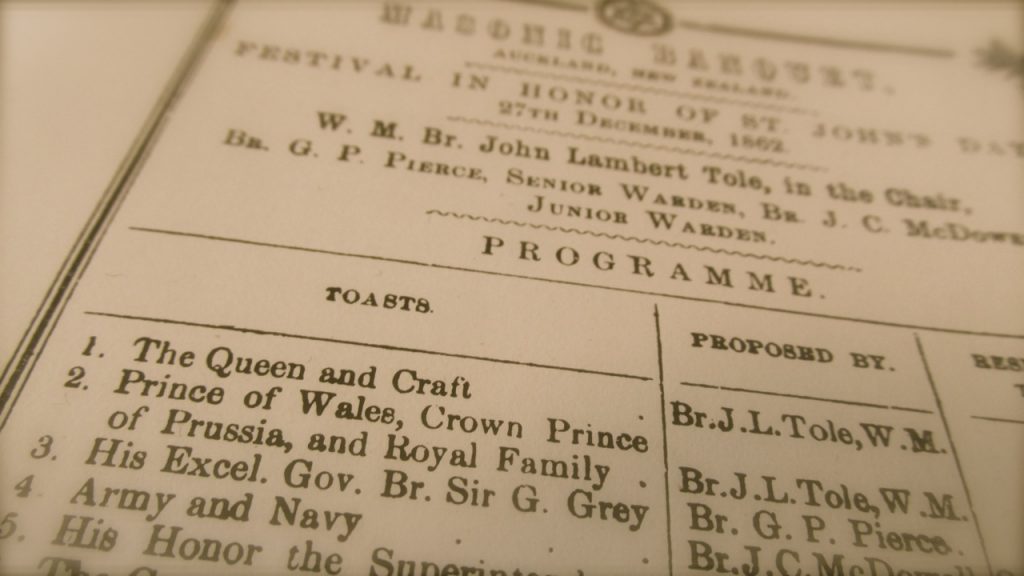

In the Colonial-era, Freemasons controlled the political, commercial and martial power structures of New Zealand. Freemasons appointed their members of the brotherhood to key positions in the New Zealand Colony.

Dispatch from Ihumātao #002

By Snoopman

A Masonic Eviction Notice – 1863

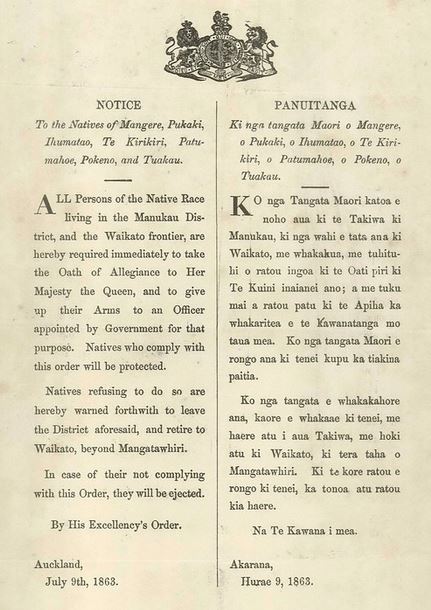

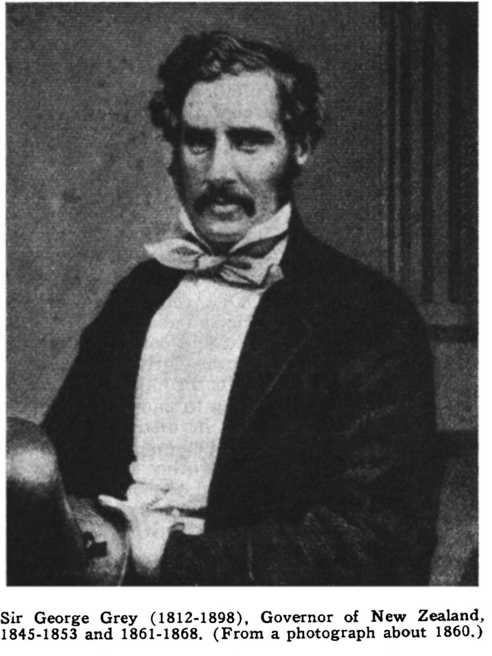

On July 10th 1863, an eviction notice was served on ‘the Natives’ of Ihumātao by the authority of Governor George Grey – a Freemason Brother.

