An Essay revealing Britain’s Two-Track Takeover Strategy, the Fulcrum of Language Translations & the Treaty Cliqué’s Theatre now re-packaged as sanitized Disney Treatyland Waitangi Lite

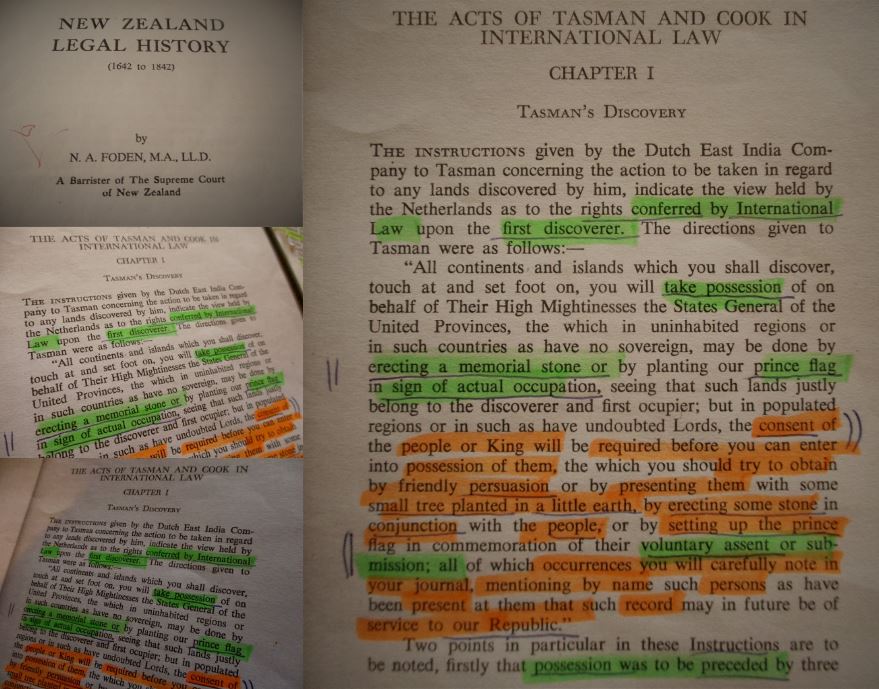

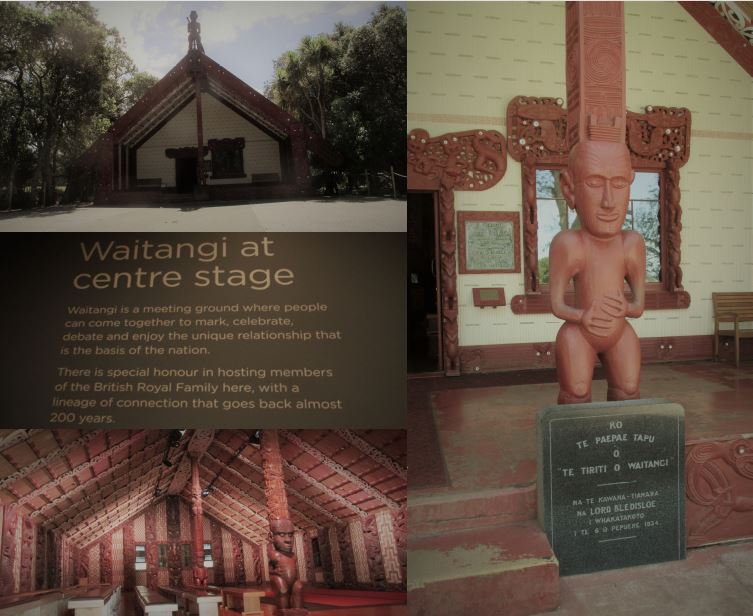

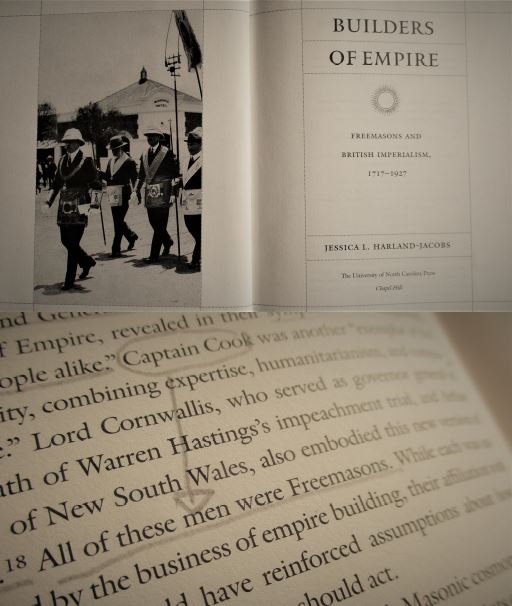

This white paper shows that two parallel tracks – a ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ and a ‘Colonial Law Track’ – were laid during the British takeover of New Zealand. Three ‘Clanker Moments’ at Waitangi prove that a Treaty Cliqué consciously avoided fully disclosing to Māori there was trickery afoot, with a Theatre production that proceeded with unseemly haste. Because the Treaty parchments spun on a fulcrum of deceptive language translation differences, the Cliqué later construed that the Treaty Chiefs had consciously