By Steve ‘Snoopman’ Edwards

Re-Discovering the Big-Picture of Empire in Aotearoa

One hundred and forty-five years after the wars between native Māori and British imperial and colonial forces ended, most New Zealanders remain oblivious to the conflicts’ Masonic underpinnings. For those not disposed to empathize with Māori, this obliviousness works as a vector that transmits racism throughout the British-American tax haven jurisdiction of New Zealand. Furthermore, this racial prejudice persists structurally throughout the realm of New Zealand’s major and significant economic, political and cultural institutions.

This colour-based prejudice against the native people of New Zealand hides a largely ignored problem of class-stratification, or a hierarchy of privilege based on economic wealth accumulation, control of key institutions and the valourization of status addiction. It is no small irony that when the framing of discussions on racial prejudice does widen to include the phenomenon of a hierarchically class-structured society, such discourses frequently fail to nail the root cause of systemic material inequality or structural dispossession: Oligarchism.

During the period of New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872, the secret society of Freemasonry was, essentially, an expression of oligarchism, which is the belief in the right of super-rich people to rule over humanity through the structural domination of resources, including institutions, covert networks and the exploitation of secret mechanisms.

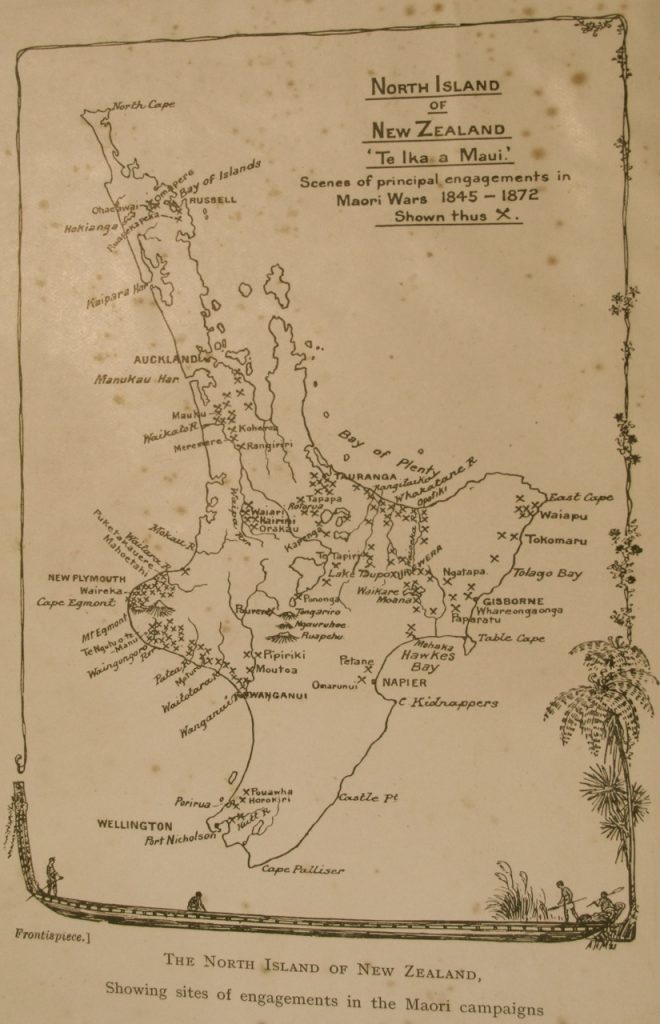

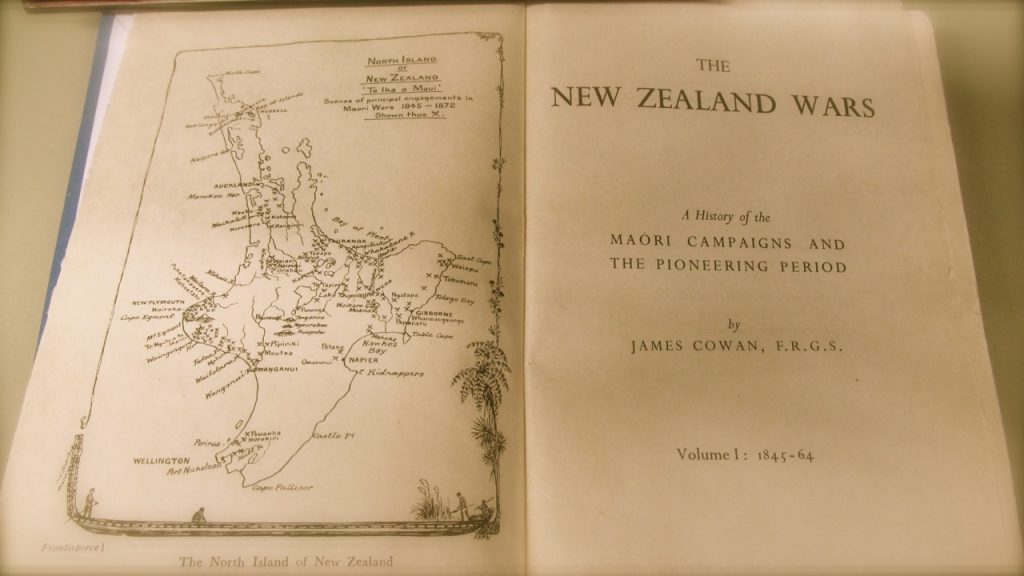

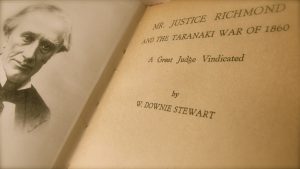

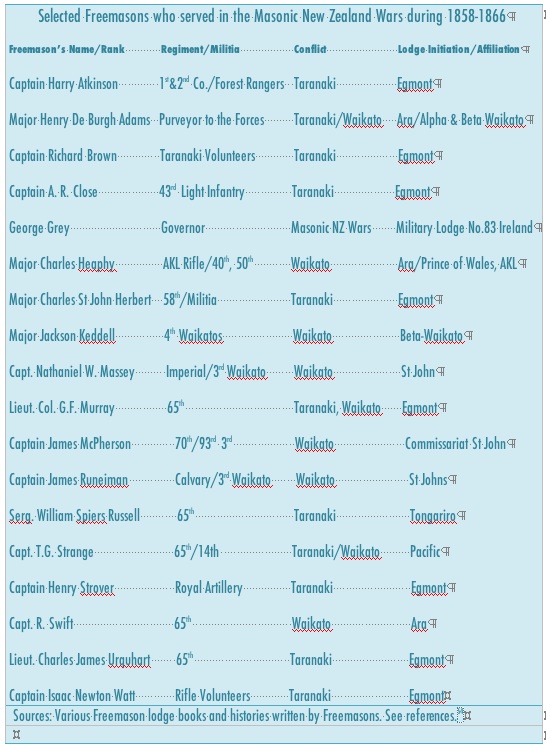

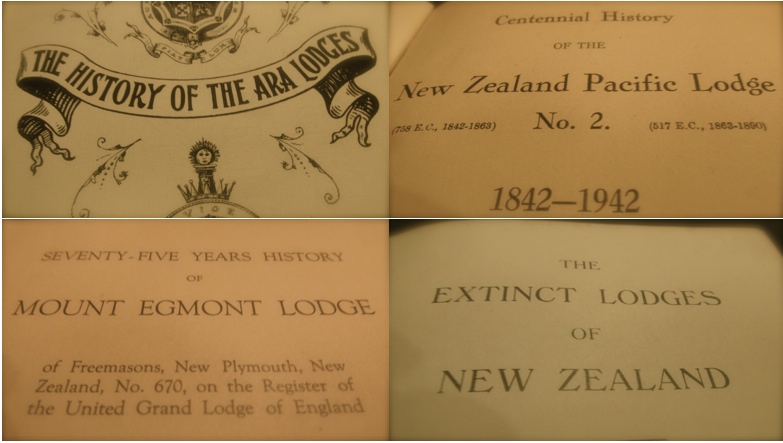

Historians of the New Zealand Wars, often categorized as happening between 1845-1872, with 13 years of uneasy ‘peace’ laced with acrimonious skirmishes, and of New Zealand’s formative history have largely overlooked the instrumental role that Freemasonry played to absorb New Zealand into the British Empire. While some prominent Freemasons are mentioned in the 1940 edition of the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography published by the Department of Internal Affairs, this ‘Who’s Who’ compendium of New Zealand hardly captures the brotherhood’s secret network of key players.

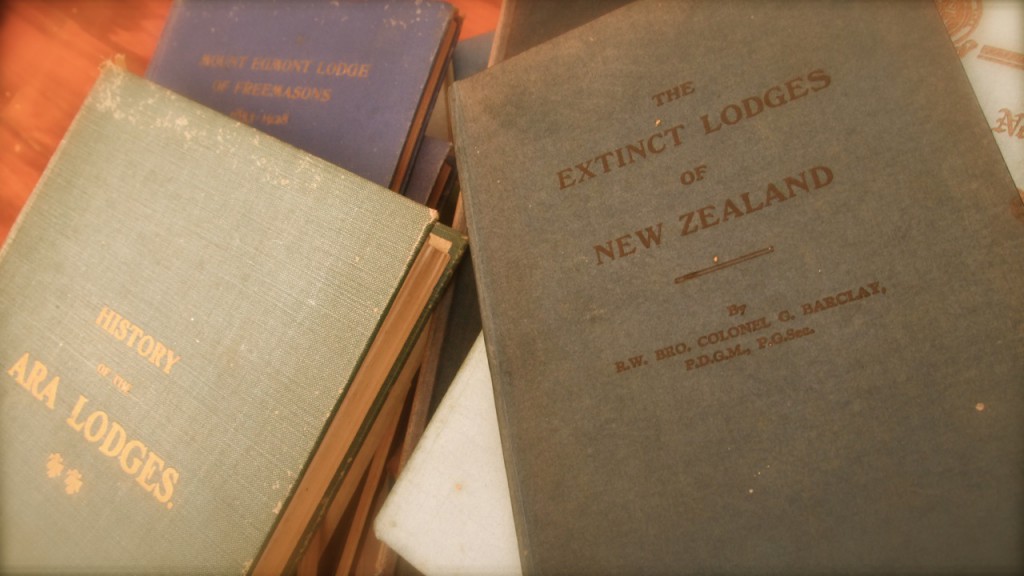

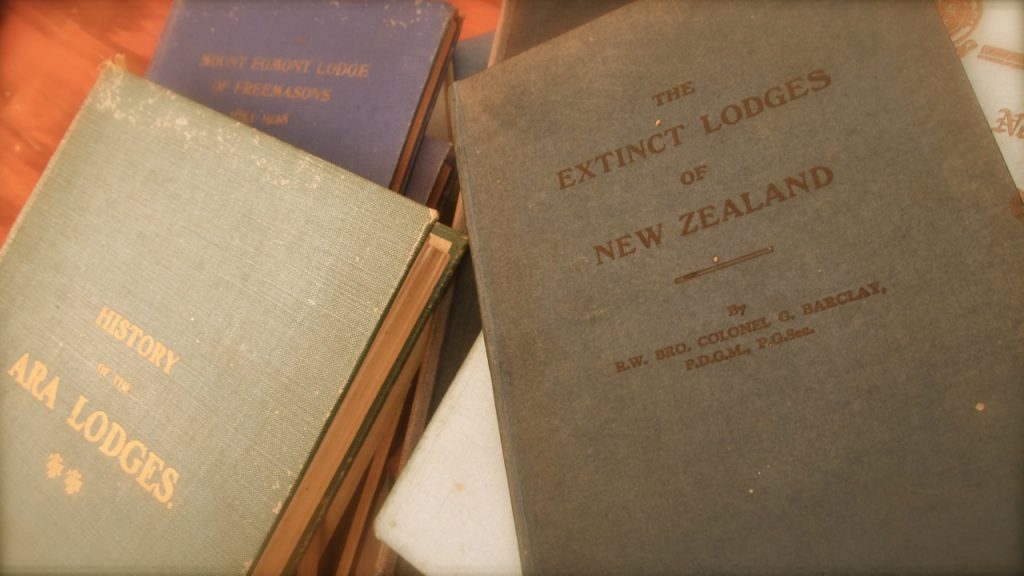

Freemason papers, proceedings and their lodge books, many of which were not intended for public eyes, provide some details of their esteemed brethren, ‘noble’ heroes and fallen brothers. Together, these hard-to-find works provide partial lists of those who fought in the various regiments, volunteer militia and forest rangers, as well as those embedded across New Zealand’s hymn-singing protestant political-commercial-military establishment.

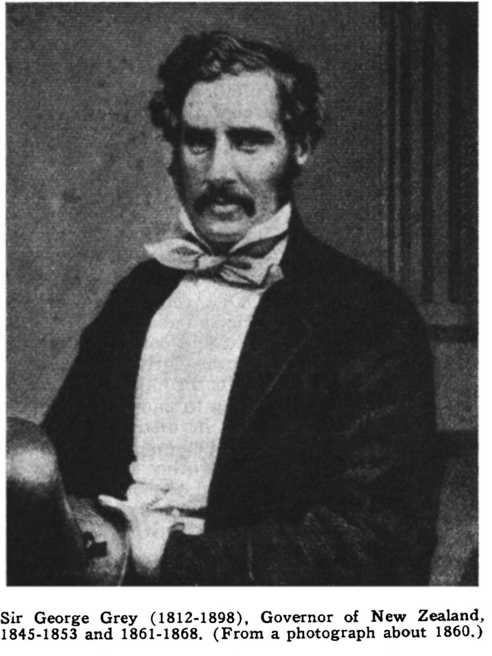

But, they fail to capture the big picture narrative of Freemasonry being used as a secret imperial mechanism of expansion, as well as exploiting their own fraternal brothers as hapless musket, axe and patu fodder against a clever, resourceful and spirited native race. To be super-clear, Māori deserved far-better respect, compassion, and full disclosure following the horrors of the Musket Wars (1806-1845); the brazen fraud of Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson and his Crown agents to trick Māori chiefs to sign Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840; and Freemason Governor Bro. George Grey’s gambit during his first governorship to play the longer ‘Great Game’ of empire, by waiting until migration had evened-out the balance of population between colonists and natives.

Here I sketch the conflict as a ‘necessary’ and ‘justified one’ from the standpoint of unseen oligarchs that ruled the ‘British Empire’ through the secret society – Freemasonry. Oligarchs are super-rich tax-averse, land-grabbing, viscous-minded, enslaving people who use their enormous economic wealth to steer the trajectory of whole societies, particularly when they act as a cohesive coalition, or an oligarchy.

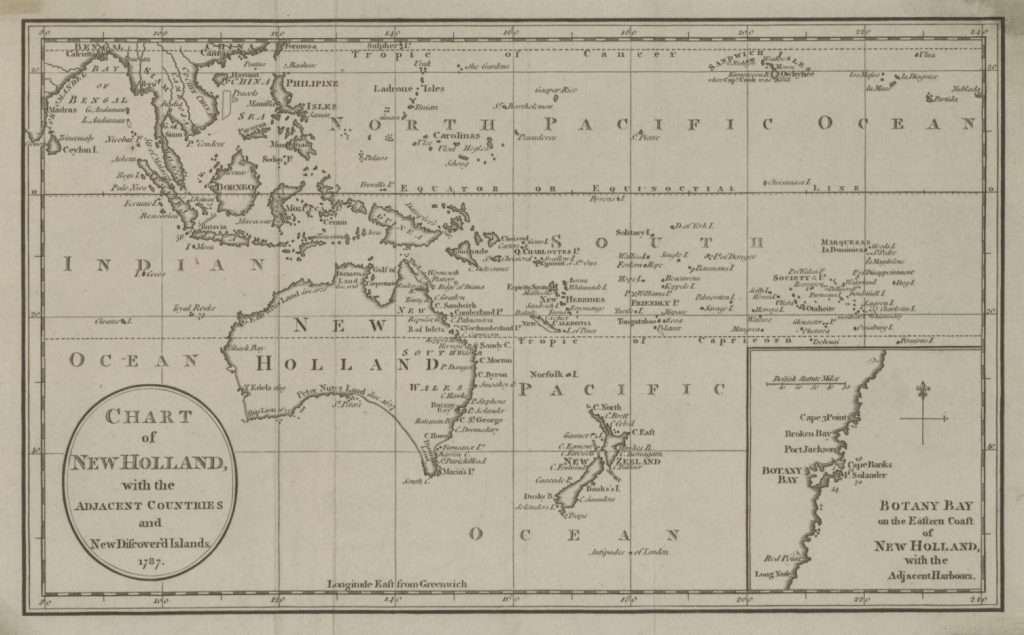

The primary purpose of the conflict, which I initially termed the Masonic New Zealand Wars, occurred across several regions in the ‘North Island’, was to destroy the Māori communal economy, with which the colonists could not compete. But, I have subsequently come to see the conflict as the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872, because it was primarily a revolutionary war to upend the social order of Māori. This war was the consolidation stage to realize the utopian vision articulated by Freemason Bro. Captain James Cook, who was instructed by the British Admiralty to annex any new great territories before other rival cannon powers.