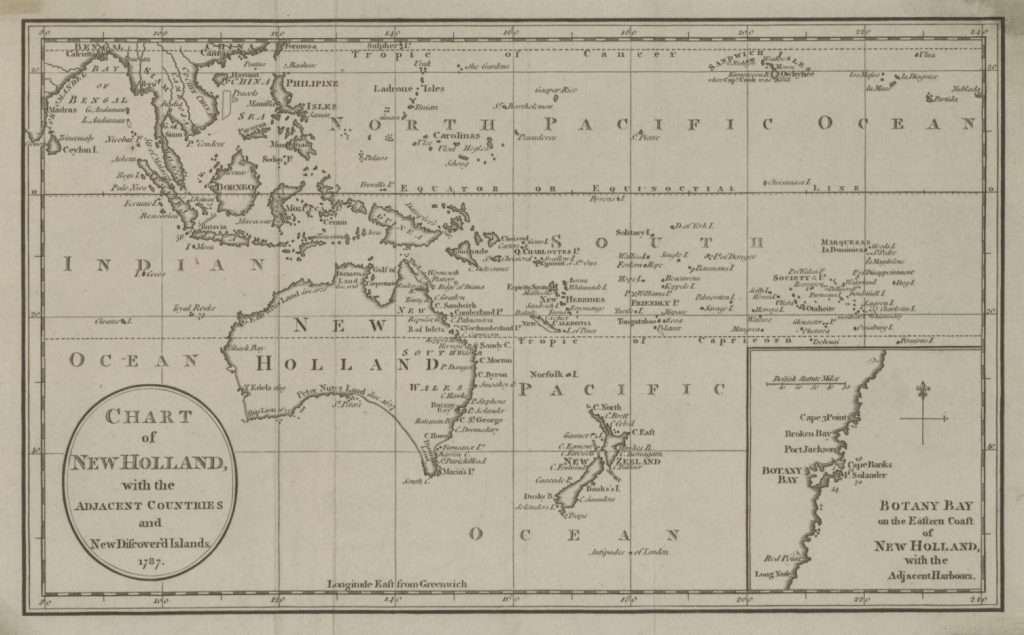

Often referred to as ‘Grey’s Proclamation’, this ultimatum demanded that ‘the Natives’ of Ihumātao – as well as nearby Mangere and Pukaki, and also Te Kirikiri, Patumahoe, Pokeno and Tuakau – submit to the sovereignty, or mana, of Queen Victoria. The proclamation also demanded Māori to hand over their weapons, or they would be force-ably ejected if they did not vacate their lands.1

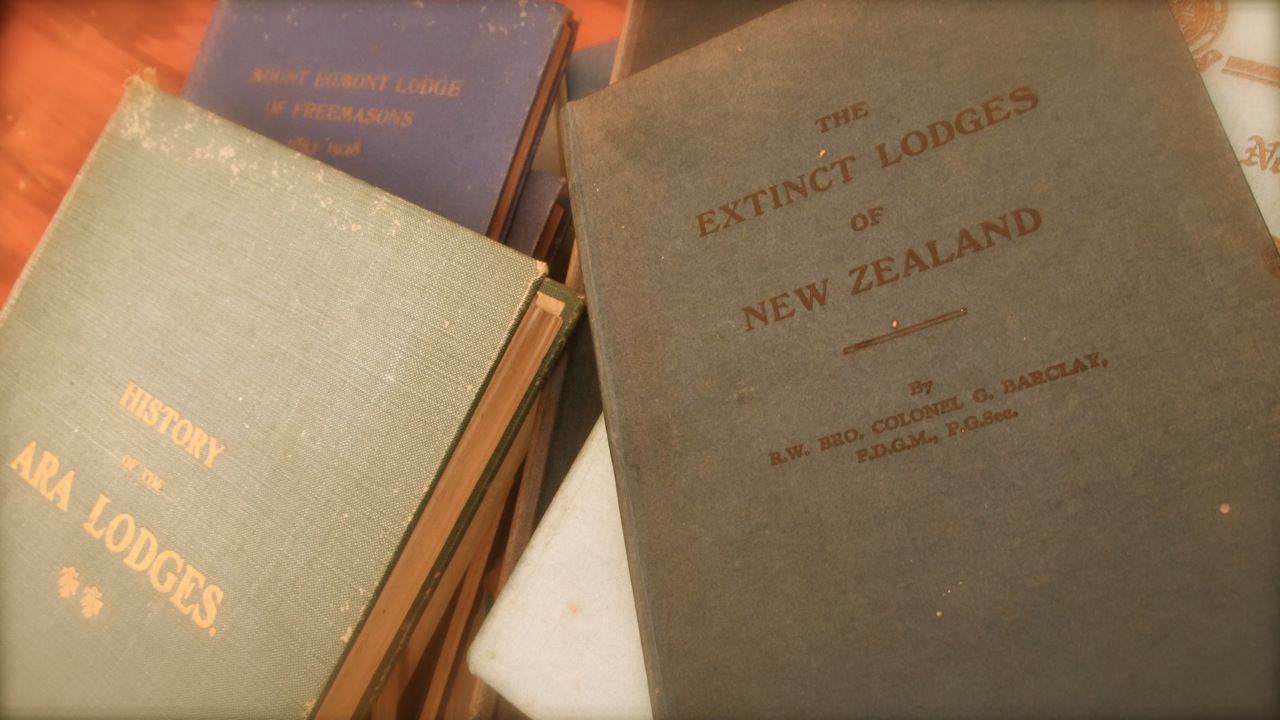

In the Colonial-era, Freemasons controlled the political, commercial and martial power structures of New Zealand. Freemasons appointed their members of the brotherhood to key positions in the New Zealand Colony. Despite the prominence of many of their members in public life, Freemasons were careful to keep the role played by their secret network largely out of history.2

The secrecy worked as a weapon of intelligence, solidarity and plotting to construct Masonic districts and provinces, upend the Māori communal economy and establish substantive sovereignty by gaining large tracts of land through swindle, struggle and stealth.

