiefs unfamiliar with European conceptions of private land tenure — then the Discovery Doctrine logic of Busby’s mindset would have been laid bare.

These are the reasons why Rete’s ransacking action of Busby’s storehouse were rendered as a ‘theft’, and why — like so many crucial details in history — Busby’s interference into Rete’s log-trade was only carried in oral accounts by the ‘little people’ whom historians have a tendency to overlook. Even Anne Salmond misses this detail that Rete was inflicting a muru not simply over Busby’s unscrupulous land acquisitions such as the property at Waitangi, in her epic, Tears of Rangi, despite her reading Ngāpuhi Speaks.

In his letters, Busby’s real attitude toward Māori rangatira is revealing. In a 16 June 1837 dispatch sent by Busby, the British Resident proposed the British Crown make a treaty with Māori and sought to persuade British to establish a protectorate government in New Zealand.[34] Busby referred to the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ to explain his logic:

“that the congress of chiefs … is competent to become a party to a treaty with a foreign power, and to avail itself of foreign assistance in reducing the country under its authority to order; and this principle once being admitted, all difficulty appears to me to vanish.”[35]

Moreover, Busby claimed that a treaty would be regarded by the chiefs as an acquisition of power rather than a surrender of power because:

“the New Zealand chief has neither rank or authority but what every person above the condition of a slave, and indeed the most of them, may despise or resist with impunity. It would, in this respect, be to the chiefs rather an acquisition than a surrender of power.”[36]

Busby construed Māori civilization as disorderly.

This trick of psychological projection — which is common habit of highly functional psychopaths, psycophantic sociopaths and clichéd narcissists employed by empires — meant Busby conveniently did not acknowledge the sleight of hand of European agency underpinning the disruption of Māori civilization. In particular, the British agency behind structurally baiting Māori, such as Hongi Hika and his nephew, Waikato, to lure them toward the path of internecine warfare.

Such structural baiting would predictably and eventually bring some of the aboriginal and indigenous peoples to the table to negotiate an alliance to stabilize matters, especially amid heightened fears of an external enemy.

Therefore, the structural racketeering that underpinned state formation over the islands of New Zealand is one of the forces that had stirred the whirlpool that Prophet Papahurihia had sensed would take beyond 200 years to be widely known and corrected after its decipherment.

The Māori language version known as He Whakaputanga o 1835 bestowed authenticity to the English language version since this version was derived from the te reo Māori version, which was primarily drafted by Henry Williams, and polished by Eruera Pare Hongi.

To the British Crown, the English language version of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ formalized New Zealand as an independent state controlled by a confederacy of chiefs. It was recognized as such by the British Crown in 1836 and the British Parliament in 1838, but more accurately applied to the Northern parts of the North Island, as well as the Waikato and Hawke’s Bay. The British were able to construe that New Zealand was an ‘independent state’ — while, curiously, at the same time the entire islands of New Zealand became a protectorate of the British Crown.

While family groups and tribes exercised independence, their capacity to defend themselves against the full force of a foreign power, whether French, English or American, over several years was questionable. To the rangatira that signed He Whakaputanga o 1835 (or ‘A Declaration of New Zealand’s Māori Sovereignty’), the paramount sovereign power and authority that they asserted was derived from the sustaining and nurturing of whenua, or land. Because the United Tribes sought an alliance with the King William IV in return for protection from foreign invaders, as well as trade opportunities, New Zealand, in effect, became a protectorate of Great Britain.

The 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ (He Whakaputanga o 1835)

Snapshot: The 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ was designed to lure Māori chiefs into a British Protectorate jurisdiction, and to forestall French missionary influence, as part of a long-game to perfect the incomplete title claimed by Freemason Bro. Captain James Cook, by stealthily gaining full paper sovereignty by a hidden track.

The key points and differences between the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835 version and the English language ‘Declaration of Independence’ of 1835 version, are as follows.

In Article One of He Whakaputanga o 1835, the chiefs claimed paramount sovereign power and authority, which was derived from the sustaining and nurturing of wenua, or land. This assertion to absolute authority meant that the rangatira exercised customary law and their responsibilities anchored in the well-being and mana in their hapū regions. The Te Wakaminenga gatherings maintained by the Northern Alliance chiefs are referenced in Article One of the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835. As I mentioned previously, the institution of these Te Wakaminenga gatherings dated back to 1808, following the Ngāti Whātua victory over Ngāpuhi in the Northland battle of Moremonui at Maunganui Bluff, in 1807, at the beginning of the Musket Wars (1806-1845).