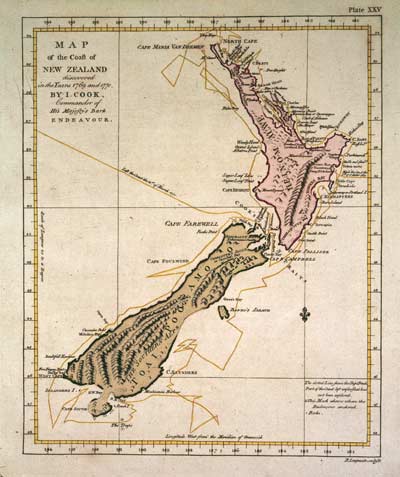

Bro. Captain Cook viewed Nieuw Zeeland as an ideal resource-rich base for the British Masonic Empire in the South Pacific Ocean due to its geographical isolation in that ‘quarter of the world’. It turns out that Bro. Cook’s claims of possession over New Zealand in the name of King George III were an activation of the Doctrine of Discovery, which was a legal code that the European cannon powers applied to territories of the ‘New World’ to claim as colonial possessions.

Therefore, the revolutionary war of 1860-1872 was inflicted to consolidate the territory of New Zealand as a British Masonic State. The capacity for Māori to continue as the major domestic trading partner would be wrecked by activating the ‘conquest element’ of the Discovery Doctrine to establish substantive sovereignty over the ‘soil’.

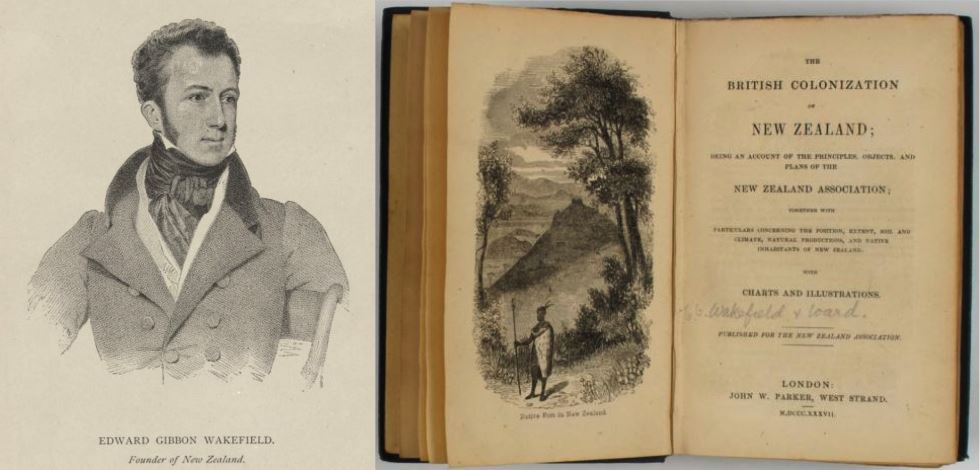

The vision to colonize New Zealand was advanced by Freemason Bro. Lord Durham, born John George Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, who was a founding member and chairman of the land-swindling New Zealand Company. Lord Durham — who was initiated at Granby Lodge No. 124, in 1814 — was provided with an office by Francis Thornhill Baring, 1st Baron Northbrook, whose family owned the Baring Brothers merchant bank. Baring was a member of the British Parliament from 1826 to 1865. He had attended sessions of the Committee on Colonial Lands in 1836, wherein the ‘New Zealand Question’ was discussed.

Getting legislation passed in the British Parliament to colonize New Zealand would have attracted the attention of the French, the Americans and the Vatican, thereby risking the enterprise to gain a far-flung colony on the cheap. If the British Masonic Empire failed to complete the sovereign title claim to New Zealand initiated by Captain Bro. James Cook, that failure of action would further threaten the transmarine empire’s standing.

Lord Durham’s vision was given intellectual shape by Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s ‘art of colonization’ doctrine in his 1837 book, The British Colonization of New Zealand. In early 1837, Wakefield founded the New Zealand Association at the suggestion of Baring, as Helen Taft Manning recounted in her 1972 essay entitled, “Lord Durham and the New Zealand Company”. However, in 1838, Wakefield travelled with Lord Durham to Canada to report on two rebellions that occurred in 1837, leading Durham to recommend responsible government.

Let me retrace the conspiracy to plot the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-72 as an exquisite example of Masonic-Protestant revolutionary machinations that culminated in an inevitable consolidation stage.

As such, to implement a violent consolidation stage of Bro. Cook’s utopian vision, the colonists’ would need to impose their British Masonic masters favoured private political system for social control. Such control would consolidate the territory that Freemason Bro. Captain James Cook, Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson, Captain Stanley and Police Magistrate Bro. C. B. Robinson had slyly annexed for the British Empire with quills, ink, paper, poles, flags, propagandist prose and other Discovery Doctrine devices, rituals and tactics. This private political system was Masonic Colonial Capitalism, which was inherently oligarchic, and this meant it used coercive economic mechanisms at the disposal of wealthy coalitions of Freemasons to control people.

To establish Masonic Colonial Capitalism — and therefore, a British Masonic State — a period of ‘primitive accumulation’ or conquest of ‘land capital’ was needed. The expected dispossession of Māori from the ‘native land estate’ through confiscations during and after the ‘native troubles’ enabled the start-up Bank of New Zealand to formalize a debt-enslavement monetary system of private credit ‘loaned’ as national debt, backed by soon-to-be-stolen, swindled and stealthily snookered land, resources and native human collateral.

However, Freemasons have left their marks for historians to retrace their moves.

The Masonic Brotherhood often embedded the number 13 and multiples of it into events, appearing as mundane data in dates, quantities and locations. In occult numerology, the number thirteen represents ‘unity’ and ‘fraternal love’, as the occultists W. Wynn Westcott in his work, Numbers: Their Occult Power and Mystic Virtues, and Aleister Crowley in his book, Liber 777 — both asserted. More practically, Freemasons embedded 13 and its multiples into events to find one another, to signal they were advancing the ‘great game’ of empire together, and to caution other Freemasons not to investigate too hard when scandals broke.

This essay sketches Freemasonry’s secret role in the primitive accumulation of the Māori native estate during the peak period of the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War — 1860 to 1866.

Primitive Accumulation to Overcome the ‘Natives Troubles’

Freemasons appointed their members of the brotherhood to key positions in the New Zealand Colony. Despite the prominence of many of their members in public life, Freemasons were careful to keep the role played by their secret network largely out of history.

The secrecy worked as a weapon of intelligence, solidarity and plotting.

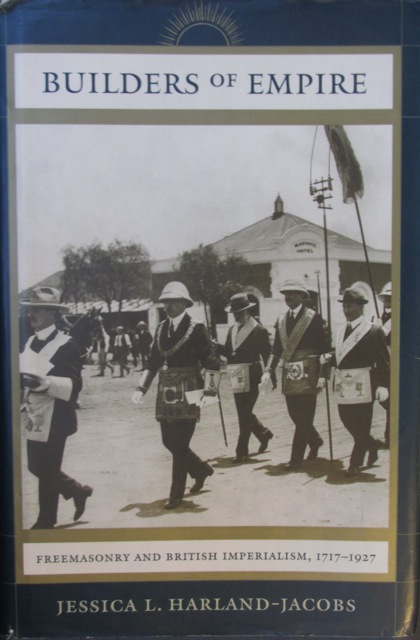

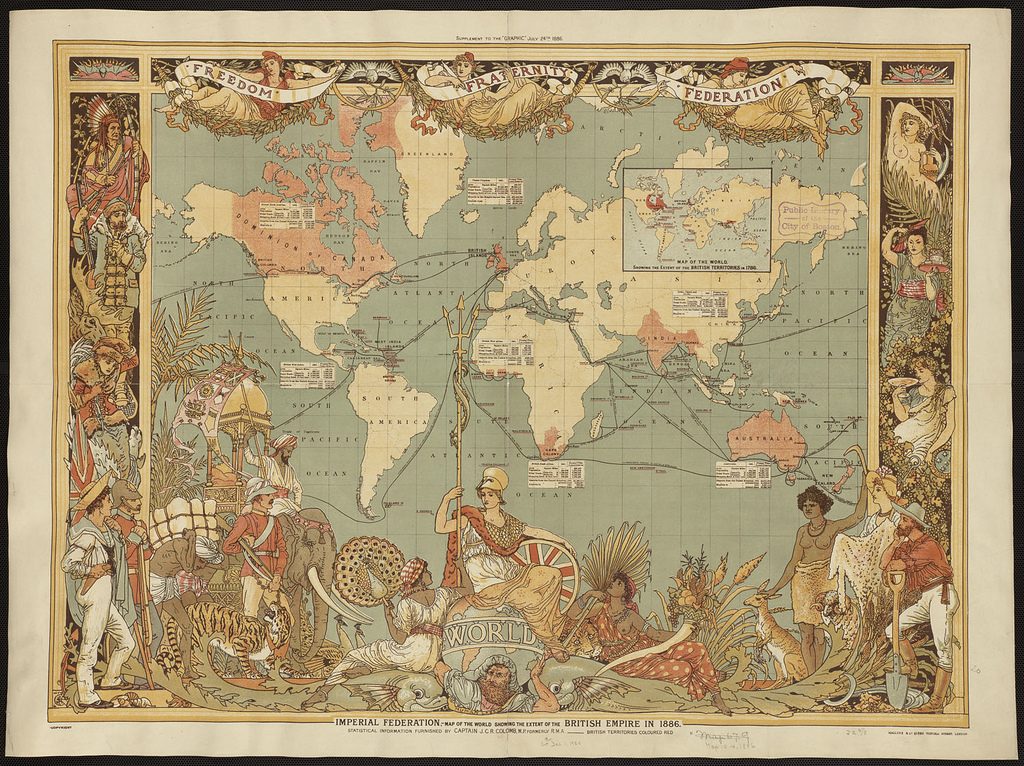

The primary secret mechanism by which the British Empire spread throughout the ‘New World’ was through the secret society of Freemasonry. In turn, Freemasonry was spread mostly through the military regiments, including the navy, as Jessica Harlands-Jacobs showed in her book, Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927. [2] Harlands-Jacobs, who accessed numerous libraries for her PhD including the Royal Archives, claims that Freemasonry merged with the British Government and the British Monarchy during the 1790s and over a period of three decades re-invented its political leanings and ideology.

However, Builders of Empire focuses a lot on how Freemasons lived up to their cosmopolitan ideology when it came to inclusiveness toward indigenous peoples and former slaves in the colonies, or in their exclusion of women and Catholics from Freemason lodges in the 130 year period of imperial expansionism examined. As a study of British Masonic Imperialism, Harlands-Jacobs’ work does not reveal the network of the secret brotherhood and their roles in the British Empire. Builders of Empire, therefore, leaves the legitimacy of the British Monarchy, Parliament, the City of London Corporation, the Bank of England, the Church of England, the Temple Bar, the Royal Society, and British Freemasonry intact because it avoids revealing the parallel political system, insider trading and structural dispossession through swindle, stealth and struggle by Freemasonry.

Due to these strategic shortcomings, Builders of Empire masks how two British Empires were layered, and why. There was the Christian British Empire, complete with missionaries exercising ‘soft-power’ to civilize ‘the natives’. And there was the hidden British Masonic Empire hell-bent on world domination, as Nicholas Hagger found in his epic study, The Secret History of the West, that modelled for the patterns of revolutions, how secret societies plotted them and reasons for the subterfuge. Their hell-bent vision competed with a rival Brotherhood, French Templar Freemasonry. British Freemasonry was Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry, which founded a United Grand Lodge in 1717 to unify English resistance to Jacobite Templar Freemasonry, that formed around the Scottish Stuart dynasty, who were formally and permanently banished the same year from the British Isles. It was at this point, in 1717, when Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry came to rule over the British Monarchy and the Church of England, after having successfully achieved a political and business merger with the Dutch in 1688.

More specifically, the ‘Glorious Revolution of 1688’ – which saw Prince William of Orange and his consort Mary wrest control of the British throne from King James II after they landed at Torbay, near Brixham, Devon, on November 5 with 250 ships – was secretly bankrolled by English Rosicrucian Freemasons, the Bank of Amsterdam, and Amsterdam Jews, and was part of a two-hundred year Venetian project to takeover Britain. Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry is a revolutionary force committed to forging a universal empire under the rule of one monarch, while French Templar Freemasonry developed into a revolutionary force committed to forge a universal empire under the rule of one federal republic.

Naturally, these secret Utopian objectives that underpinned the real English and French Empires were not mentioned to rangatira in the discussions that took place around the signings of the Treaty of Waitangi. The British were playing for time, knowing that at some point conflict would occur. The fraudulent English version of the Treaty would serve its propagandist purpose because it could be construed that Māori chiefs voluntarily surrendered sovereignty without battle, even though the Māori language version retained rangatira sovereignty over Māori, lands and other resources that Māori did not sell. Māori would be cast as savage rebels for resisting incursions, pressures to sell and destruction of crops and other incessant acts of Masonic subversion.

[Editor’s Note: See the Snoopman’s Deep History of Waitangi: The Queen Victoria Connection for his account how the British wrested paper sovereignty by a ‘Colonial Law Track’, while the 1840 Waitangi Treaty worked as a red herring literary device to avoid authorization from the British Parliament, legal challenges in English courts and embarrassment for the British Monarch. A summary Deep History of Waitangi conveys the key details of the ruse].