Parallel History: Suppressed from most public records by Masonic hands, Freemasonry’s structural power as an instrument of imperial expansion was rendered invisible.

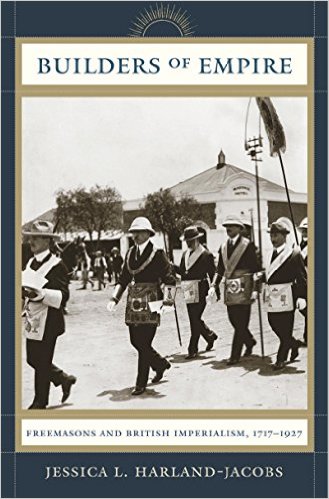

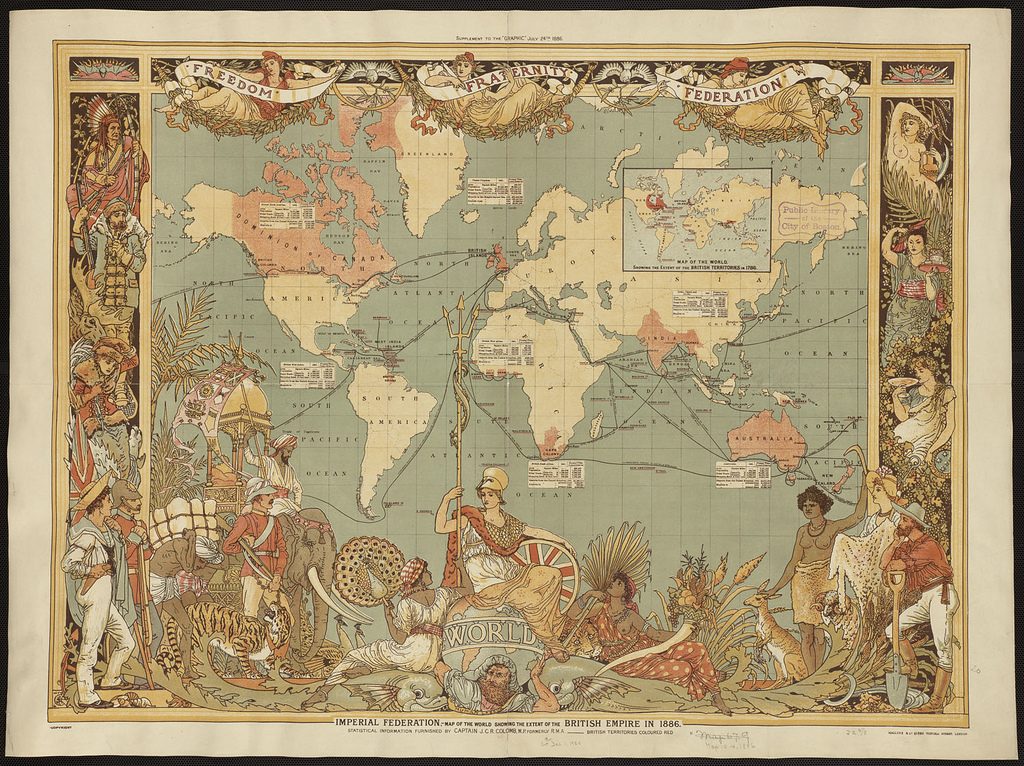

The primary secret mechanism by which the British Empire spread throughout the ‘New World’ was through the secret society of Freemasonry. In turn, Freemasonry was spread mostly through the military regiments, including the navy, as Jessica Harland-Jacobs showed in her book, Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717-1927.3 Harland-Jacobs, who accessed numerous Freemason libraries for her PhD including the Royal Archives, claims that Freemasonry merged with the British Government and the British Monarchy during the 1790s and over a period of three decades re-invented its political leanings and ideology. However, as a study of British Masonic Imperialism, Harland-Jacobs’ work does not reveal the network of the secret brotherhood and their roles in the British Empire. Builders of Empire masks how two British Empires were layered, and why.

There was the Christian British Empire, complete with missionaries exercising ‘soft-power’ to civilize ‘the natives’. And there was the hidden British Masonic Empire hell-bent on world domination, as Nicholas Hagger found in his epic study, The Secret History of the West, that modelled for the patterns of revolutions, how secret societies plotted them and reasons for the subterfuge.4 Their hell-bent vision competed with a rival Brotherhood, French Templar Freemasonry and underpins centuries of warfare, violent state formation and dispossession.