Crucially, they did not usurp or over-ride hapū autonomy, and if there was consensus reached, the agreements were not binding. While in Article One of the English language version of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’, the rangatira asserted a confederacy of Tribes that constituted an ‘independent state’.

The Second Article of the 1835 He Whakaputanga states this hierarchy of authority, expressed as kingitanga, mana and Tino Rangatira are derived from the land and hapū, or extended whanau units. Therefore, the authority of the paramount chiefs is grounded in wenua, or land, and whakapapa, or genealogy. The chiefs declared that they were responsible for framing laws and only persons appointed by them would be authorized to set down laws consistent with the Confederation of New Zealand’s meetings, such that a governor could not make laws in conflict with the rangatira laws.

In the English language version, Article Two rendered “all sovereign power and authority” to its hierarchical effects of mana to exert control, whereas in the Māori language version, mana’s source is derived from the land. Therefore, in the English language version, there was a perceptible sleight of hand to incrementally shift power upward and away from the source of chiefly power — the land and genealogy — to construct a hierarchical model for later de-construction by pen-quill and parchment paper.

In Article Three, the paramount chiefs resolve to meet each year in the autumn at harvest time, under the auspices of Te Wakaminenga gatherings. The intent of these annual Runanga was to dispense justice, ensure peace and confront wrongdoing and lawlessness and facilitate fair trade in commerce. Article Three also called upon iwi and hapū in other areas to join Te Wakaminenga and quit inter-tribal warfare, which reinforced the northern rangatira of Ngāpuhi declaring that the ‘land [was] in a state of peace’.

Article Four of He Whakaputanga emphasized an extension of friendship and alliance with the British monarch and Britain, which had its roots with chiefs Hongi and Waikato visiting England and King George IV on November 13th 1820. The rangatira expressed appreciation for the King’s recognition of their shipping flag and then promised to extend friendship and care toward British settlers and traders. The Tribal Confederacy entreated to the King of England to be the Protector from all attempts upon their mana and sovereignty. Rather crucially, in the English version, mana and sovereignty was rendered as independence. In seeking the King to act as ‘matua’, rangatira were actually asking the King to be a parent to his own British ‘family’!

Meanwhile, in the English version, this parent or protector role was rendered to frame the independent state as a candidate for protectorate status of the British Empire.

In his 2009 review for the Waitangi Tribunal, Samuel D. Carpenter correctly critiqued that the English language version rendered the chiefs’ intention for friendship and alliance into a meaning that fitted the imperial paradigm, or mindset. Carpenter wrote that such “protectorate language was a prominent code for British control at the time.”[37]

In the drafting of this 1835 Declaration, the crucial differences in stating chiefly sovereignty belies Busby’s machinations to construct the edifice of national autonomy for later de-construction. In the English language version, chiefly sovereignty is construed as a confederacy comprising a small number of chiefs whom essentially are placed — unwittingly — in a position to over-reach their authority to claim an independent state, with a binding hierarchical power structure that sought protectorate status within the orbit of the British Empire. Whereas, in the Māori language version, He Whakaputanga o 1835, hapū autonomy remained intact since chiefly authority was anchored in the well-being and mana in their hapū regions that signed.

The crucial differences between the drafts of the Māori language and English language versions of the 1840 Waitangi Treaty is not simply because Busby recruited the help of Eruera Pare Hongi, to draft the Māori language version of 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’. The real reason is because the British game had been to erect the edifice of an independent sovereign state for its deconstruction at a later date either by legislation, or treaty.

To the British Crown, the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ formalized New Zealand as an independent state supposedly controlled by a confederacy of chiefs precisely because its Māori language version known as He Whakaputanga o 1835 – could be construed as the authentic origin of the English language version. It was recognized as such by the British Crown in 1836 and the British Parliament in 1838, but more accurately applied to the Northern parts of the North Island, as well as the Waikato and Hawke’s Bay.

To the rangatira that signed He Whakaputanga o 1835 (or ‘A Declaration of New Zealand’s Māori Sovereignty’), the paramount sovereign power and authority that they asserted was derived from the sustaining and nurturing whenua, or land. Because the United Tribes sought an alliance with the King William IV in return for protection from foreign invaders as well as trade, New Zealand, in effect, became a protectorate of Great Britain.