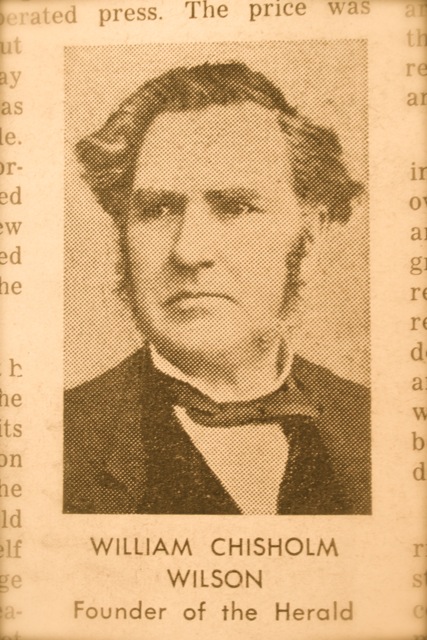

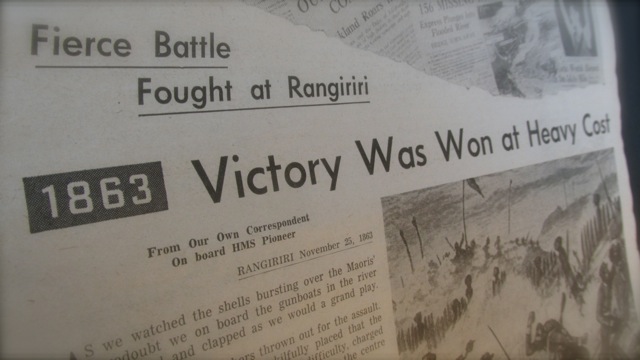

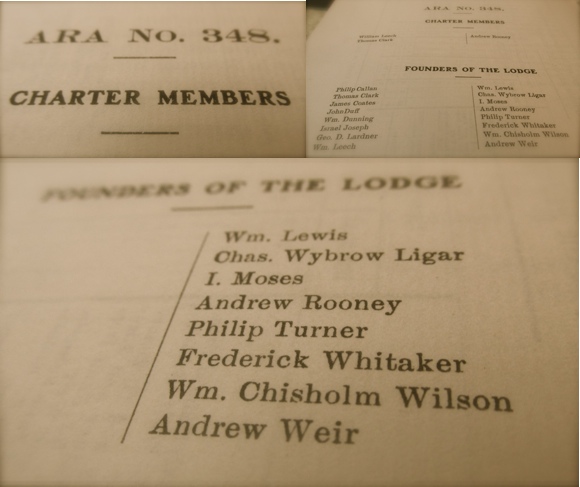

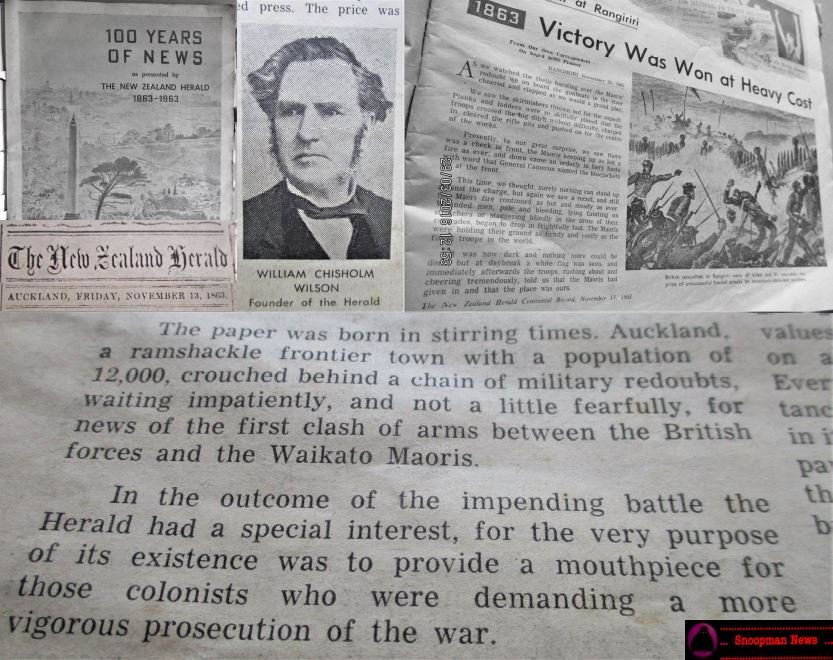

In the colonial era, the propagandist task of agitating for war fell to the newspapers in the New Zealand colony, which during the crucial 1860-1866 period of the New Zealand Wars included the Masonic-controlled newspapers such as the Taranaki Herald, The New Zealand Herald and the Wellington Independent.[3] The founder of The New Zealand Herald was Bro. William Chisholm Wilson, who also was a founder of New Zealand’s first Freemason lodge, the Ara Lodge,[4] while the Taranaki Herald was founded by Bro. Garland William Woon;[5] and the Wellington Independent, was owned by Bro. Thomas Wilmor McKenzie[6] and whose first editor was Dr. Bro. Isaac Earl Featherston, who while wearing his Superintendent of Wellington hat sarcastically said in 1856, “Our plain duty as good compassionate colonists is to smooth down [the Māori race’s] dying pillow”. [7]

The following excerpt from The New Zealand Herald’s very first editorial of 13 November 1863, sells the propagandist line that Māori were in rebellion against British law around the peak period of the New Zealand Wars. The Herald editors of colonial times wrote:

“the rebels should be energetically dealt with, the war has been one of their own compelling. They commenced it with cold-blooded deliberate assassinations. They are following up with stealthy murders of defenceless women and children. The fruits of a life of industry are the sacrifices of their vengeance. Agriculture perishes. Commerce languishes. Enterprise stands still. And a great and glorious country runs to ruinous waste until the murderer and marauder shall be imperatively taught that life and property must be preserved and Law and Order maintained inviolate”.

– The New Zealand Herald, Friday 13 November 1863. [8]

Māori were not in rebellion for refusing to sell any more land in 1860 – as they had been widely and viciously slandered as justification for the First Taranaki War — and at a time when the Māori land estate had been reduced to 21.4 million acres out of 66.4 million acres. There was no rebellion for the simple reason that Māori never agreed to relinquish their right of self-determination and sovereignty.[9] This refusal by Māori to sell more land, which emerged as a consensus in 1854, led to Pākehā settlers to conspire to restart the New Zealand Wars in 1860.

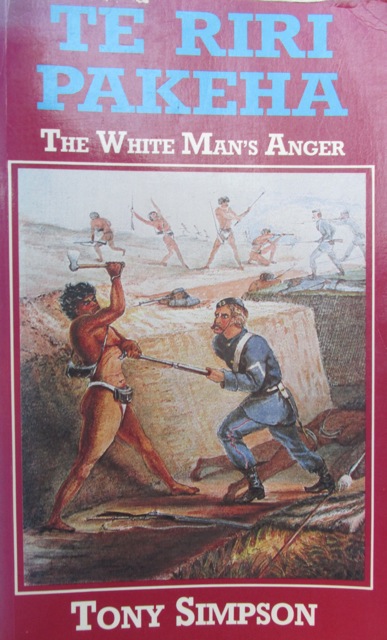

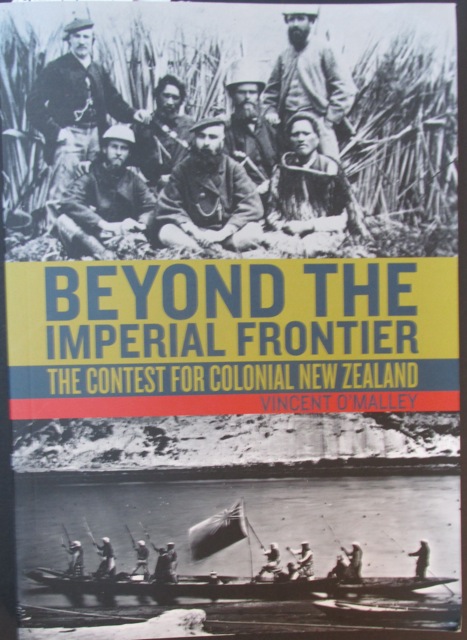

According to Marxist theory, capitalism cannot be established without a prior period of primitive accumulation, or conquest.[10] Indeed, at the time of hostilities breaking out in Taranaki in March 1860, Māori had 53 ships and the white settler population simply could not compete with the Māori communal economy. Destroying the Māori communal economy, argued Tony Simpson in Te Riri Pakeha: The White Man’s Anger, was the driving motivation of key colonialists.

James Belich in The New Zealand Wars, stated the main British objective was to assert sovereignty because “to oppose sales was to oppose the extension of British sovereignty and to defend Maori autonomy”. In Two Peoples, One Land: The New Zealand Wars, Matthew Wright asserts that the structural pressures of settlement and government power drove the break-out of war in 1860 and that responsibility for the Waikato War of 1863-64 lay with Governor Grey.

Also unbeknown to Māori at the time of signing the Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi, the British government and its colonial agents had been systematically deploying a secret international law agreement since Freemason Bro. Captain Cook’s first voyage. Known as the Doctrine of Discovery, this secret piece of international law was reached between European nations at a time when they were forming empires since the 15th Century, and was designed to mitigate the chances of competing nations making expensive war with each other. It was thought it would be easier to gain territory off indigenous peoples’ cast as ’savages’ rather than from their more technologically even European competitors.

Through the application of another international law doctrine – terra nullius – the natives’ of the ‘New World’ were considered to lack full political rights because they were not Christians busy cutting vast swathes of forests for sheep and cattle to graze and therefore they were deemed too ‘primitive’ to be considered ‘sovereign’.[11] Not surprisingly, ‘colour prejudice’ as a “conscience-salving colonial doctrine” surfaced around 500 years ago, coinciding with the emergence of the European empires.[12]

Civilizations only become empires when they turn aggressively expansionist and engage in imperial wars to support an oligarchy’s insatiable appetite for wealth accumulation, control of technologies and other resources to out-compete the empires of rival oligarchies.[13] In New Zealand’s case, the Lords of the Admiralty were very clear in their secret instructions to Bro. Captain James Cook, which were not published until 1928, that the British Empire had to beat other rival powers seizing any new great territories. Bro. Captain Cook viewed Nieuw Zeeland as a resource-rich base for the British Masonic Empire in the South Pacific Ocean. Indeed, the British navy had obtained kauri spars from New Zealand in 1820 for His Majesty’s Ships.

Masonic Bros in the Closet of Empire

To instigate the Conquest stage of empire (also the Discovery Doctrine element) somewhere as the 1850s were drawing to a close, the Pākehā settlers had to cast their wedge of war in a way that gave them the appearance of occupying the so-called moral high ground. Here, I sketch some key events that formed a wedge of war, as I call it, toward the thin end where hostilities are triggered, and propaganda amplifies so that the ‘enemy’ is blamed for the final most visible deeds that are conveniently remembered as the causes of the conflict. In this conquest over the North Island, I trace the hidden hand of the secret Order of Freemasons.

To this end, in February 1858, Taranaki settler and Native Affairs Minister Christopher William Richmond wrote to the New Plymouth Resident Magistrate and Freemason Brother Isaac Newton Watt, outlining a policy of structural entrapment to lure Māori into a position that could be construed as “high treason”. Christopher William Richmond wrote:

“Should anything happen, what the magistrates have to do to place the government technically in the right is to bring the contumacy [rebelliousness] of the natives up to the point of actual defiance of the government, ‘i.e. high treason.”[14]

In essence, Richmond the politician outlined a structural entrapment policy to Bro. Watt – who was also a founding member of the New Plymouth Masonic settlers’ Mount Egmont Lodge, and future captain in the Taranaki Rifle Volunteers– whereby officers of the courts were to act as agent provocateurs.[15] In 1858, the Militia Act was passed, which made it legal for settlements to form voluntary corps. This Act came after Taranaki settlers had appealed to the Colonial Government to take action to settle the ‘Land Question’. The Richmond’s were inter-married with the Atkinson family, among them Bro. Captain Harry Atkinson who was initiated into Freemasonry on May 11 1864 and fought with the Taranaki militia in both Taranaki Wars, later became New Zealand premiere.[16]

Following three large hui in the mid-to-late 1850s, which took place in Taranaki in 1854, Taupo in 1856, and the Ngaruawahia in 1858, Māori resolved to halt any further sales over millions of acres of land that they held tenuously to. In June 1858, the Waikato iwi had instilled the first Māori King, chief Te Wherowhero who became Kingi Potatau, and he placed a tapu forbidding the sale of any more land in the Waikato region.[17] Meanwhile, tensions between the Taranaki settlers and various Māori iwi and family groups (or hapu) had been brewing and erupting since Governor FitzRoy overturned Commissioner Spain’s decision to award the land-swindling New Zealand Company 60,000 acres in 1844.[18]

the first Māori King, chief Te Wherowhero who became Kingi Potatau, and he placed a tapu forbidding the sale of any more land in the Waikato region.[17] Meanwhile, tensions between the Taranaki settlers and various Māori iwi and family groups (or hapu) had been brewing and erupting since Governor FitzRoy overturned Commissioner Spain’s decision to award the land-swindling New Zealand Company 60,000 acres in 1844.[18]

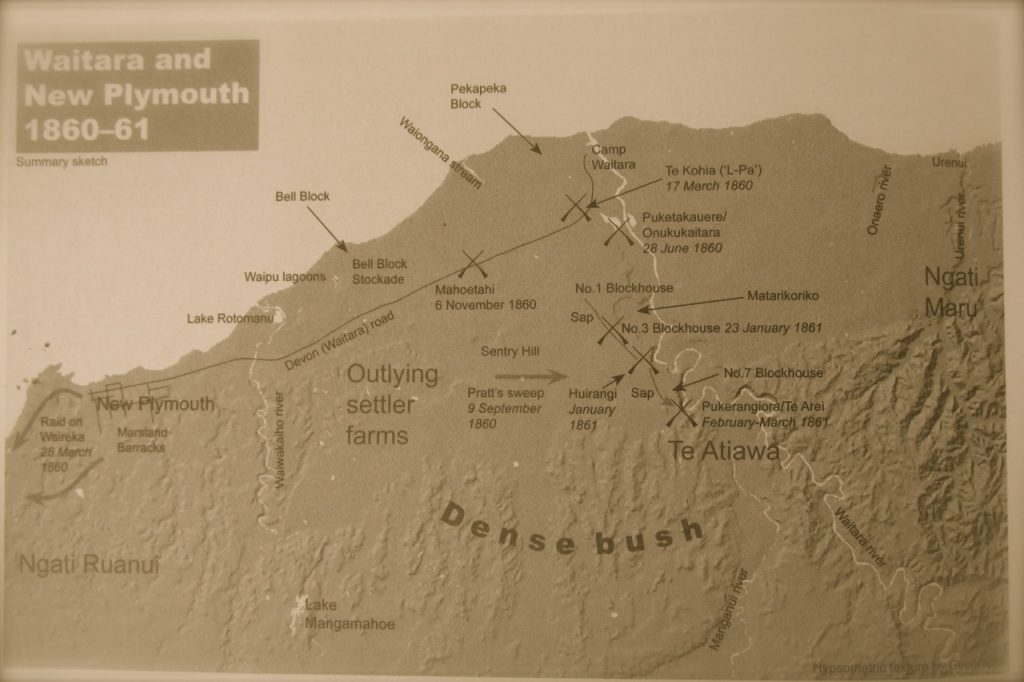

The Taranaki settlers, who had no inclination to learn Māori communal land-use practices, or cultivation, hunting and foraging techniques and dietary practices, resented that they were ‘hemmed in’ to 3500 acres, awarded by FitzRoy, which included the coastal settlement town of New Plymouth. Jealously eyed was the 600-acre river-side village and fertile cultivated gardens at Waitara, which was communally-owned by the Atiawa iwi. The British colonists coveted Atiawa’s fertile riverside land and wanted to construct a river-port at Waitara, since New Plymouth, which lay 10 miles to the south, lacked a harbour.[19]

The anti-land selling stance that Māori had taken was an affront to British Masonic imperial ambitions. Indeed, the Colonial Government’s Commissioners for Land Purchases had pursued a stratagem to wrest land from iwi and hapū by gleaning information, targeting those Māori most willing to sell and using successive sales to encourage further purchases and create disunity among Māori. Bro. Donald McLean undermined this widespread opposition by referring to Māori communal ownership as a ‘Land League’. This was a loaded term that was used by landed gentry of England and Ireland as propaganda to undermine tenants croppers’ rights to occupy land or trade union attempts to exert communal interests, at a time when the privatization of land through the Enclosure Acts were used as a mechanism to force people to find work in the industrializing cities. In Taranaki, the District Land Commissioner, Freemason Bro. George Sissons Cooper, had pressured chief Rawiri Waiaua to sell a disputed wheatfield north of New Plymouth, a sale that chief Katatore was opposed to eventuating.

When Chief Rawiri Waiaua attempted to prepare the land for surveyors, he ignored the warning shots of chief Katatore, and was killed in a brief battle by Katatore’s party. This incident on 3 August 1854 led to years of reprisals, galvanized attitudes around the ‘Land Question’, and provided settlers with the opportunity to categorize Māori as ‘friendly’ or ‘hostile’, depending on whether or not they were willing to sell land.