British Freemasonry was Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry, which founded a United Grand Lodge in 1717 to unify English resistance to Jacobite Templar Freemasonry, that formed around the Scottish Stuart dynasty, whom were formally and permanently banished the same year from the British Isles. It was at this point, in 1717, when Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry came to rule over the British Monarchy and the Church of England, after having successfully achieved a political and business merger with the Dutch in 1688. More specifically, the ‘Glorious Revolution of 1688’ – which saw Prince William of Orange and his consort Mary wrest control of the British throne from King James II after they landed at Torbay, near Brixham, Devon, on November 5 with 250 ships – was secretly bankrolled by English Rosicrucian Freemasons, the Bank of Amsterdam, and Amsterdam Jews, and was part of a two-hundred year Venetian project to takeover Britain.

According to Freemason Brother John Gorst’s account of the 1863 evictions that occurred in the Manukau district, Rev. Purchas tried hard to persuade Māori of Mangere to take the oath of allegiance, “but could not shake them of their determination”.5 Bro. Gorst recorded the same answer returned at Pukaki and Ihumātao, in his 1864 book, The Maori King: The Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives. The Māori inhabitants of Ihumātao were served an ultimatum on July 10 1863 by Henry Halse and Henry Vercoe in the company of a few underlings. Bro. Gorst wrote this about passage about the pretext for evictions:

“the Government had not a single Maori policeman upon whose obedience they could depend. It was therefore resolved to drive these poor people men and women from their homes and confiscate their lands. There was no difficulty in finding a pretext. They were Maoris and relatives of Potatau.”

In his book The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, historian Vincent O’Malley states that on July 9th 1863, Henry Halse read Governor George Grey’s proclamation in the presence of Freemason Reverend Arthur Guyon Purchas and ‘native’ missionary Tamati Ngapora, who was a relative of Potatau II (Te Wherowhero’s son Chief Tawhaio), while on his way to the Māori villages in the Mangere district. O’Malley emphasized that the Waikato War really started at Ihumātao, before the shooting commenced a few days later when General Duncan Cameron’s troops crossing New Zealand’s version of Rome’s Rubicon River – the Mangatawhiri Stream – an awa that Governor Grey knew demarcated Waikato Māori territory and that if crossed it was a ‘point of no return’ – without provoking war.

Masonic Black-ops

During the peak period of the New Zealand Wars, British Prime Minister Freemason Lord Bro. Palmerston was for most of the time between 1837 and 1865, either the Foreign Secretary, at the British Government’s Foreign Office, or Home Secretary, when he was not wearing the British Prime Minister’s hat. According to non-establishment historians, Prime Minister Lord Bro. Palmerston was the top Freemason during the colonial period that coincided with the British takeover of New Zealand.

Historian Nicholas Hagger locates Lord Bro. Palmerston (born Henry John Temple, 1784) as a 33rd Degree Freemason at the top of secret Sionist-Rosicrucian English Freemasonry and a High Priest of Templar Scottish Rite Freemasonry and the Grand Master of British Brotherhood, and the ruler of all secret societies in the world during this period. While numerous ‘Famous Freemason’ biographical lists and accounts cite Thomas Dundas, 2nd Earl of Zetland, as the Grand Master of English Freemasons from 1844 to 1870. However, George Dillon stated in his 1885 book – Grand Orient Freemasonry Unmasked as the Secret Power Behind Communism – that hidden masters of the Brotherhood were served by skilled secret plotters scattered amongst the rank and file.6 During the Colonial-era of the British Empire, Queen Victoria was the Patronness of English Freemasonry and her husband George was a Freemason.7 Because the key oath of Freemasonry is one that obligates the fraternity to always follow orders from above, the merger of Freemasonry with the political-economic-cultural power bases of the British Empire meant obedience to a horrific imperial vision: universal empire.8

Indeed, historian Webster Griffin Tarpley described Lord Bro. Palmerston as the most powerful leader of the British oligarchy between 1830 and 1865, and the leading imperialist of his time, who was hell bent on forging a world empire. The British Prime Minister held an outrageously belligerent attitude to any native or colonist people who opposed the British Empire’s brotherhood – as Tarpley has retold. Lord Bro. Palmerston “thundered” in the British Parliament that wherever a British subject travels the British fleet will resolve his disputes.9 In his masterfully epic study of the United States from the American Revolutionary War to World War II – Treason in America – historian Anthony Chaitkin found that a secret network of British-Swiss-Dutch-Venetian plotters used Lord Palmerston’s family estate, Broadlands, as the headquarters for the British Masonic Empire’s ‘black operations’ to subvert rival powers, competing coalitions and indigenous peoples.10