Crucially, the one account that survives is Busby’s report — which is rather telling since some ‘unhelpful’ independent accounts of the Te Kara national flag of shipping event of 1834 had been produced, that contradicted Busby’s propaganda. This is despite Reverend Henry Williams, a prolific diarist, and CMS printer James Clendon, being present.[38]

This sparseness in accounts was to be repeated when the Treaty Theatre Track advanced to its historic production at Waitangi in 1840, with Captain William Hobson as the Waitangi Theater Company director.

And, as we shall see, the genealogy of language text versions was switched when the compressed time came to compose the 1840 Waitangi Treaty parchments.

Key Finding: Britain’s first official, James Busby, incrementally drew rangatira into British jurisdiction. First, by conning chiefs in 1834 to select a flag of national shipping that displayed England’s orientalist St George’s Cross, to save them from the maw of British Maritime Law. Second, by getting them to inflict New Zealand’s first British-endorsed village razing to establish a confiscated parcel of land named England. And then, Busby conned rangatira to sign the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand’, to create the edifice of an ‘independent state’, for its later deconstruction.

The 1840 Waitangi Treaty (or Te Tiriti o Waitangi o 1840)

Snapshot: The Treaty Theatre pivoted upon a fulcrum of deceptive translation differences in the 1840 Waitangi Treaty texts that hid the deceptive power crime to win native signatures and paper sovereignty by weaponizing the physical dimension of time.

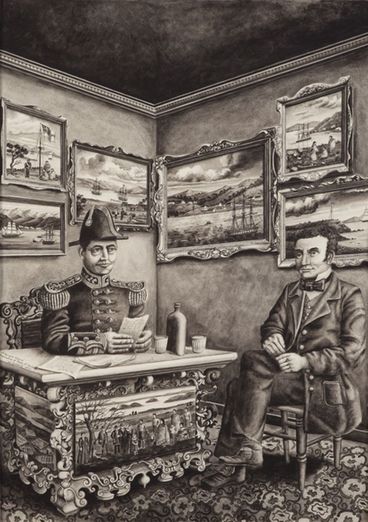

Like James Busby, Royal Navy Captain William Hobson was volte-faced in his dealings with Māori. Behind the friendly mask, was a scheming face and an ambitious egotistical mind.

Captain Hobson, who was a mid-ship man in the Napoleonic Wars, first came to New Zealand in 1837, when he commanded the fittingly-named frigate, HMS Rattlesnake, to answer Busby’s dispatch to Sydney for help to quell fighting between two warring chiefs Pomare II and Titore. While briefly in New Zealand between May and July, he visited other parts of the North Island during which time he gleaned information to serve the British Masonic Empire.