In this uneasy atmosphere for Māori and Pakeha alike – and soon after Richmond’s outrageous letter was sent to Bro. Watt – a meeting to discuss the formation of a militia took place in the New Plymouth Freemason’s Mount Egmont Lodge in early 1858. Among the committee of five men formed at this Masonic Hall meeting, which occurred a full two years prior to the commencement of the First Taranaki War, were Bro. Richard Brown, land agent, merchant and co-editor of the Taranaki Herald; settler Bro. William Halse, and farmer Bro. Harry A. Atkinson, who became a corporal in the First Company of Taranaki Rifle Volunteers and Captain in the Second Company.[20] James Crowe Richmond, the brother of the Minister of Native Affairs, also volunteered for this militia committee, and the Taranaki Rifle Volunteer Company was formed on 13 January 1859.

By 1859, Governor Thomas Gore Browne decided to personally intervene with a trip to the Taranaki district, which had a history of ambushes, fighting and murders between settlers and Māori. On 8 March 1859, Browne, who Maori called Governor Angry Belly, convened a meeting between Taranaki iwi in the grounds of the Native Office in New Plymouth. The governor made a speech that warned that the fighting, particularly on settler land had to stop, or harsh measures would follow. As former Radio New Zealand producer Tony Simpson put the situation in his 1979 book, Te Riri Pakeha: The White Man’s Anger, “[i]f he [Browne] had left matters there he would have done no harm.”[21] The trouble was not simply that Governor Browne was a stupid man who blustered when he did not understand a raruraru (or problem), in place of asking questions.

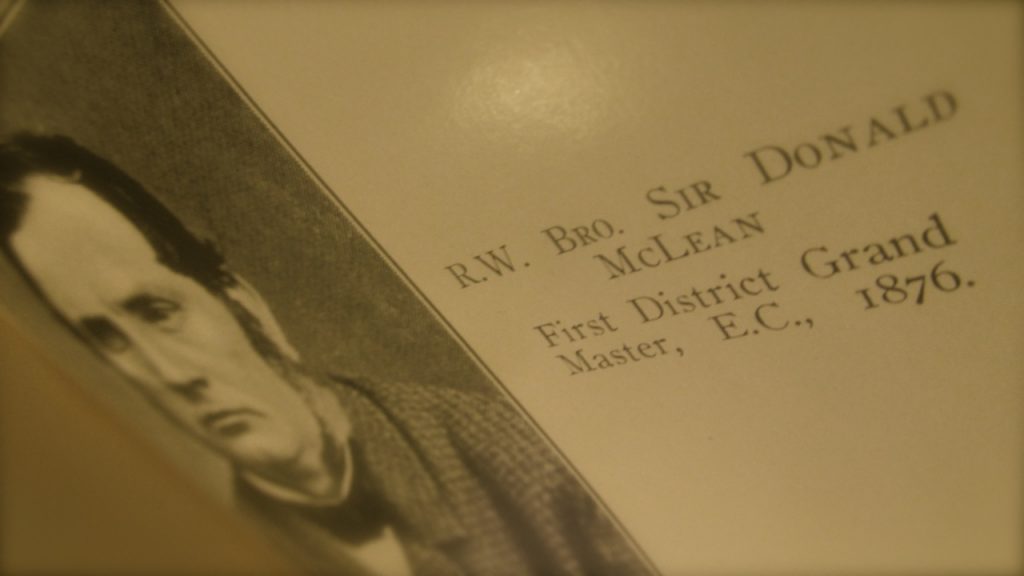

But, the real raruraru was that there was a very cunning Freemason in his midst: Bro. Donald McLean.

An accomplished land swindler, Brother McLean, who had been promoted to Chief Land Purchasing Commissioner in 1853 by Bro. Governor George Grey in recognition of his instrumental role in duping Māori into selling 30 million acres (or approximately 12,140,569 hectares) of the South Island [nearly the entire landmass] over a period of eight years for a symbolically sneaky sum of £13,000.[22] (This purchase of 30 million acres was a thousand-fold biggering of the purchase of 30,000 acres made at Akaroa by French Freemason and whaler Captain Bro. Jean Langlois in 1838, which culminated in an attempt at French Templar colonization in New Zealand in August 1840.

Thus, Bro. Governor Grey was signalling that substantive sovereignty over the South Island – Te Wai Pounamu – had been gained by English Rosicrucian Freemasonry over French Templar Freemasonry, and by the end of his Governorship, 130,000 km2 or nearly 33 million acres, had been swindled from Māori). [23] Bro. McLean was familiar with the tensions over land in Taranaki, including Waitara, the pressure to obtain it were present during Bro. Grey’s first Governorship, who had remarked in 1848 that “no land in Taranaki at all will be obtained without war”.

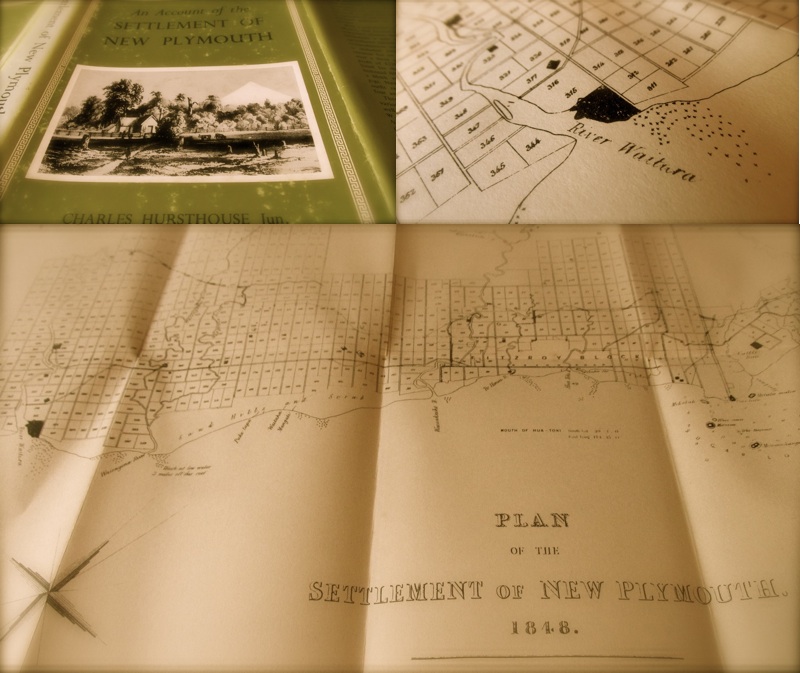

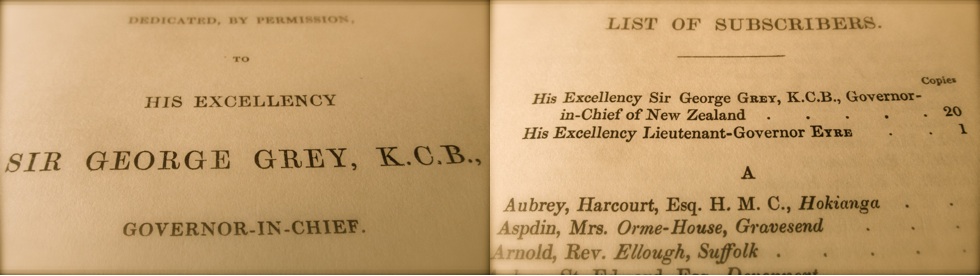

Indeed, Governor Bro. Grey was the lead sponsor of a 1849 book titled An Account of the Settlement of New Plymouth, which cast Waitara as part of the New Plymouth settlement with a map. (Other leading subscribers of this Charles Hursthouse book were the New Zealand Company of London, who paid for 100 copies; 12 copies were subscribed by Commissioner for Crown Lands Bro. Francis Dillon Bell; and Colonel Bro. William Wakefield, principal agent for the New Zealand Company in Aotearoa, who pre-paid for 5 copies, and under whose captaincy the New Zealand Company outrageously laid claim to 20 million acres in the first few months of the Tory’s land-swindling voyage of 1839 and 1840. The Wakefield and Bell families were connected by marriage).

At the 8 March 1859 meeting with Taranaki iwi in the grounds of the Native Office in New Plymouth, Bro. McLean, who had carefully translated Browne’s speech into te reo Māori, also advised Governor Gore Browne to finish with comments about what the governor deemed acceptable protocols on the vexatious matter of land sales. Browne’s remarks on land sales provoked an Atiawa sub-chief, Teira, to leap to his feet to offer to sell a significant chunk of land at Waitara. Bro. Donald McLean and the Native Affairs Minister C.W. Richmond had calculated that Teira would literally leap at the chance. After consulting with Bro. McLean and Richmond, Governor Browne accepted the offer on the condition that Teira could prove clear title.

During Bro. George Grey’s first governorship, he had twice refused to accept the sale of the Waitara block presently being offered because he recognised that it belonged to Atiawa as a whole, and not to Teira alone. Grey was also aware that Teira and chief Wiremu Kingi Te Rangitake had an emotionally-charged history that dated back to Teira missing out on marriage. Bro. McLean, who was well-versed in Māori custom, culture and conflicts, well knew that Teira was exacting revenge upon Kingi and that Teira had offered the land for sale back when Governor Bro. Grey had the ‘final’ say.[24]

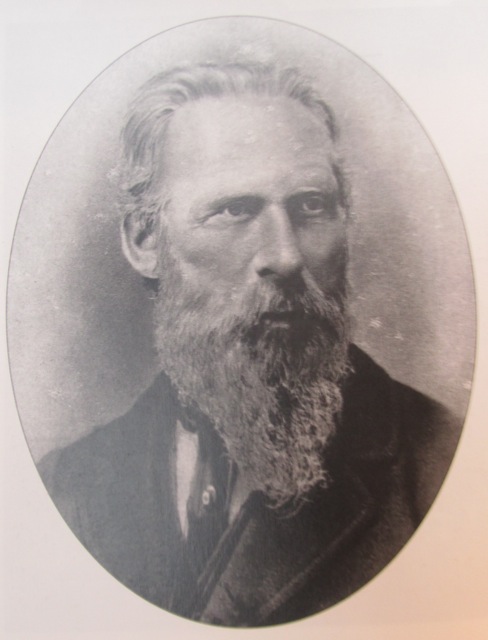

Skilled Swindler: Freemason Bro. Donald McLean, Chief Commissioner for Native Land Purchases.

On 28 November 1859, Richmond authorized payment for the sale of the Waitara block after Bro. McLean’s deputy Robert Parris, who became a major in the Taranaki militia, wrote to the Minister of Native Affairs to say that Teira’s title to Waitara was clear. The amount was 100 sovereigns, or £100, which was precisely the amount of debt that Teira just happened to owe to Parris. After eight months at an impossible task to prove Teira’s claim was legitimate, Parris ‘achieved’ this impossibility by deploying an impossible explanation. The Deputy Commissioner for Native Land Purchases asserted that Teira’s claim to title was supported by what he had “gathered from disinterested natives”[25]. In 1859, there was no such social group anywhere in Taranaki, and nor in rest of the imaginatively named ‘North Island’ (and to be fair, in Te Wai Pounamu), that could be described as ‘disinterested natives’ – except in the transmission of a legal fiction.

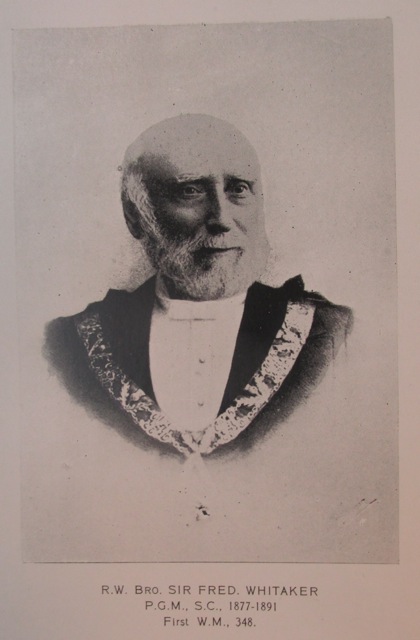

The Attorney General, Freemason Brother Frederick Whitaker (1812-1891), advised the Colonial Government that the Crown had acquired title properly.[26] Whitaker claimed he based this advice on Freemason Brother Donald McLean’s assessment (1820-1877), a wealthy landowner, administrator and negotiator who spoke fluent Māori.[27] However, Bro. McLean had absconded from Taranaki immediately to shore up Teira’s offer to sell by seeking approval from Atiawa people that still lived near Queen Charlotte Sound, having fled incursions by Te Rauparaha and Te Wherowhero during the Musket Wars. Bro. McLean’s sudden departure left his deputy, Robert Parris to make the impossible seem plausible.

Furthermore, Attorney General Brother Frederick Whitaker, a founding Anglican Freemason of the first New Zealand Masonic lodge to be granted a dispensation on 5 September 1942,[28] was already by this time a land speculator who claimed to understand ‘Maoris’. (Governor Col. T. Gore Browne said most of Colonial members of parliament knew nothing about the native people. Browne himself understood little of Te Māori customary land tenure laws).

Having set this horrendous legal fiction in motion, on 25 January 1860, Christopher William Richmond – who was a member of the House of Representatives and the New Plymouth Provincial Council – ordered land surveyors into Waitara. Predictably, on 20 February elderly Māori women and men pulled out the survey pegs. (Predictable, because Māori had been doing this since 1840 when the land-swindling New Zealand Company’s surveyors had set their pegs on land where Port Nicholson in the capital city, Wellington, is today).[29] The survey pegs symbolized the intention to forward the Discovery Doctrine’s element of ‘Actual Occupancy and Current Possession’.[30]

Applying historian Carroll Quigley’s Civilization thesis,[31] the New Plymouth settlers sought to possess Waitara because occupation would provide the settler’s with fertile land next to a river suitable for a port, which would give them the capacity to produce a surplus, a necessary element in establishing ‘Civilization’. Wiremu Kingi did not want war, but instead wanted to go to court, where the shakiness of the settler’s position would have been laid bare – on the record.[32] With these ingredients in the settlers’ calculus, events were quickening at the thin end of this wedge of war.

Meanwhile, the resident military officer wrote to Chief Wiremu Kingi of Waitara warning him that resistance was rebellion. The survey party was harried by old women and children, a clever move in non-violent peaceful resistance that forced the surveyors to abandon their tasks. However, martial law was promptly declared on 22 February and on 5 March troops arrived up the Waitara River. Four companies of the 65th Regiment equipped with artillery set out to occupy Waitara. Wiremu Kingi had abandoned Waitara before the troops arrived.

The survey of Waitara was completed on 13 March 1860. Three days later, the Imperial and Colonial forces were surprised to find that Kingi’s men had built an L-shaped pa in a single night on the disputed Waitara block. A 300 man force, under the command of Major Bro. Charles Herbert, marched to Waitara on March 17.

The 1st Taranaki War had begun after 13 years of relative peace.[33]

Native Minister and Taranaki settler Christopher W. Richmond – who had written in February 1858 to the New Plymouth Resident Magistrate and Freemason Bro. Isaac Newton Watt, outlining the structural entrapment policy to lure Māori into a position that could be construed as “high treason” – now relished the conflict at Waitara. Richmond wrote:

“It has long been manifest that in the first attempt to enforce obedience to the governor’s decision on any question affecting the natives might bring the disaffected tribes to the point of rebellion. An occasion has now arisen in which it has become necessary to support the governor’s authority by a military force. The issue has been carefully chosen – the particular question being as favourable a one of its class as could be selected.”[34]

Taranaki Māori had been gamed.

Armed Camp: New Plymouth in 1860 was fully militarized to extend British Masonic Imperialism to Taranaki.