Forebodingly for Māori – Lord Bro. Palmerston declared that British law would be respected in New Zealand before the outbreak of the Waikato War 1863-64 – even if it required 20,000 men to impose that ‘respect’.11

New Zealand’s First Gang

Bro. George Grey, who was initiated into Freemasonry in Ireland at the Military Lodge No.83, I.C., was of noble heritage. Bro. Grey’s cousin was the Earl of Stamford, whose ancestor had fought on the Parliamentary side of the English Civil War against the Royalists. When the First Taranaki War (1860-61) did not turn out to be an easy romp over ‘the natives’, Bro. George Grey was recalled from his Governorship in the Cape Colony, because he had proven himself an astute strategist, and knew New Zealand’s geography, the tribes, and was fluent in te reo Māori. The town of Auckland turned on the pomp for Bro. Grey’s return on 26 September 1861, with a crowd of 8,000, complete with bugles, riflemen and an official welcome – at the 13-acre Albert Barracks site on Fort Street.12

The Southern Cross newspaper, owned by land-swindler merchant John Logan Campbell, voiced fighting talk:

“Sir George arrives among us in September 1861, more powerful than any Governor that ever arrived in New Zealand. He has an army at his back, and colonists who have pledged themselves through their representatives to spare neither blood nor treasure in upholding her Majesty’s sovereignty.”

By Christmas 1861 and at a time when Governor Bro. Grey was faking peace he was planning war with General Duncan Cameron. Governor Bro. Grey had almost 2,500 soldiers that included Freemasons building a military road, lined with telegraph poles and copper wiring that would cut into Waikato territory as far as the Mangatawhiri Stream.13 In 1862, Brother Grey bought two steamers for conversion into gunboats to finish charting the Waikato River, charts that Bro. George Grey had started years earlier before he left New Zealand to oversee military operations in the Cape Colony. (In this task, Governor Bro. Grey was stopped by Tainui chiefs on the banks of the Waikato River, where he was told he was in Tainui territory, to turn around and to never return since he had no authority to be there, let alone to be surveying and charting the river). By Christmas 1862, General Cameron had 10,000 Imperial Troops under his command, a fact that ‘the Waikatos’ could hardly miss.14

On April 13 1863, three months before General Cameron crossed the Mangatawhiri Stream – Lord Bro. Palmerston appointed Freemason Bro. George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 3rd Earl de Grey, as Secretary of War. The Commander-in-Chief of British Armed Forces, HRH Prince George William Frederick Charles signed orders for the 43rd, the 50th and 68th Regiments to travel to the far-flung colony. Like Bro. George Grey, the 2nd Duke of Cambridge – Prince George – was also a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath [1855].15

These chivarlous orders were more than merely symbolic remnants of feudalism, because in the Colonial era they maintained the aristocracy, which supported the British Monarchy, and worked in tandem with the private political system – Cartel Capitalism – to keep as many people as possible from owning land. This is crucial context because all of the Maritime Powers of Europe – including Britain – exported their social problems to their colonies. In other words, the Rulers of Europe were unwilling to institute mass land reform and instead created the conditions for mass migrations to occur that would in turn create structural pressures leading to armed conflict between immigrant militias and the imperial forces on one side – and indigenous peoples’ on the other.

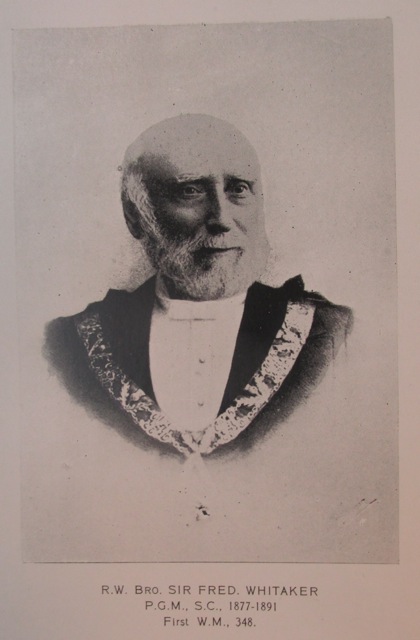

Where Lord Bro. Palmerston appointed Freemason Bro. Robinson, 3rd Earl de Grey, as Britain’s Secretary of War in April 1863 – New Zealand Premiere Bro. Frederick Whitaker appointed his business partner – Thomas Russell – in the Auckland law firm Whitaker and Russell, as Minister of Colonial Defence. As Colonial Defence Minister, Russell was in a position to allocate funds for the war.