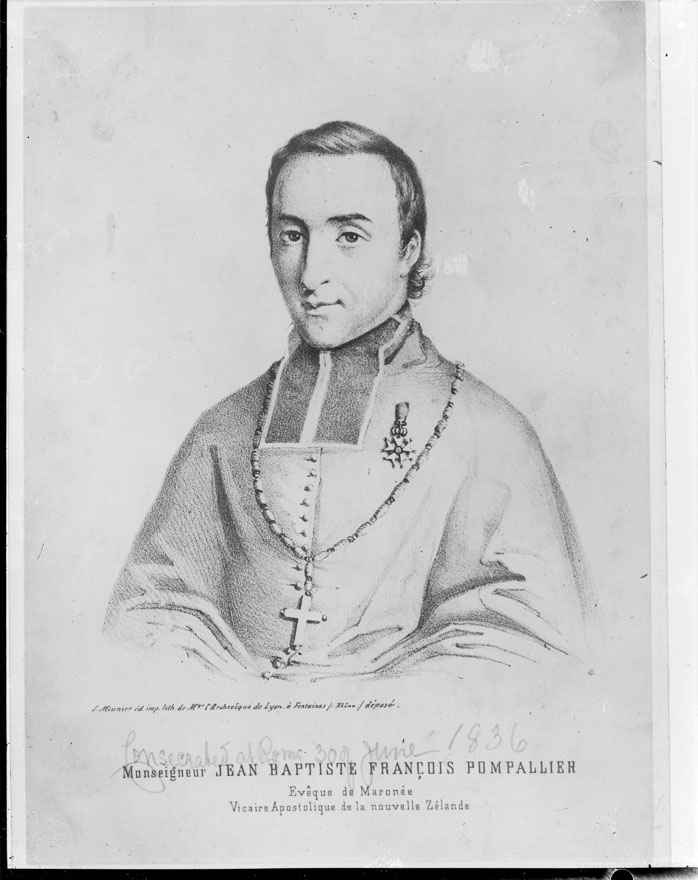

The Royal Naval Captain had envisaged a ‘factories scheme’ for New Zealand that described a system of naval-protected trading posts owned by the British Crown, following a treaty. Captain Hobson’s 1837 plan envisaged the factory enclaves would be controlled by a British Governor, whom would have authority over Pākehā and Māori. In effect, this scheme meant the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Normanby, and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Bro. Palmerston, well-knew that Captain Hobson’s Factory Scheme was based upon the factory trading system used by the British East India Company.

That factory trading system had been copied from the Portuguese to gain a foothold in India in 1668, first on the Island of Bombay, its port and its harbour. Governor Bourke wrote to the Colonial Office conveying that Hobson’s proposal was premised on ‘Māori’ conceding to the factory plan on terms of mutual interest. Thus, the factory plan relied on the compact of treaty. However, Hobson was evidently less confident than Busby that a treaty would work, because he felt Maori had no form of government and any hui with chiefs claiming to be the heads of the United Tribes would likely result in bloodshed, as Matthew S.R. Palmer pointed out in his 2008 book, The Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand’s Law and Constitution.[39]

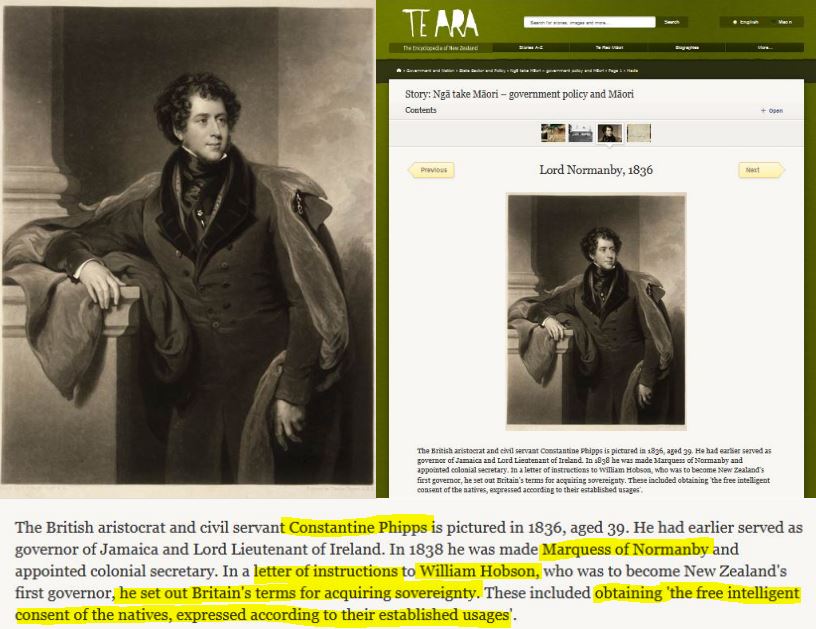

Thus, when Lords Normanby and Bro. Palmerston tasked Hobson in 1839 to treat with the ‘Native Chiefs’ for their willing and conscious cession of sovereignty and informed consent to grant monopoly rights to extinguish native land estates, they were sending in 1839 no ordinary Royal Naval Captain. They also knew the value of gaining control over the entire islands of New Zealand. To wit, Lord Normanby’s written instructions handed to Captain Hobson on the 14th of August 1839 in England, opened by stating:

❝We have not been insensible to the importance of New Zealand to the interests of Great Britain in Australia, nor unaware of the great natural resources by which that country is distinguished, or that its geographical position must, in seasons, either of peace or war, enable it in the hands of civilised men to exercise a paramount influence in that quarter of the globe. There is probably no part of the Earth in which colonisation could be effected with greater or surer prospect of national advantage.❞

To achieve this strategic end – which essentially restated the occult Masonic vision of Captain Bro. Cook – Lord Bro. Palmerston and Lord Normanby made the conscious decisions to sign-off on the trickery of appearing to gain an agreement to establish a governor to rule over white settlers, while slyly gaining paper sovereignty to rule over ‘Māori’ and Pākehā alike. In the British quest to achieve the appearance of sovereignty gained by treaty cession, Hobson had been instructed by Lord Normanby to rely on the protestant missionaries as “powerful auxiliaries” to persuade ‘the Natives’.