There was plenty of land available to settlers at this time. The Colonial Government held 42 million acres throughout the provinces, including 25,000 in Taranaki.[35] Waitara was regarded as an obstacle to the planned New Plymouth settlement before the Richmond and Atkinson clans left England. As one emigrant manual stated, Waitara was owned by “a handful of idle braggart-natives who are still suffered to play the dog in the manger”.[36]

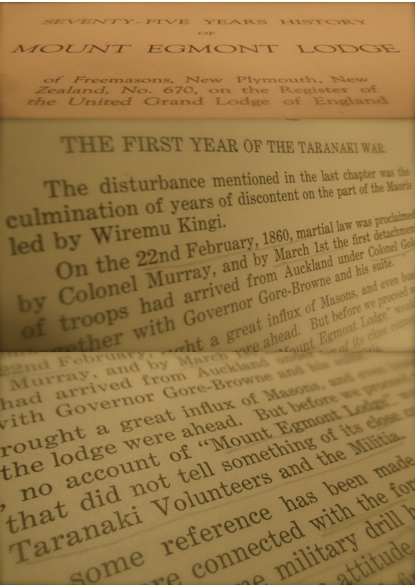

In 1860, numerous Masonic meetings of the Mount Egmont Lodge occurred in a shed belonging to the Taranaki Herald,[37] which was founded by Bro. Garland William Woon who produced the newspaper with the assistance of Bro. W. M. Crompton, as well as Bro. Richard Brown, who had been on the 1858 committee to form a Taranaki militia.[38]

As the war unfolded in Taranaki, the Taranaki Herald thundered:

“The rebels have had the effrontery [the nerve] to make some sort of overture of peace [but] there can be no peace with murderers and assassins. We are at liberty at any time or place to do our best to extirpate [destroy] them as we should any other animals of wild and ferocious nature. Their lives and lands are forfeit and we devoutly hope that no mistaken leniency will allow these natives escaping at least the latter penalty.” [39]

In his 1928 history of the New Plymouth Freemason settlers’ Mount Egmont Lodge of Freemasons 1853-1928, Brother P. J. H. White enthused:

“Tribal wars, land disputes, the coming and going of military men, made New Plymouth for the time being full of bustle and excitement.” [40]

Nearly all of Mount Egmont Lodge’s members were engaged in the First Taranaki War (1860-1861) and the lodge hosted numerous visiting Freemasons from the Imperial and Colonial regiments.[41] It was usual for the lodge meetings to take place in a room in the Masonic Hotel, but because all rooms were probably taken up for accommodation, the ‘Mount Egmont Lodge’ frequently convened in the Taranaki Herald’s shed. Among the visiting Freemasons were, Major Bro. Charles Herbert, who commanded the New Zealand Volunteers and Militia forces.

During the First Taranaki War, the Egmont Lodge was also visited by Bro. Edmund Jacob Whitbread of the 65th Regiment, and Bro. Frederick Bailie who served under Colonel Gold, and both were promoted from Lieutenant to Captain during the First Taranaki War. The Egmont Lodge also hosted Bro. Lieutenant Urquhart, who headed a detachment of the 65th Regiment at the Battle of Waireka, Taranaki, and was accompanied by Bro. Lieutenant Whitbread, Bro. Lieutenant Blake and Bro. Surgeon White of the H.M.S. Niger.

Among the membership of the Egmont Lodge were military officers including Sergeant Bro. George Collins of the 65th Regiment, who joined the lodge in 1860 and served in New Zealand from 1861 to 1865. A company commander of the 65th Captain Bro. T.G. Strange, was mortally wounded at Te Arei pa, which was situated on a hilltop above the Waitara River, on February 10 1861. Captain Bro. T.G. Strange was initiated into the Order in August 1858, at the Pacific Lodge in Wellington, when the owner of the Wellington Independent newspaper, Bro. Thomas Wilmor McKenzie, was Worshipful Master of the Lodge.

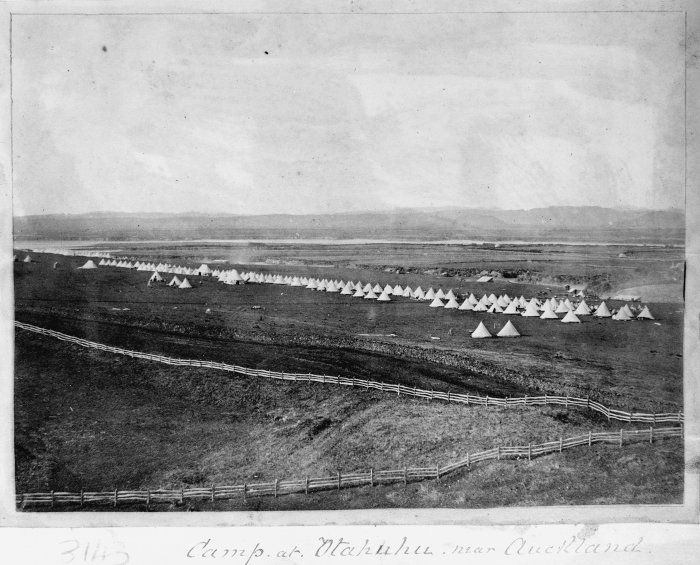

As the First Taranaki War progressed through 1860, the Colonial Government leased 400 acres for a military camp on the land-swindling Reverend James Hamlin’s property at Ōtāhuhu, which was one of four settlements created by Bro. Governor George Grey in 1847-1848 as garrisons. These ramparts located at Onehunga, Ōtāhuhu, Panmure, and Howick were ostensibly built to protect settlers from Māori incursions. They were ‘settled’ by ‘Fencible Settlers’ who immigrated on the condition that the men would fight if needed in return for a cottage within a fenced acre.

In reality, these four settlement towns fulfilled the ‘Settlement’ element of the Discovery Doctrine, a ‘necessary’ stage of colonization. The idea for the Ōtāhuhu Camp was conceived in 1859 and became the military base for the Ōtāhuhu Royal Calvary Volunteers from 1860 to 1864.[42] To further provide for logistics, the Colonial Government leased 100 acres in Penrose for a Commissariat Transport Depot, from the sons of a wealthy Cornwall family, the Maclean’s, in 1860.

The Commissariat Transport Corps was a branch of the British Treasury, meaning that military servicemen were working under a civilian command structure. Since the Commissariat Transport Corps were in charge of all non-military supplies, and coordinated land and inland water transport, and administered the Military Chest from which funds could be drawn for military campaigns — the British Government and the Colonial Government had committed to conquest with this chess move. The Commissariat and the Military Train also had the responsibility for building the military road to link Auckland with the Waikato.

Following the outbreak of the First Taranaki War in March 1860, Colonel Bro. Marmaduke George Nixon, who was born in Malta and trained at Sandhurst Military College, was recalled from retirement. He was made Commanding Officer of two units of the Mounted Defense Calvary (later renamed the Royal Volunteer Calvary), that formed a line of defence across the Waitemata-Manukau isthmus, linking the Fencible settlements of Howick, Panmure, Ōtāhuhu and Onehunga. Bro. Nixon was also called upon to form a Colonial Defence Force when Bro. Governor Grey’s war plans for the tribes of the Waikato south of Auckland emerged.

Ōtāhuhu Camp of Imperial forces: Tents of the 70th, 14th, 40th and 12th regiments. Colonial forces and militia, under the command of Bro. Colonel Marmaduke Nixon, were also raised at the camp.

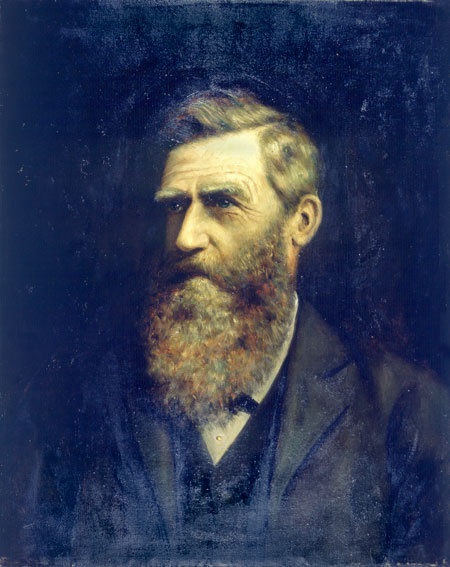

Forebodingly for Māori, the militarist Freemason, Sir George Grey, who was awarded a Knight Commander in the Companion Order of the Bath by Queen Victoria in 1848, was recalled to New Zealand for a second term of governorship on 3 June 1861. Bro. George Grey, who was initiated into Freemasonry in Ireland at the Military Lodge No.83, I.C., was of noble heritage, his cousin was the Earl of Stamford, whose ancestor had fought on the Parliamentary side of the English Civil War against the Royalists. The town of Auckland turned on the pomp for Bro. Grey’s return on 26 September 1861, with a crowd of 8,000, complete with bugles, riflemen and an official welcome – at the 13-acre Albert Barracks site on Fort Street.[43]

The Southern Cross newspaper, owned by land-swindler merchant John Logan Campbell, voiced fighting talk:

“Sir George arrives among us in September 1861, more powerful than any Governor that ever arrived in New Zealand. He has an army at his back, and colonists who have pledged themselves through their representatives to spare neither blood nor treasure in upholding her Majesty’s sovereignty.” [44]

In his 1996 book, The Rich: A New Zealand History, Stevan Eldred-Grigg observed that The Southern Cross newspaper called for a ‘fire and sword’ policy to wrest ‘millions of useless acres’ from the Waikato tribes.

To continue to wage these land wars, the New Zealand Colonial Government needed money. It could have printed its own money debt free, like the colonies of America did more than a century before. But, the printing of Colonial Scrip currencies had been regarded as a rebellion in the American colonies and was one key reason for the American Revolutionary War against Britain, in addition to objecting to Royal Charters to form corporations.[45] Clearly, the New Zealand Civil Oligarchy of rich white men running the Colonial Government knew not to provoke the ire of the British Empire.

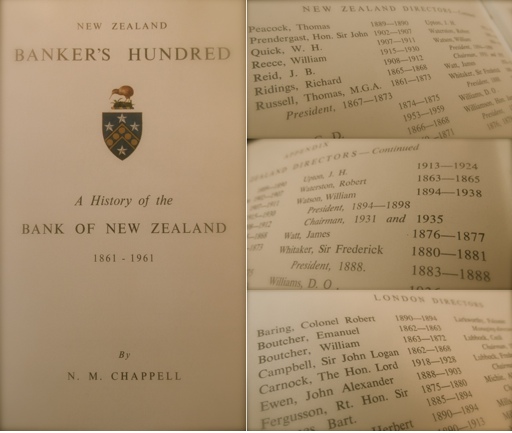

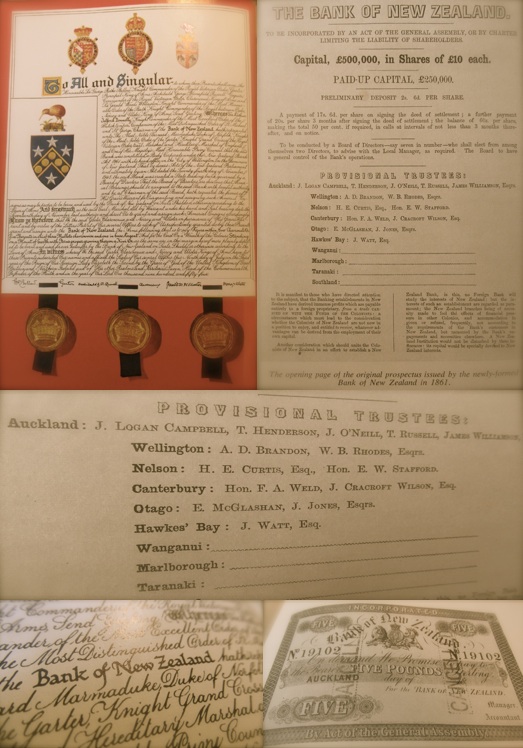

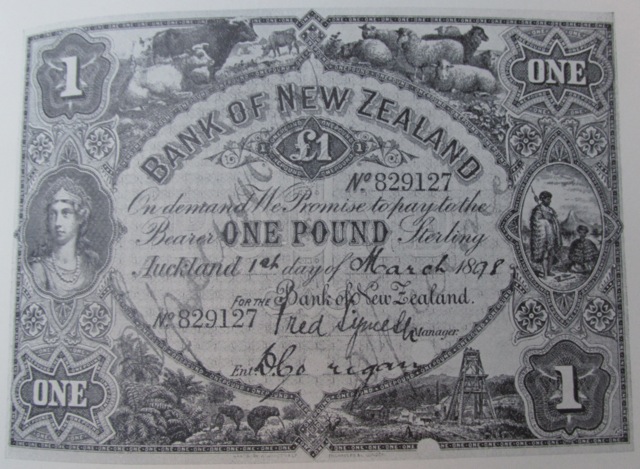

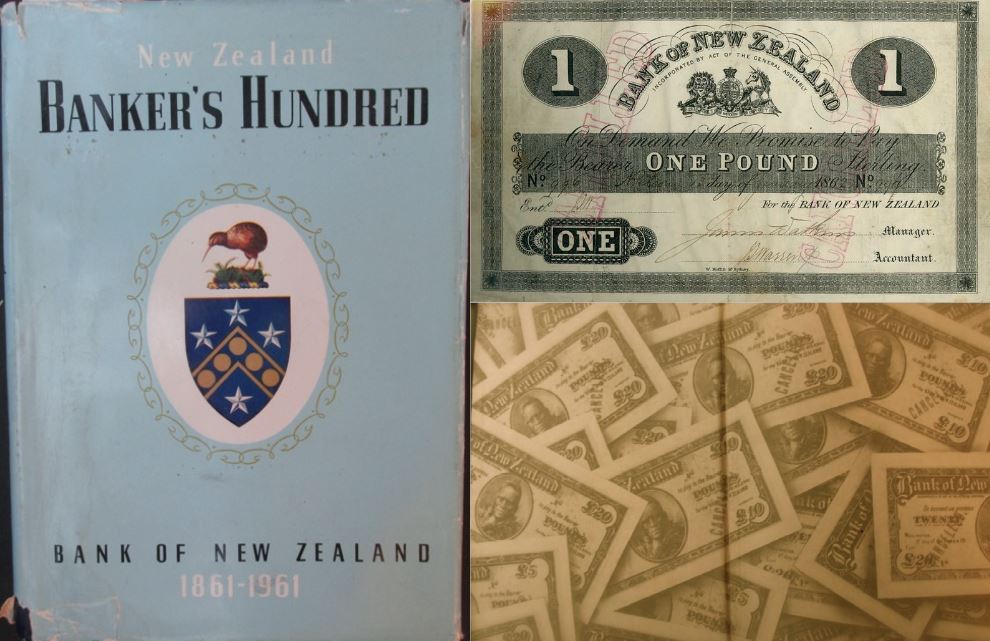

Three weeks after Grey’s homecoming, an ambitious new bank, with initial capital of £500,000, cashed in on colonial parochialism by calling itself the Bank of New Zealand. The BNZ, which was established by legislation and Royal Charter in 1861, and whose solicitors were Freemason Frederick Whitaker and Methodist lay preacher Thomas Russell, became the colonial government’s banker, brokering loans and supplying an overdraft to prosecute British Empire’s war to destroy the resilient communal economy of ‘rebel savage Maoris’.[46]

Indeed, the Bank of New Zealand had the edge over older rivals because of the influence of well-connected players as is evident in the roll of the bank’s original directors, investors and trustees. Included in bank founder Thomas Russell’s ‘Limited Circle’ were:[47] Governor George Grey; three-times Premier Edward W. Stafford of Nelson; [48] Wellington based land swindler William Barnard Rhodes; the bank’s first president; James Williamson, who conducted profitable business for the military commissariat department; and the ubiquitous Sir John Logan Campbell, who was on numerous company boards in the orbit of Thomas Russell.[49] Conspicuously, Russell also became the Minister of Colonial Defence, while Bro. Frederick Whitaker became Premiere of New Zealand during the Waikato War of 1863-1864.[50]