Bro. Whitaker and Russell were key protagonists in the Natives Lands Act of 1862, which ended the Crown’s land-swindling monopoly on land purchases with Māori dating back to the fraud-ridden, rat-eaten Te Tiriti o Waitangi.16 Then, in 1863, Bro. Whitaker and Russell drove the ‘wedge of war’ deeper with three more parliamentary acts. The first was the Suppression of Rebellion Act of 1863, which for all intents and purposes upheld the fraud of Te Titiri o Waitangi of 6 February 1840, since the Māori version is the one that counts.17 The second piece of legislation that Masonic Bro. Whitaker and Russell schemed was the New Zealand Settlement Act, which legalized the establishment of military towns on land belonging to Māori that the Masonic fraternity’s Governor could construe were in rebellion against the Crown. And finally, the New Zealand Loan Act, that authorized ‘borrowing’ three million pounds to escalate the conflict that would be named, in the grand tradition of the British Masonic Empire, after those they gamed, blamed and shamed: ‘The Maori Wars’.18

Māori Prisoners and Refugee Population

There were two principle chiefs of the Manukau district. One rangatira was Chief Ihaka Takaanini te Tihi, who had resided at Pukaki, was of the Akitai and Uri-a-Taoa hapu groups, of the Ngati Tamaoho. Chief Mohi te Ahi-a-tengu of Te Akitai Waiohua tribe, whose ancient stronghold was the Pukekiwiriki had taken refuge at Te Aparangi village by the Kirikiri Stream, near Papakura, along with Chief Ihaka. On July 16 1863, Te Aparangi, the village and chiefs Ihaka and Mohi te Ahi-a-tengu were surrounded by twenty of Freemason Colonel Bro. Marmaduke George Nixon’s Otahuhu Calvary, forty of the Colonial Defence Force under Captain Walmsley and three hundred troops of the 65th Regiment under Colonel Murray.19

Following the outbreak of the First Taranaki War in March 1860, Colonel Bro. Marmaduke George Nixon, who was born in Malta and trained at Sandhurst Military College, was recalled from retirement and made Commanding Officer of two units of the Mounted Defense Calvary (later renamed the Royal Volunteer Calvary), that formed a line of defence across the Waitemata-Manukau isthmus, linking the Fencible settlements of Howick, Panmure, Ōtāhuhu and Onehunga. Bro. Nixon was also called upon to form a Colonial Defence Force when Bro. Governor Grey’s war plans for the tribes of the Waikato south of Auckland emerged.20

Bishop Selwyn, Freemasons Bro. Dillon Bell and Bro. John Gorst tried to persuade the rangatira to take an oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria on July 16. Chief Ihaka was evidently too sick to talk, and it was suspected he was lying on an arms cache hidden under a mat. Weapons were confiscated and Chief Ihaka and 22 other Māori were marched to ‘Camp Otahuhu’ – the military camp in Otahuhu. They were then shipped to on Motu-Hurakia, one of Governor Bro. Grey’s island prisons, or gulags, in the Hauraki Gulf. All but two died of sickness, as a consequence of malnutrition amid winter conditions.21

While Māori of the Manukau district were selling what livestock, produce and other possessions they could before they left, 17 waka from the Manukau Region were confiscated by 39 Auckland Naval Volunteers and twenty-five ‘friendly natives’ in a week long expedition. According to historian T. B. Byrne in his 1991 book, Wing of the Manukau, the civil and military authorities viewed the Manukau Harbour as a security risk, since the port at Onehunga was considered “Auckland’s backdoor”.

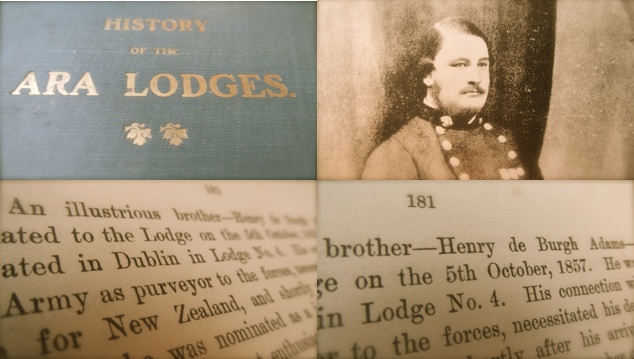

Like other strategically important locations, a Masonic Lodge was established at Onehunga on 16 December 1863, by Freemason Major Bro. Henry De Burgh Adams who was Purveyor to the Armed Forces. Major Bro. De Burgh Adams had been deployed to New Zealand in 1857 as Britain withdrew from the Crimean War.22

The Monday 27 July 1863 edition of the New Zealander newspaper reported that at ‘Ikumatu’ [Ihumātao] and ‘Oruringa’ [Oruarangi] four canoes were taken on 23 July, along with four waka at Pukaki, adding to the spoils of 14 waka for the week. General Duncan Cameron would later order that these canoes be destroyed with explosives. With no means of water transport left, the evicted Māori had no option but to walk over land southward to the Waikato.23

‘Rebellious Natives’: While the peaceful Māori of Ihumātao were preparing to leave, four waka from Ihumātao and Oruarangi were confiscated by the Auckland Naval Volunteers.