Normanby’s propagandist instructions implicitly ordered Hobson to lie by omission, talk up the benefits and emotionally hijack the rangatira with the novelty of contact, including presents of tobacco and blankets. The details of how exactly they would pull off the epic swindle would be left to that part of the Treaty Cliqué that were in, or would travel to, the South Pacific. The trickery was designed to eventually lead to structural entrapment – to justify a war of sovereignty by construing any Māori who fought back as being in rebellion, since British Freemasons and Protestant settlers would maintain supremacy over the public and private systems of propaganda in Britain and New Zealand.

That structural entrapment would take the form of provoking Māori into reacting to incursions on their sovereignty, lands and customs, and would be the catalyst for the Northern War of 1845-46[40] and the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872.[41]

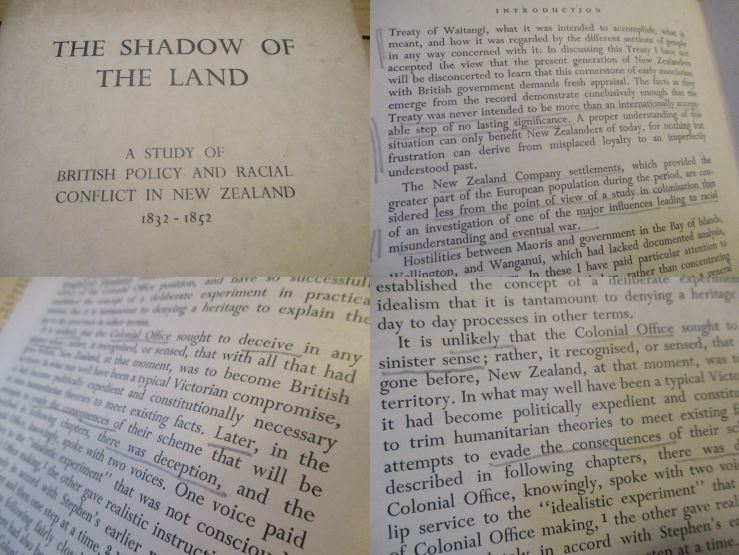

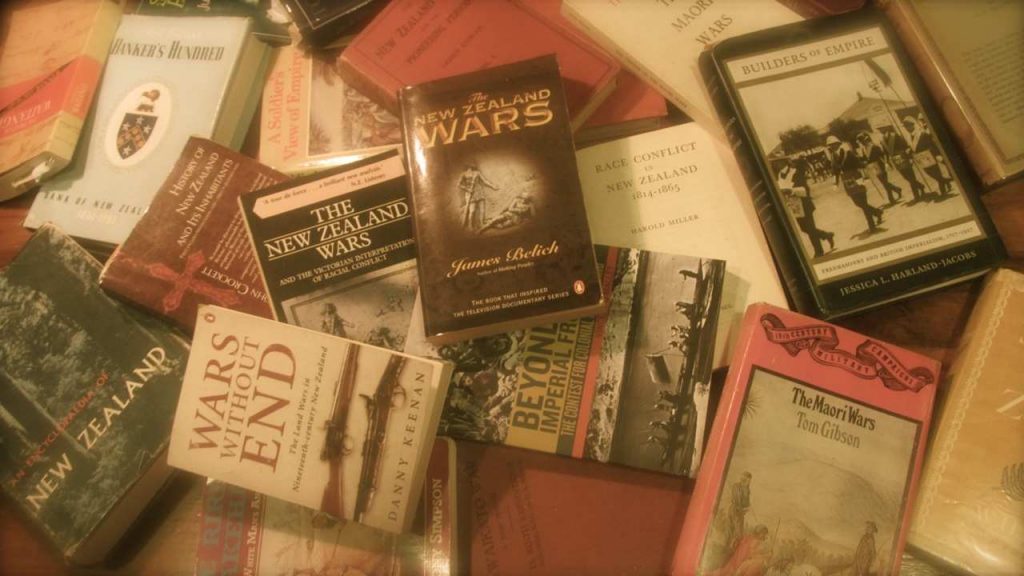

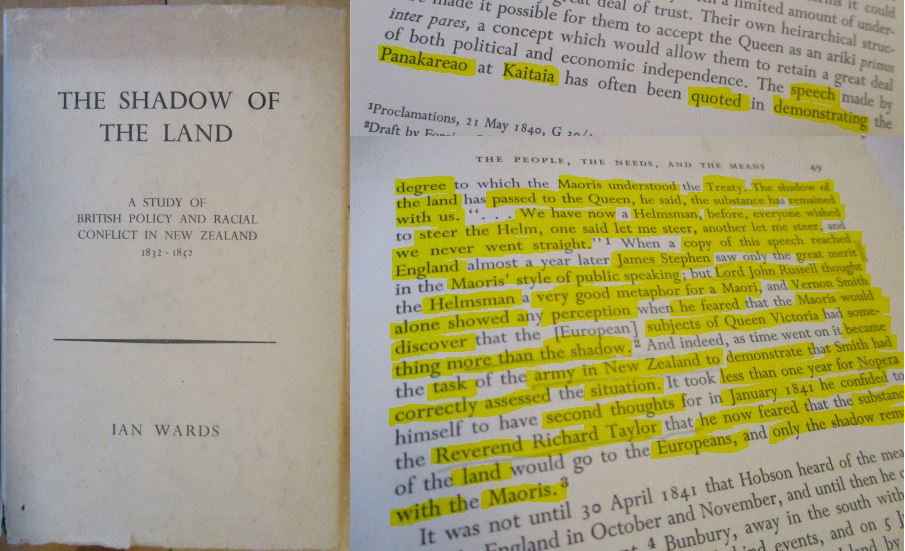

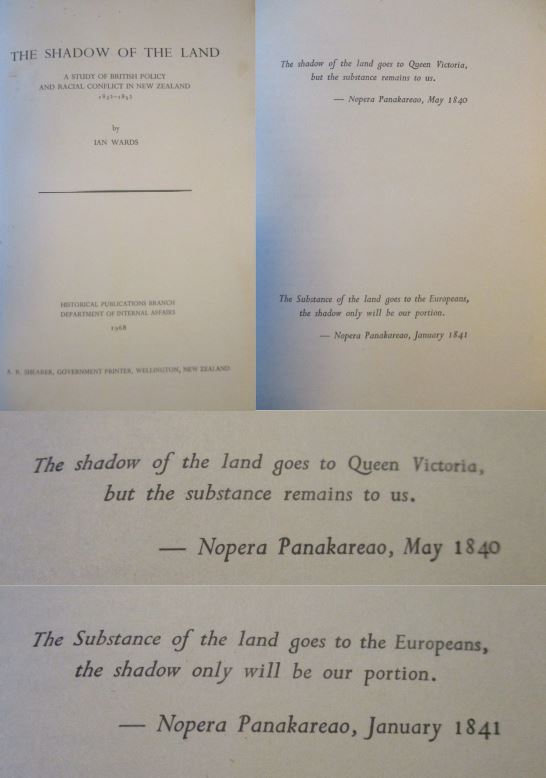

Much important research has been conducted since the emergence of the Māori sovereignty and land rights movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Before those works emerged, however, the New Zealand Government’s Department of Internal Affairs changed course on a historical project that historian Ian Wards was working upon. He was planning to show the interplay of military, political, and social affairs with their impacts on racial conflict and military development in New Zealand’s history, but the project was claimed to be too ambitious in 1966. Subsequently, a decision was made to scuttle the army research. Fascinatingly, these decisions and indecisions meant there was no major historical works published on the Northern War of 1845-1846 and what was really the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872, between James Cowan’s two volumes, The New Zealand Wars, of 1922 and 1923, and James Belich’s, The New Zealand Wars, of 1986.

The result of Ian Wards’ truncated research was the Department of Internal Affairs’ 1968 book, The Shadow of the Land: A Study of British Policy and Racial Conflict in New New Zealand 1832-1852. The decision to change course appears to have been to manage the revision of history at a time increasing numbers of Māori were beginning to find their feet walking the grounds of New Zealand’s universities. To this face-saving end, Government historian Ian Wards wrote that on February 5th 1840, about 500 northern chiefs gathered at Busby’s property, Waitangi, where:

“it was explained in return for their cession of sovereignty and their guarantee that the Crown would have the sole right of pre-emption over such lands as they wished to sell, they would have full rights of British citizenship and the uninterrupted enjoyment of their lands and other natural resources which had previously contributed to their livelihood”.