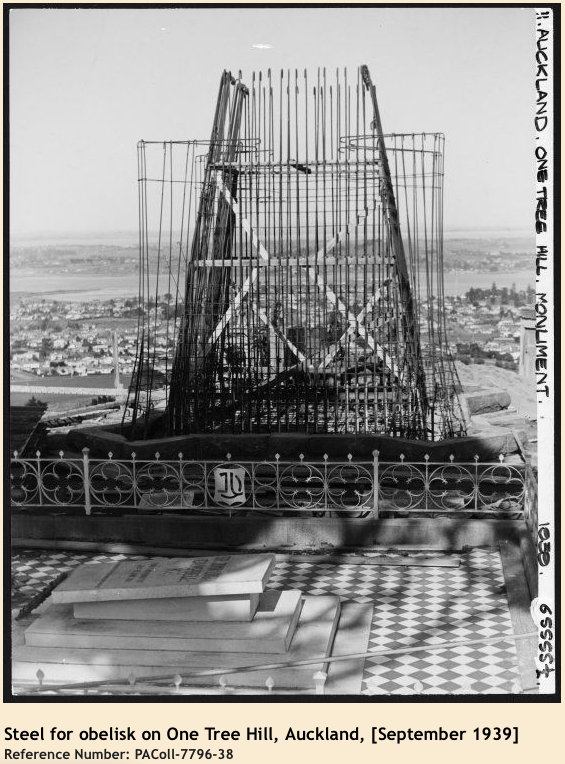

Furthermore, the Masonic influence is evident in the roll of the Bank of New Zealand’s original directors, investors and trustees: Bro. Governor George Grey, Bro. Frederick Whitaker, three-times Premier Bro. Edward W. Stafford of Nelson; Bro. C. J. Taylor, Bro. Thomas Henderson, Bro. William Barnard Rhodes, Bro. A. de Bathe Brandon, and the land-swindling Sir John Logan Campbell, who, while not a Freemason, bequeathed funds for an overbearing Masonic obelisk to be built at the top of Maungakeikei in Cornwall Park, complete with a Māori warrior, as a memorial to the ‘dying’ native race (as many settlers believed this was the fate of the indigenous Māori people).[51]

Not surprisingly, the Bank of New Zealand’s official centennial book, published in 1961, whitewashes the involvement of bank founder Thomas Russell in the conspiracy with his law partner, Bro. Frederick Whitaker, to create a crisis that would force the Colonial Government to borrow heavily. That crisis was a full-scale imperial war against Māori, with Whitaker and Russell at the core of the plot. For one thing, Whitaker – who later became a director from 1880-1888 – had a hand in fomenting the Taranaki Wars of 1860-1863, by misleading the government over their purchase of the land at Waitara.

It is, therefore, a major omission of the bank’s centennial book to mention nothing of its first chief solicitor’s culpability in British Masonic racketeering. In the opening paragraphs of, New Zealand Banker’s Hundred: A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861-1961, author Chappell states:

The Auckland of 1861 was conspicuously a colonial outpost of Empire … Problems and anxieties stood plain, not least a growing threat of conflict with the Maoris. But Lord Palmerston [British Prime Minister 1859-1865], half a world away, had declared that British law should be respected in New Zealand, even if it should take 20,000 men to bring about that result.[52]

Indeed.

At the top of secret Sionist-Rosicrucian English Freemasonry and High Priest of Templar Scottish Rite Freemasonry was 33rd Degree Freemason Lord Bro. Palmerston (born Henry John Temple) who was for most of the time between 1837 and 1865, either the Foreign Secretary, at the British Government’s Foreign Office, or Home Secretary, when he was not wearing the British Prime Minister’s hat. Historian Webster Griffin Tarpley describes Lord Bro. Palmerston as the most powerful leader of the British oligarchy between 1830 and 1865, while historian Nicholas Hagger identifies Lord Bro. Palmerston as the Grand Patriarch of the Illuminati and ruler of all secret societies in the world, including the Grand Master of British Brotherhood during this period.

Although numerous ‘Famous Freemason’ biographical lists and accounts cite Thomas Dundas, 2nd Earl of Zetland, as the Grand Master of English Freemasons from 1844 to 1870, George Dillon stated in his 1885 book, Grand Orient Freemasonry Unmasked as the Secret Power Behind Communism, that hidden masters of the Brotherhood were served by skilled secret plotters scattered amongst the rank and file.[53] According to Tarpley, Bro. Palmerston was the leading imperialist of his time, who was hell bent on forging a world empire.

Indeed, as Tarpley has retold, the British Prime Minister held an outrageously belligerent attitude to any native or colonist people who opposed the British Empire’s brotherhood. Lord Palmerston “thundered” in the British Parliament that wherever a British subject travels the British fleet will resolve his disputes.[54] In his epic study – Treason in America: From Aaron Burr to Averell Harriman, historian Anthony Chaitkin found that a secret network of British-Swiss-Dutch-Venetian plotters used Lord Palmerston’s family estate, Broadlands, as the headquarters for the British Masonic Empire’s ‘black operations’ to subvert rival powers, competing coalitions and indigenous peoples. Furthermore, Queen Victoria was the Patronness of English Freemasonry and her husband George was a Freemason.[55] Because the key oath of Freemasonry is one that obligates the fraternity to always follow orders from above, the merger of Freemasonry with the political-economic-cultural power bases of the British Empire meant obedience to a horrific imperial vision: universal empire.[56]

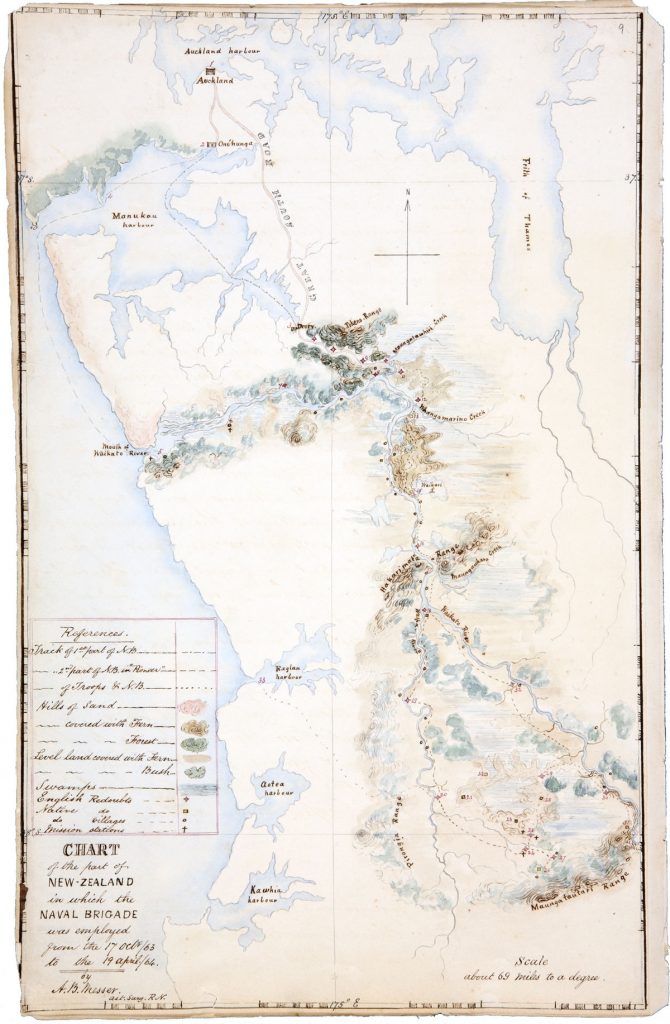

In such a bellicose atmosphere, by Christmas 1861 and at a time when Governor Bro. Grey was faking peace, he had almost 2,500 soldiers that included Freemasons building a military road, lined with telegraph poles and copper wiring that would cut deep into Waikato territory.[57] These Imperial and Militia soldiers were absorbed in the Commissariat Transport Corps for the task of constructing the Great South Road to Mangatawhiri Stream. Among the troops in the Commissariat Transport Corps was 3rd Waikato Militia Captain Bro. James McPherson, formerly of the 93rd and 70th Regiments, who later settled in Hamilton and became the first member of parliament for the district, just one example of how the Masonic Brotherhood capitalized on its engineered crisis.

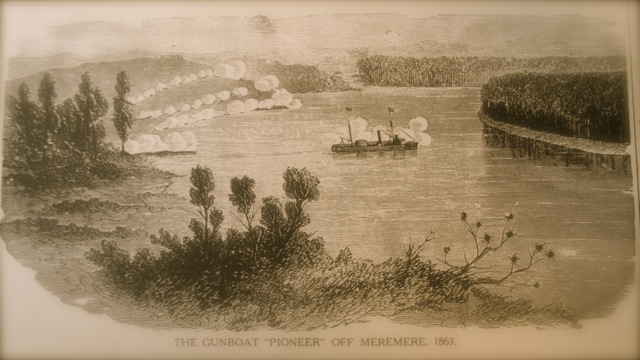

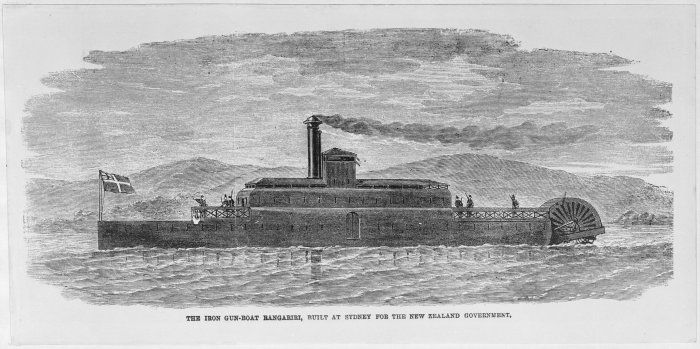

In 1862, Brother Grey bought two steamers for conversion into gunboats to finish charting the Waikato River, charts that Bro. George Grey had started years earlier before he left New Zealand to oversee military operations in the Cape Colony. (During his first Governorship, George Grey was stopped by Tainui chiefs on the banks of the Waikato River at the convergence of the Waipa River, where he was reprimanded for being in Tainui territory, and with no authority to be surveying, and he was told to turn around and to never return). By Christmas 1862, General Cameron had 10,000 Imperial Troops under his command, a fact that ‘the Waikatos’ could hardly miss.[58]

Pioneer at Meremere: One of Governor Bro. George Grey’s ironclad steamers depicted under fire on the Waikato River in 1863.

The gangster-in-suits duo Bro. Whitaker and Methodist lay preacher Russell did not stop with the Bank of New Zealand Act, either. Together, they were key protagonists in the Natives Lands Act of 1862, which ended the Crown’s land-swindling monopoly on land purchases with Māori dating back to the fraud-ridden, rat-eaten Te Tiriti o Waitangi,[59] which had been left to languish in the basement of Government House in Auckland. Then, in 1863, Premiere Bro. Whitaker and preacher-banker-solicitor-insurer and Minister of Colonial Defence Thomas Russell were to drive the ‘wedge of war’ deeper with three more parliamentary acts. The first was the Suppression of Rebellion Act of 1863, which for all intents and purposes upheld the fraud of Te Titiri o Waitangi of 6 February 1840, since the Māori version is the one that counts.[60]

The second piece of legislation that Masonic Bro. Whitaker and Methodist lay-preacher Russell schemed was the New Zealand Settlement Act, which legalized the establishment of military towns on land belonging to Māori that the Masonic fraternity’s Governor could construe were in rebellion against the Crown. And finally, the New Zealand Loan Act, that authorized ‘borrowing’ three million pounds of engraved, land confiscation-backed bonds for a mass grave-consigning conflict that was named, in the grand tradition of the British Masonic Empire, after those they gamed and blamed: ‘The Maori Wars’.[61]

In March 1863, Governor Bro. Grey travelled to New Plymouth to investigate the Waitara Block purchase and he found in favour of Chief Wiremu Kingi and Atiawa iwi. But instead of immediately publicizing his finding that the Waitara Purchase had been illegal and ordering the return of this port and cultivation landblock, Bro. Grey made a move to help cast a wedge for the Second Taranaki War. Bro. Grey ordered the military to occupy Tataraimaka block, the southernmost New Plymouth settler’s farmed land that Māori had occupied since the truce of 1861. Atiawa iwi had made it clear when they occupied the Tataraimaka block that they would only give it up when Waitara was returned to them.

The 57th Regiment moved in without a shot being fired and built Fort St. George on a bluff overlooking the coast. Māori viewed these provocations as declarations of war and on 3 May 1863 ambushed a party of the 57th, killing two officers and six foot soldiers. The two companies of Rifle Volunteers and Militia were re-formed into three, each with bush-ranging units that would make use of new breech-loading Terry carbine rifles, 5-shot revolvers and locally manufactured bush knives.

Between these developments, on April 13 1863, Lord Bro. Palmerston appointed Freemason Bro. George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 3rd Earl de Grey, as Secretary of War. With the 18thRoyal Irish Regiment already en route to New Zealand in early-to-mid-1863, the Commander-in-Chief of British Armed Forces, HRH Prince George William Frederick Charles, the 2nd Duke of Cambridge, who like Bro. George Grey held a title in the Order of the Bath, signed orders for the 43rd, the 50th and 68th Regiments to travel to the far-flung colony. (Prince George was a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath [1855]).[64]

Meanwhile, when Thomas Russell became the Minister of Colonial Defence in 1863, Parliament was like an executive branch of the Bank of New Zealand, 28 shareholders and five directors were there with the founder. On 23 June, Governor Bro. George Grey issued a proclamation for the citizens of Auckland to form a militia. On July 9 1863, Governor Bro. Grey sent out a proclamation ordering Māori in the Auckland Province who lived north of the Mangatawhiri River to take an oath of obedience to Queen Victoria, or cross the river to live in the Waikato. Such an oath was not unlike the submission of a Freemason to always follow orders from above.[65] In effect, Bro. Grey had issued an ultimatum to a people beyond his jurisdiction to order around with a 48-hour eviction notice that did not reach Māori in time.

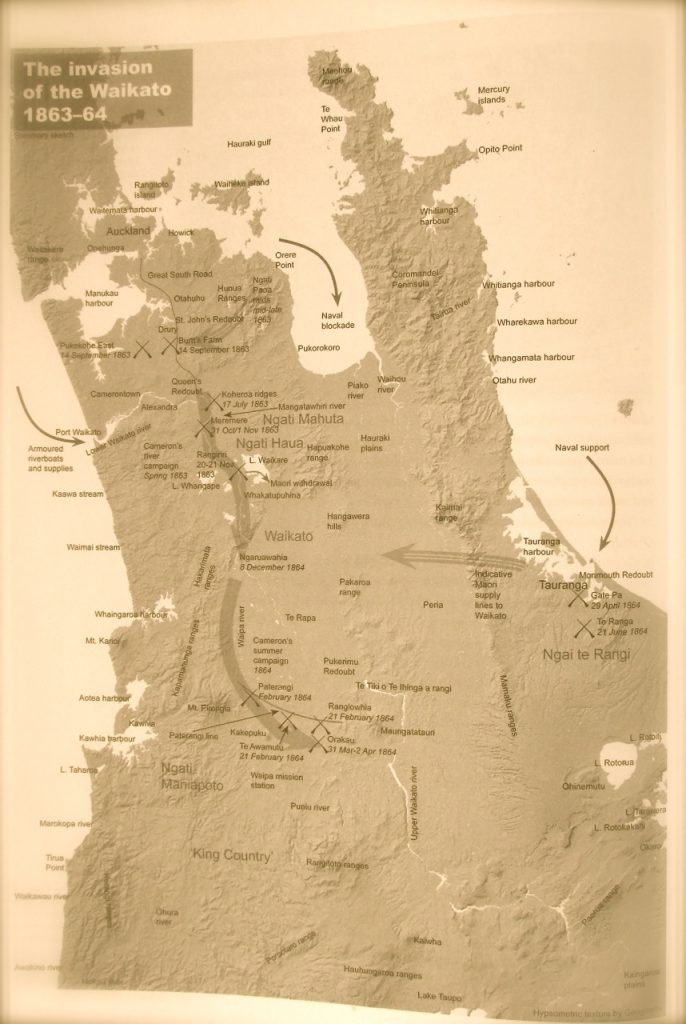

Governor Bro. Grey, who was regarded by historian J.B. Condliffe as “the greatest imperialist of the Nineteenth Century”,[66] had prepared thoroughly for war, as had his General Duncan Alexander Cameron, who would later be made Governor of the Sandhurst Royal Military College. At their disposal were iron-reinforced gunboats for river navigation, including the HMS Pioneer, Rangiriri, Avon, Harrier, Esk, Curacao and Gymnotus. Other ships transporting troops, supplies and weapons were: HMS Pelorus, Eclipse, Miranda, Victoria, Iris, and Cordelia.[67]

Later, the HMS Falcon, and steamers called the Corio and the Sandfly would transport troops for war at Tauranga, while a seventeen gun corvette, the Fawn, and a gun-schooner, the Caroline, patrolled the Hauraki Gulf, to defend Auckland.[68] Also at his and Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron’s disposal were 15,000 men, including 12,000 British army personnel. Lacking a professional Warrior class and the capacity to produce an economic surplus in the league of the British Masonic Empire, the Tainui people of the Waikato, and their allies, had 3,000 to draw on in a shift system, meaning there were only 2,000 engaged in warfare at their maximum strength.