In this callous way, the ultimatum issued by Freemason Governor Bro. George Grey produced a Māori refugee population from Mangere, Pukaki and other villages of Tamaki Makaurau whom were forced to walk into the Waikato Region. Grey’s demand for an oath of allegiance was not unlike the submission expected of a Freemason to always follow orders from above.24 Except, that Māori never ceded sovereignty in 1840 – regardless of whether or not they signed the Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown, and were therefore not British subjects, nor were ‘the Natives’ in rebellion.25

Bro. George Grey – whose entry into the world was premature due to his pregnant mother overhearing news that her husband had died in battle serving under the Duke of Wellington against Napoleon I – was honoured with a state funeral and buried in a crypt in St Paul’s Cathedral in London on 26 September 1898, close to the tomb of the Duke of Wellington. In other words, Governor Bro. Grey’s war-traumatized mother gave birth to a son who grew up to be a shrewd war strategist, and who spread war trauma in a far-flung colony, and for his service to his secret Masonic Brethren he was exalted with a resting place in a Church of England cathedral designed by a key founder of English Freemasonry, Christopher Wren.

Key positions in the political, commercial and martial institutions were not simply filled by men who just happened to be Freemasons. As Freemasonry’s own endorsed voice, Jessica Harland-Jacobs, found in her study spanning 130-years – Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927 – the British Empire was spread by Freemasonry and mostly through the military regiments of the Royal Navy and Army.

Therefore, Ihumātao is a place of national significance because it is the location of the Waikato War’s first evictions that were the result Masonic plotting. The intention of the Waikato War was to smash the Māori communal economy and consolidate the Realm of New Zealand as a Masonic Colony. It also poignant that Ihumātao was the location where the first Māori King, Potatau Te Wherowhero, was elected in mid-1857.26

======

Editor’s Note: Please let me know if I have made any errors.

e: steveedwards555@gmail.com

The Masonic New Zealand Wars: Freemasonry as a Secret Mechanism of Imperial Conquest During the ‘Native Troubles’

Referenced Sources:

1 Vincent O’Malley. (2015). The Great War for New Zealand – Waikato 1800-2000, p. 206. Bridget Williams Books.

2 Snoopman. (April 25, 2017). The Masonic New Zealand Wars: Freemasonry as a Secret Mechanism of Imperial Conquest During the ‘Native Troubles’. Retrieved from https://snoopman.net.nz/2017/04/25/the-masonic-new-zealand-wars/

3 Harland-Jacobs, Jessica. (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927. The University of North Carolina Press.

4 Their hell-bent vision competed with a rival Brotherhood, French Templar Freemasonry. British Freemasonry was Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry, which founded a United Grand Lodge in 1717 to unify English resistance to Jabobite Templar Freemasonry, that formed around the Scottish Stuart dynasty, who were formally and permanently banished the same year from the British Isles. It was at this point, in 1717, when Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry came to rule over the British Monarchy and the Church of England, after having successfully achieved a political and business merger with the Dutch in 1688. Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry is a revolutionary force committed to forging a universal empire under the rule of one monarch, while French Templar Freemasonry developed into a revolutionary force committed to forge a universal empire under the rule of one federal republic. See: Nicholas Hagger. (2005). The Secret History of the West: The Influence of Secret Organizations on Western History from the Renaissance to the 20th Century.

5 John Gorst. (1864). The Maori King: The Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives, p.246.

6 Daniel, John. (1994). Scarlet and the Beast. Vol. 1: A History of the War between English and French Freemasonry, p. 227. Tyler, Texas, USA: Jon Kregel, Inc; Hagger, Nicholas. (2009). The Secret Founding of America: The Real Story of Freemasons, Puritans & the Battle for the New World, p. 183. London, United Kingdom: Watkins Publishing; Hagger, Nicholas. (2005). The Secret History of the West: The Influence of Secret Organisations on Western History from the Renaissance to the 20th Century; p. 373. Winchester. UK: O Books; Executive Intelligence Review. (1978). Dope, Inc: Britain’s Opium War Against the World, p.25-26, 28, 243; Tarpley. (1994). The Palmerston Zoo: Solving the Paradox of Current World History. In: Palmerstons Zoo Introduction Webster Tarpley part 1. Schiller Institute/ICLC Presidents Day Conference. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8G2BkV3cL9Y

7 Harland-Jacobs. (2007). Builders of Empire, p. 254; Appendix: Royal Freemasons. In: Harland-Jacobs. (2007). Builders of Empire.