Rangiriri on the Waikato River: One of several ironclad steam-powered gunboats commissioned by Governor Bro. George Grey.

At dawn July 12 1863, General Duncan Cameron, formerly Commander-in-Chief of Scotland, crossed the Mangatawhiri Stream with 700 soldiers into Tainui Waikato territory on the orders of Bro. Sir Governor Grey, an early investor in the Bank of New Zealand. With this act of war, the imperial forces, in effect, ‘Crossed the Rubicon’,[69] or ventured beyond the point of no return into territory beyond his jurisdiction to provoke the Waikato War.[70] On 13 July, 300 soldiers of the 65th Regiment crossed the Waikato River at Tuakau to establish the Alexander Redoubt on the high cliffs above the river.

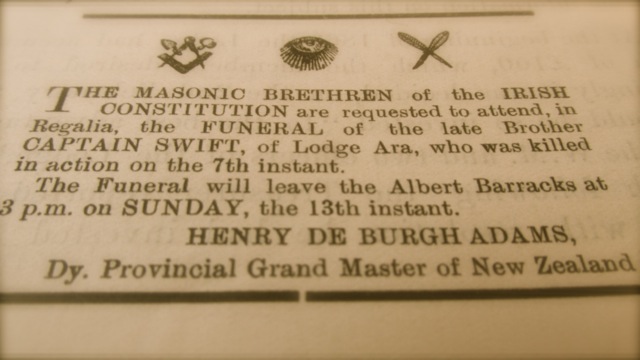

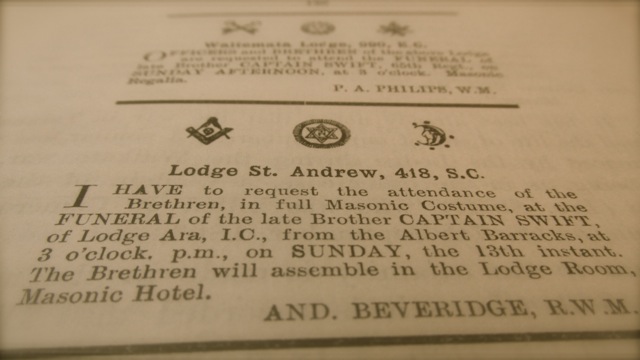

The fusion between three institutions of the British Empire – Freemasonry, the British Army and the Church of England – is evident in a funeral to honour to a fallen Brethren at an early stage in the Waikato campaign.

On September 7 1863, a Freemason Captain Bro. Swift of the 65th Regiment was killed during a rescue operation of ‘friendly Maoris’ engaged at Camerontown, near Tuakau on the lower Waikato River. Bro. Swift was shot through a lung and on one side while leading an ill-conceived bayonet charge against ‘rebel Maoris’ camped in the bush who were thought to be drunk on rum. Upon Bro. Swift giving the order to charge, the first volley of shots fired by ‘the natives’ cut Captain Swift down, and he died about 7.30 that evening, as John Featon retold in his account, The Waikato War. A funeral for Bro. Swift was advertised by Irish, English and Scottish Constitution lodges, requesting Brethren of the Brotherhood to meet in full Masonic Regalia at the Albert Barracks in Auckland on 13 September 1863. Bro. Swift’s burial, which was noticed by James Bodell, author of A Soldier’s View of Empire, took place at the Church of England cemetery, with military honours. (The foundation stone of the original St Paul’s Church was laid in a ceremony by Masonic brethren).

Fusion of Freemasonry and Imperialism: The funeral procession for Captain Bro. Swift of the Imperial 65th Regiment convened at the 13 acre Albert Barracks on September 13 1863.

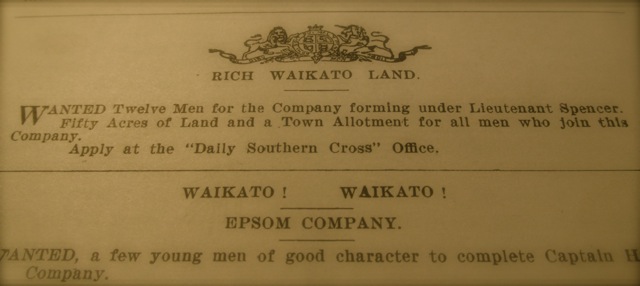

The day after Captain Bro. Swift’s funeral, a ship called the Star of India arrived in Auckland with 407 officers and foot soldiers selected under Colonel Pitt’s supervision in Melbourne. This detachment of Military Settler volunteers were drafted into the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Waikato Militia Forces. Many of the men that fought in these Waikato Militia were Freemasons. Like the men of Taranaki, the Waikato Militiamen were enticed with the offer of one town acre and farmland, the size of which reflected the British class system in the military. Thus, a field officer would receive 400 acres, a captain was promised 300, a surgeon 250, a sergeant 80, a corporal 60 and a private 50.

It is not without irony, that many of the privates who fought in the Imperial and Colonial Army and Volunteer Militias in the New Zealand Wars “were working people who lost their livelihoods through economic recession, famine or dispossession of land”, as historian James Belich noted. In others words, through emigration and warfare the British Oligarchy were exporting crises of their own making to the far-flung reaches of the British Masonic Empire, to control more territory as a means accumulate economic wealth faster than rival powers.

Militia Enticement: This ad stated that the Daily Southern Cross newspaper premises would have a double life as a recruitment office for raising a Waikato Militia.

After dispatching the pa at Meremere, Cameron advanced 13 miles with an attack force of 1300 men to Rangiriri, a battle in which warriors signalled a truce, with a white flag, and 180 warriors were taken as prisoners on the pretext that they had surrendered.[71] General Cameron was later awarded a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath for this encounter.

During the Waikato campaign, Military Surveyor Bro. Major Charles Heaphy guided the imperial and colonial forces.[72] With a surveyor on hand, General Cameron showed an acumen for the Doctrine of Discovery’s elements of ‘Conquest’, ‘Actual Occupation and Current Possession’, and ‘Civilization’, by accurately marking out where his forces were occupying land as the places that would become the military settlements once the lands were officially confiscated.

These garrison towns were at Karapiro (Cambridge), Kirikiriroa (Hamilton), Alexandra, Te Awamutu, Kihikihi, Ohaupo, Pirongia and Ngaruawahia. The 1stWaikato militia were based in Tauranga, the 2nd Waikato around Te Awamutu, Pirongia and Camp Alexandra (where the Freemason Beta-Waikato Lodge was located), the 3rd Waikato Volunteer Corp at Cambridge (or Karapiro, where the Freemason Alpha-Waikato Lodge was located), and the 4th Waikato at Kirikiriroa (or Hamilton).[73]

The New Zealand Herald‘s belligerent founder, Freemason Bro. William Wilson got an early headline he was after.

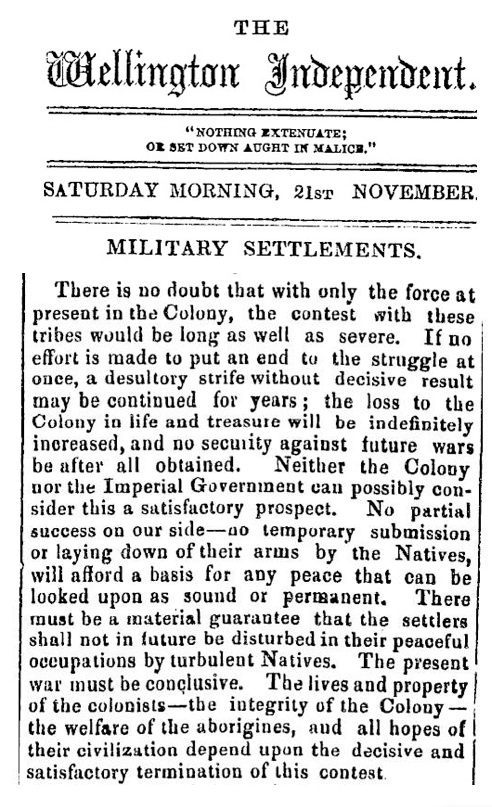

The Wellington Independent, which was owned by Freemason Bro. Thomas Wilmor McKenzie, printed a propagandist “memorandum” that was written by Colonial Government Ministers on 21 July 1863 to the Governor and forwarded by Bro. Grey to the British Secretary of State. The memorandum, which was printed on 21 November 1863, evidently opened with the fiction that the Waikato tribes were resolved to drive out or destroy the colonists of the North Island. The Wellington Independent quoted the memorandum:

“There is no doubt that with only the force at present in the Colony, the contest with these tribes would be long as well as severe. If no effort is made to put an end to the struggle at once, a desultory strife without decisive result may be continued for years; the loss to the Colony in life and treasure will be indefinitely increased, and no security against future wars be after all obtained. Neither the Colony nor the Imperial Government can possibly consider this a satisfactory prospect. No partial success on our side – no temporary submission of laying down of their arms by the Natives, will afford a basis for any peace that can be looked upon as sound or permanent. There must be a material guarantee that the settlers shall not in future be disturbed in their peaceful occupations by turbulent Natives. The present war must be conclusive. The lives and property of the colonists – the integrity of the Colony –the welfare of the aborigines, and all hopes of their civilization depend upon the decisive and satisfactory termination of this contest.”[74]

The memorandum finished forebodingly, stating that the Colonial Government had resolved to confiscate the lands of any tribe, now or in the future, who were found to be in defiance of the Queen’s supremacy.

But, the drive to transform the Waikato region from what was, in essence, an independent Māori state into a Masonic province resulted in the loss of a popular Freemason Colonial – Bro. Marmaduke George Nixon – who had been responsible for forging the Colonial Defence Force at the garrison settlements of Howick, Panmure, Ōtāhuhu and Onehunga, and the Royal Volunteer Calvary at the Ōtāhuhu Military Camp.

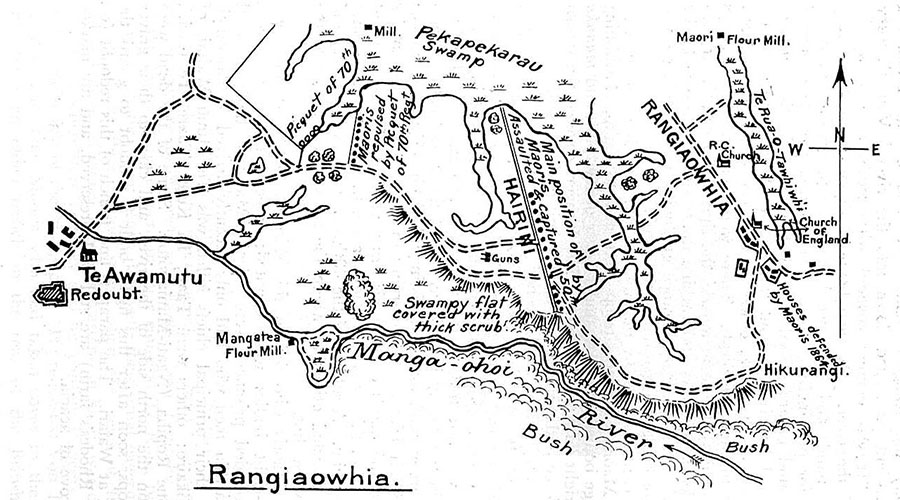

In the Battle for Rangiaowhia, three miles east of what would become the Waikato military garrison settlement of Te Awamutu – Bro. Marmaduke George Nixon was mortally wounded – and his death three months later inspired the construction of the first Masonic monument of the New Zealand Wars at Ōtāhuhu. On the night of 20th February 1864, and under the command of Captain Von Tempksy – an almost 1000-strong advance guard consisting of the No. 2 Company of the Forest Rangers, Colonel Bro. Nixon’s Colonial Defence Force Cavalry corps and Mounted Artillery, moved with detachments of the 50th, 65th and 70th Regiments, and a rearguard of No. 1 Company of Forest Rangers – that passed dangerously within a mile of Paterangi pa, under strict orders of silence. Swords, bridle chains and the horses’ hooves were wrapped in cloth and moved through the fern ridges to Te Awamutu with the benefit of local knowledge of two Māori-Pākehā, James Edwards (Himi Manuao) and John Gage, and pressed onto Rangiaowhia, an unfortified food basket village with a flour mill, grain fields, vegetable gardens and orchard, that was occupied by Ngāti Āpakura and Ngāti Hinetū. In attacking Rangiaowhia on 21 February, General Cameron’s objective was to outflank the Kingite’s defences, draw Māori toa (or warriors) from the Paterangi pa, by the Waipa River, into a direct and overwhelming battle with the Colonial and Imperial Forces to destroy the Kingite army, as historian James Belich found.

The idea was that a supplementary column, led by General Cameron, would transport the artillery and supplies following the risky penetration of the Paterangi Line, which was system of pa in the vicinity of Paterangi, deep in Waikato territory. While many surrendered in the Roman Catholic Church at Rangiaowhia, some held out to defend their village, such as from St Paul’s Anglican Church, where shots were fired through the windows, as historian James Cowan recorded.

About 10 or a dozen warriors fired from a large raupo-walled whare, which either caught fire in the volleys or was set alight, and all were killed by gunshot or the fire, including chiefs Ihaia and Hoani. Three corporals were shot dead, and Colonel Bro. Marmaduke Nixon was shot through the left lung, and he died of gangrene on 27th May. Colonel Bro. Marmaduke Nixon was honoured with a full Masonic military funeral on 30 May 1964, the “largest ever known” procession traveled from the Albert Barracks to the Symonds Street cemetery.

Having provoked the 2nd Taranaki War, and ordering General Cameron to invade the Waikato, Governor Bro. Grey and General Cameron made war in the Bay of Plenty. Vast swathes of land were confiscated in Māori territories where the Masonic Colonial and Imperial forces made war. In all,  1.3 million confiscated hectares became Masonic territories, and were used as collateral for loans raised to wage war during this period.[75] On the fraternally symbolic date of 13 May 1864, the Bank of New Zealand opened an agency in the garrison town of Ngaruawahia, the base of the Kingitanga, that had been insultingly renamed Newcastle. This extension of the bank’s “operations to Ngaruawahia, the northern gateway to the rich and promising Waikato basin” symbolized another franchise of the bank start-up. Here, at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipa rivers, the Bank of New Zealand’s investors were signaling they were capitalizing on the ‘primitive accumulation’ afforded by their fundraising for the Waikato War to enable a new Masonic Territory.[76]

1.3 million confiscated hectares became Masonic territories, and were used as collateral for loans raised to wage war during this period.[75] On the fraternally symbolic date of 13 May 1864, the Bank of New Zealand opened an agency in the garrison town of Ngaruawahia, the base of the Kingitanga, that had been insultingly renamed Newcastle. This extension of the bank’s “operations to Ngaruawahia, the northern gateway to the rich and promising Waikato basin” symbolized another franchise of the bank start-up. Here, at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipa rivers, the Bank of New Zealand’s investors were signaling they were capitalizing on the ‘primitive accumulation’ afforded by their fundraising for the Waikato War to enable a new Masonic Territory.[76]

The smug humour of the Colonial Crony Capitalists, especially those in the inner-circle of the Bank of New Zealand, is cringe-worthy.