8 Harland-Jacobs. (2007). Builders of Empire; Bro. Col. George Barclay. (1933). “The Soldier and Freemasonry”. p 71.

9 Tarpley. (1994). The Palmerston Zoo: Solving the Paradox of Current World History. In: Palmerstons Zoo Introduction Webster Tarpley part 1. Schiller Institute/ICLC Presidents Day Conference. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8G2BkV3cL9Y; Webster G. Tarpley. (Feb. 22-23, 1992). The British Empire Bid for Undisputed World Domination, 1850-1870. Schiller Institute Food For Peace Conference, Chicago, IL. Retrieved http://tarpley.net/online-books/against-oligarchy/the-british-empire-bid-for-undisputed-world-domination-1850-1870/; Webster G. Tarpley, Ph.D. Lord Palmerston’s Multicultural Human Zoo Against Oligarchy

Lord Palmerston’s Multicultural Human Zoo

10 Anthony Chaitkin. (1985). Treason in America: From Aaron Burr to Averell Harriman.

11 Chappell, N. M. (1961). New Zealand Banker’s Hundred, p. 9-10.

12 Gavin McLean (2006). The Governors: New Zealand’s Governors and Governors-General, p. 62; Dom Felice Vaggioli. (2000 [1896]). History of New Zealand and its Inhabitants, Vol. II, 134. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press.

13 Bro. G.A. Gribbin. (1909). A History of the Ara Lodges, p. 124; Tony Simpson (1979). Te Riri Pakeha: The White Man’s Anger. p.148; Tom Gibson (1974). The Maori Wars, p. 96-97.

14 Tony Simpson. (1979). Te Riri Pakeha, p.147, 153.

15 Bro. G.A. Gribbin (1909). History of the Ara Lodges, p.123; 125–26; Weston (1942), Centennial History of the New Zealand Pacific Lodge No. 2, p.44-45; Bro. Barclay (1936). The Extinct Lodges of New Zealand, p. 80; “Famous Freemasons From New Zealand and Around The World – Charles Heaphy VC (1820 – 1881)”. Ruahine: View to the East. Vol. 3 Issue 4; Belich (1998). The New Zealand Wars, p.148; http://www.themasons.org.nz/ruahine/may14/may.htm

16 Simpson. (1979). Te Riri Pakeha p.161-162.

17 The Māori language version of the Treaty was re-written on the night of February 5 by the land-swindling protestant missionaries Reverends’ Henry and William Williams, to persuade the chiefs to sign. It was this version that was read out to Māori on February 5 at Waitangi. Māori had not ceded sovereignty to the British Crown. As Stevan Eldred-Grigg wrote in The Rich: A New Zealand History, “Henry Williams, a ‘well connected’ naval lieutenant appointed Anglican missionary to the Bay of Islands, who emigrated with his Cambridge graduate brother William and worked busily in the 1820s savings souls and acquiring property in Northland”. p. 24-25.

18 Tony Simpson 1979 Te Riri Pakeha p.163-164.

19 Tonson. (1966). Old Manukau, p. 68-69. Onehunga, Auckland; New Zealand: Tonson Publishing House.

20 From Bush to Borough R.A. Baker 1987: 8, 26; Barclay 1935, Extinct Lodges: 82; Vaggioli 1896: 111); Military camp for Imperial forces at Otahuhu, Between 1860-1865 Great Britain. Army. 40th Regiment of Foot (2nd Somersetshire), Great Britain Army 12th Regiment of Foot (East Suffolk), Camp of Imperial Forces, Great Britain Army 14th Regiment of Foot (Buckinghamshire-Prince of Wales’s Own), Great Britain Army 70th Regiment of Foot (Surrey), Otahuhu and Military camps – New Zealand – Auckland Region. National Library of New Zealand. Reference Number: PA1-q-250-28. Retrieved from: http://mp.natlib.govt.nz/detail/?id=12707&l=en

21 TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA HISTORY. Retrieved from http://www.teakitai.com/index.php/history.

22 Bro. G.A. Gribbin. (1909). The History of the Ara Lodges, p. 181; Snoopman. (April 25, 2017). The Masonic New Zealand Wars. Retrieved from https://snoopman.net.nz/2017/04/25/the-masonic-new-zealand-wars/

23 T. B. Byrne. (1991). Wing of the Manukau: Capt. Thomas Wing: His Life and Habour 1810-1888, p. 297-298. Auckland, New Zealand: T. B. Byrne.

24 Martin Short. (1989). Inside the Brotherhood: Further Secrets of Freemasons. London, UK: Grafton Books. p.136; Stephen Knight (1984).The Brotherhood: The Secret World of the Freemasons. UK: Granada Publishing; Harland-Jacobs, Jessica (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927.

25 Waitangi Investigation: Steve Edwards – Harnessing the Herd to Hide a Historical Heist: The Crown’s breach of the Crimes Act. https://thedailyblog.co.nz/2018/02/06/waitangi-investigation-steve-edwards-harnessing-the-herd-to-hide-a-historical-heist-the-crowns-breach-of-section-the-crimes-act/; Harnessing the Herd to Hide a Historical Heist https://snoopman.net.nz/2018/09/18/harnessing-the-herd-to-hide-a-historical-heist/

26 Snoopman. (27 July 2019). The Deep History of Ihumātao: The Kingitanga Connection. Snoopman News. Retrieved from https://snoopman.net.nz/2019/07/27/the-deep-history-of-ihumatao-the-kingitanga-connection/