A conquest by paper completed what could not be accomplished by gunpowder. The Native Rights Act of 1865, which categorized Māori as the Queen’s natural born subjects, deemed that any cases involving Māori and Māori land were to be settled in the Native Land Court.[77] Colonial government politician Henry Sewell spoke of the Native Land Court’s objectives:

“to bring the great bulk of the lands of the Northern Island which belonged to the Natives … within reach of colonization … [and to cause] the detribalization of the Natives, – to destroy, if it were possible, the principles of communism which ran through the whole of their institutions, upon which their social system was based, and which stood as a barrier in the way of all attempts to amalgamate the Native race into our social and political system.”[78]

Anyone could make a claim against Māori land and because Native Lands Court chief judge Francis Dart Fenton stipulated that such claims had to be proven in a court house, this edict compelled Māori to leave their land, come to town and wait long periods for their case to be heard. Surveyors, land-agents, lawyers, and money-lenders targeted Maori, who often lost land to settle debts foisted upon Māori by such predators.[79]

Māori Rebellion a Fiction of Colonialists

The British Masonic oligarchy, which had an established habit of looting the world, regarded New Zealand as a territory rich in resources to serve their imperial ambitions to supplant other rival powers. Amid tensions over land, racial prejudice and competing British ideas about how to develop a colony inhabited by ‘savages’, matters were bound to turn ugly. For their part, Freemasons in New Zealand were plotting against Māori across multiple fronts.

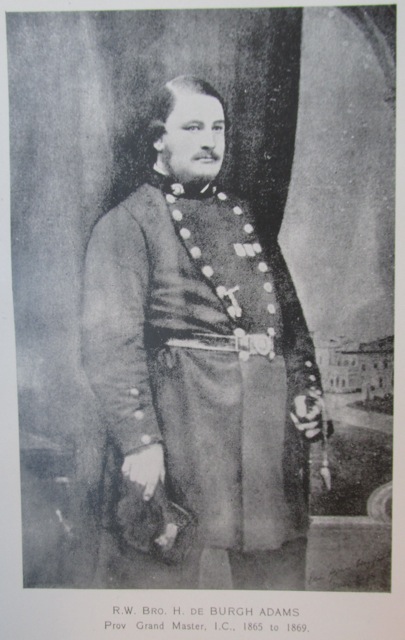

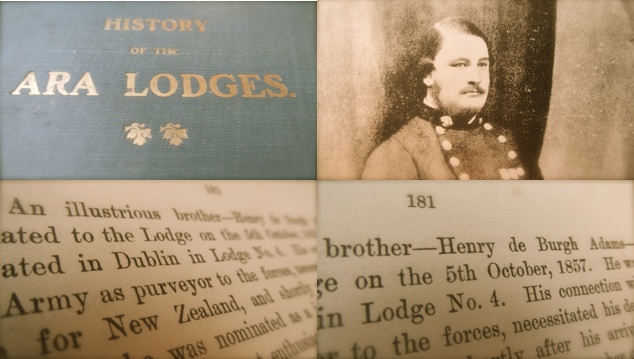

Bro. Major Henry De Burgh Adams, Purveyor to the Armed Forces, founded five strategically located lodges during the NZ Wars, and was Provincial Grand Master of the Irish Constitution Freemasons of New Zealand (1865-1869).

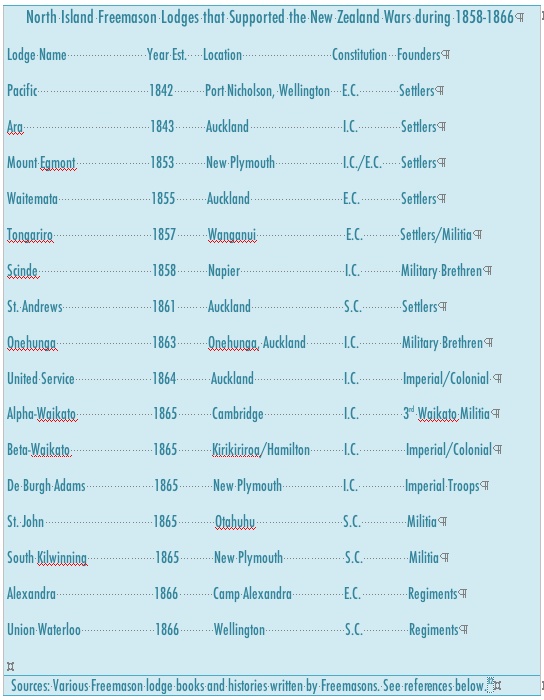

During the crucial 1858-1866 period of the New Zealand Wars, there were 16 Freemason Lodges that had members or hosted visiting brethren who were involved in the fighting, or recruited new Freemasons from the regiments and militias, or who politically and economically supported the conflicts, or were co-conspirators in plots to trigger war. The locations of these lodges, and the years they opened, under various British-centric English, Scottish and Irish, constitutions denoted as E.C., S.C. and I.C., respectively, appear in the following table. Their geographical spread with time show a conscious awareness to advance the ‘great game’ of empire together. For example, the Irish Constitution Scinde Lodge in Hawke’s Bay, established in 1858 in a location where Freemasonry had no lodge, and was founded mostly by militia men and also one of the landed gentry, Bro. Donald McLean, Chief Commissioner for Native Land Purchases, who had accumulated a large estate.

The Hawke’s Bay Brethren were granted a dispensation, or permission, from the Ara Lodge in Auckland, to form the Scinde Lodge. Whereas, Lodge United Service in Auckland was founded in 1864 wholly by Imperial and Colonial Forces during the height of the New Zealand Wars, on the authority of Bro. Major Henry De Burgh Adams, at the time Provincial Grand Master of the Irish Constitution Freemasons of New Zealand.

An energetic Freemason, Major Bro. Henry De Burgh Adams was Purveyor to the Armed Forces. His roll in Freemasonry seemed to mirror his military function as chief of supplies. Bro. De Burgh Adams, who was initiated into the Freemasonry’s Irish Constitution at Dublin’s Lodge No. 4 and came to New Zealand in 1857, opened lodges where they were strategically needed.[80] Bro. De Burgh Adams was a founder of the Onehunga, United Services, Alpha-Waikato, Beta-Waikato Lodges, and he evidently planned two more lodges in the Waikato. Bro. Major Henry De Burgh Adams was behind the founding of the De Burgh Adams Lodge in New Plymouth, a lodge founded in 1865 by Imperial Troops and local Militia Freemasons, who named it after the newly appointed Provincial Grand Master of the Irish Constitution Freemasons of New Zealand.[81] (Twenty-two of the founding members of the De Burgh Adams Lodge were simultaneously Egmont Lodge members).

This Provincial Grand Master position was created to hasten the speed of initiating new men into the Order, establishing new lodges, at a time when communication was slow, and to recognize “the Islands of New Zealand as a Masonic province”.

Freemasons during this 1858-1866 period had either command, key rolls, or a presence in the following regiments: the 12th Regiment, the 40th, the 43rd , the 46th, the 50th, the 57th, the 65th, the 70th, the 93rd, the 18th Royal Irish Regiment, the Royal Artillery, the Royal Engineers, and the Royal Navy’s H.M.S. Niger. Freemasons also filled rank and file positions of several militias: the Taranaki Voluntary Corps, which included the First and Second Company of Taranaki Rifle Volunteers; and Waikato companies, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Waikato Regiments, and other militia forces such as the Forest Rangers.[82] For example, Bro. William Anderson served in militia in 1863-64, having arrived in the Colony at Onehunga the day the corvette H.M.S. Orpheus was wrecked on the Manukau Harbour bar, February 7 1863, where he immediately joined the St. Andrew Lodge. As Masonic historian Bro. Alan B. Bevins wrote in, A History of Freemasonry in North Island New Zealand, “In the time of military engagements, [Freemasons] fought battles by day and attended lodges by night.”

In 1865, during the 2nd Taranaki War General Duncan Cameron, along many of his officers and foot-soldiers, had come to see that New Zealand Wars were a land-grab, albeit rather belatedly. General Cameron fell out with Bro. Grey and quit.[83] There had been growing discontent in London, in both Whitehall and the press, that the war was cruel, immoral and intended to dispossess Māori.[84]

Cui Bono?

In the days of the Roman Empire, a crucial question was asked when plots surfaced: ‘Cui Bono?’ or ‘Who Benefits?‘

As Henry Sewell put the motives of those that ruled the seat of Colonial Government in Auckland during the hostilities,

“The people of Auckland have got effectual hold of the British Army, the British Treasury and the Colonial Chest and they will not let them go till they have settled the native difficulty and made themselves independent proprietors out of the native estate”.[85]

Even as the New Zealand Wars dragged on through to 1872 and beyond, the Colonial Crony Capitalists and the Freemason Brotherhood benefited immensely. The most fertile lands in the Waikato, Taranaki and Bay of Plenty were confiscated, 1,202,172 acres, 1,275,000 and 738,000, respectively. Although some land was returned, 314,262 acres in the Waikato, 256,000 in Taranaki, and 490,000 in the Bay of Plenty, these lands were easy to alienate because they were either under individual title, or Māori were too afraid to assert their rights in the settlements, or tribesmen were swindled or bullied. For instance, in the year that immediately followed hostilities in Taranaki, 557,000 acres were lost this way.[86]

In 1873, Thomas Russell led a syndicate that persuaded the Colonial government to sell 80,000 acres of the Piako swamp, near the Firth of the Thames, 50,000 acres of which became Josiah Clifton Firth’s estate.[87] By 1873, in the Hawke’s Bay where Ngati Kahunugunu had either fought with the settlers or remained neutral, nearly 4 million acres of their best land had been swindled from them by approximately 50 European speculators.[88] Whitaker and Russell also speculated in gold mining, buying out all six shareholders of the Caledonian Mine in the Coromandel prior to it making a ‘world class’ strike.[89]

Founding member of New Zealand’s first Freemason lodge Bro. William Chisholm Wilson, who started The New Zealand Herald to provide a mouthpiece for those colonists that wanted the prosecution of the war to be more vigorous, joined the board of directors of the Bank of New Zealand in 1868 and held his board seat until 1876. Wellington based land swindler Bro. William Barnard Rhodes, and one of the original trustees of the Bank of New Zealand, had accumulated a fortune of £500,000 when he died.

Sir John Logan Campbell left a bequeath for a Masonic obelisk, in ‘respect’ of the ‘dying Maori race’ that he and his fellow Colonial Oligarchy undermined.

Through all of this epic rort, the investors in the Bank of New Zealand received handsome dividends every year right through until 1887, when bank president John Logan Campbell informed shareholders that a dividend would not be paid amid an economic depression. The monetary cost of the war is widely thought to be £3,000,000, which was evidently a “permanent loan”.

This description of a permanent loan is given some weight by historian J.B. Condliffe, who stated in his 1927 edition of A Short History of New Zealand that a part of the public debt, a figure of £2 million, is recorded year on year as ‘Maori War debt’, meaning that “two generations of New Zealand taxpayers have therefore paid interest upon the loans raised in the ‘sixties to pay the expenses of the war.”[90]

In his History of the Bank of New Zealand, author N.M. Chappell brazenly sanitized the credit manufacturer’s dark history when he stated:

“The Government was embarrassed by heavy commitments arising from the Maori Wars and leaned heavily on the Bank of New Zealand for assistance.”[62]

The Bank of New Zealand – which was established by Royal Charter and Colonial Government legislation in 1861 – had brokered finance of £3 million from the London and Sydney money markets to escalate the New Zealand Wars, after the Imperial Government’s terms were deemed to onerous and were declined. When the initial war bonds and securities to invest in the ‘Maori War’ did not sell at the London and Sydney bond markets as well as the criminal banking cliqué had wished, the Bank of New Zealand doubled down. At the age of ‘terrible two’, the N.Z. Government’s banker supplied a monthly overdraft at 5 to 7 percent ‘interest’. This credit line varied and peaked $818,000 during the Waikato War.

Surveyor Bro. Charles Heaphy, who emigrated with the New Zealand Company’s Colonel Bro. William Wakefield on the Tory in 1839, was given the post of Commissioner of Native Reserves as a reward of political support to Sir Bro. Donald McLean. The former Chief Land Purchasing Commissioner, Bro. McLean — who had amassed an estate of 50,000 acres in the Hawke’s Bay and part-owned an 80,000 run next to Lake Wakatipu, conspired with Bro. Whitaker, Bro. Isaac Newton Watt and Christopher William Richmond over Waitara — became Minister of Colonial Defence and Native Minister in 1869 to end Te Kooti’s East Coast War. The Colonial Constabulary was McLean’s brainchild. After Grey was recalled from the colony, Bro. McLean was the only man with the standing to galvanize the support, the resources and the men to forge an armed police force to wage guerilla warfare. [91] Bro. Frederick Whitaker became MP for Waikato in 1876, and subsequently the Attorney General twice more, and Premiere once again.[92]

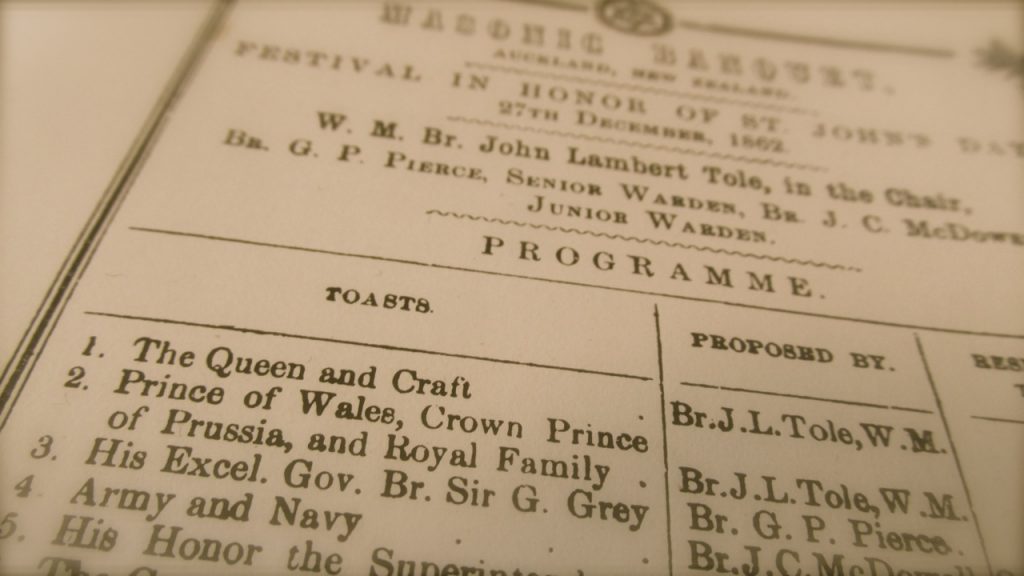

When Bro. George Grey was stood down as Governor in November 1867, the Masonic Brotherhood of Wellington sent Grey a letter of gratitude for his services to the Colony. In addition to Bro. Grey falling out with General Cameron, who had belatedly criticized the wars as blatant land grabs, the Masonic-dominated Auckland Oligarchy scapegoated Bro. Grey over failing to put down the ‘Maori Rebellion’ quickly once the Waikato War commenced. Conspicuously, in The History of the Ara Lodges, the only mentions of Governor George Grey is in a toast list for a St John’s Day Masonic Banquet from 27th December 1862, and on the occasion sending a congratulatory letter in mid-1863 to the Prince of Wales Bro. Albert Edward for his wedding via the Governor. Both mentions were evidently a time when Auckland Freemasons were happy with Bro. Grey’s military preparations.