and freely signed away sovereignty. Moreover, Māori at Waitangi were unaware that a secret piece of international law, known today as the Doctrine of Discovery, was applied during the 1840 Waitangi Treaty Theatre. This Discovery Doctrine was ‘transported’ on both tracks, and intersected briefly at Waitangi, where time had been weaponized to gain control over a new territorial-jurisdictional space for the British Masonic Empire. Whereas, the Colonial Law Track was the primary route through which the completion of the annexed title claimed by Freemason Bro. Captain James Cook actually occurred. Indeed, the ‘Endeavour Voyage’ in 1769-1770 was New Zealand’s first travelling theatrical production and the Waitangi Treaty Theatre was staged to distract, divide and defeat.

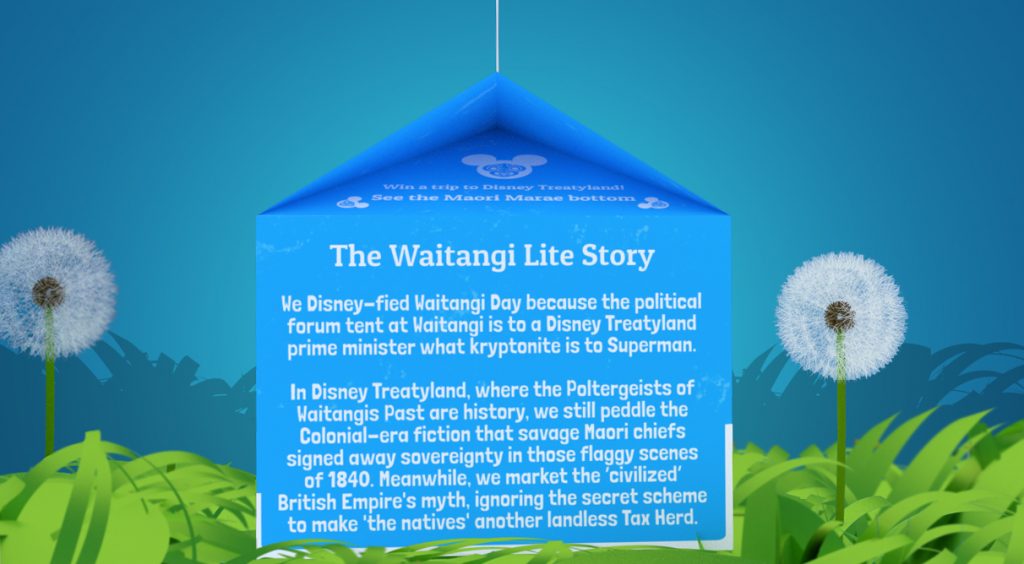

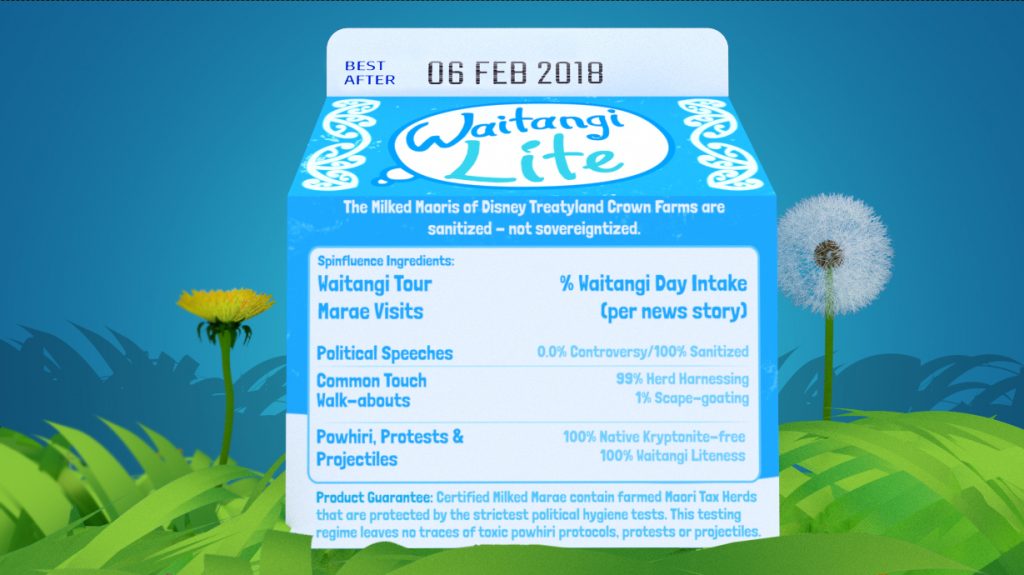

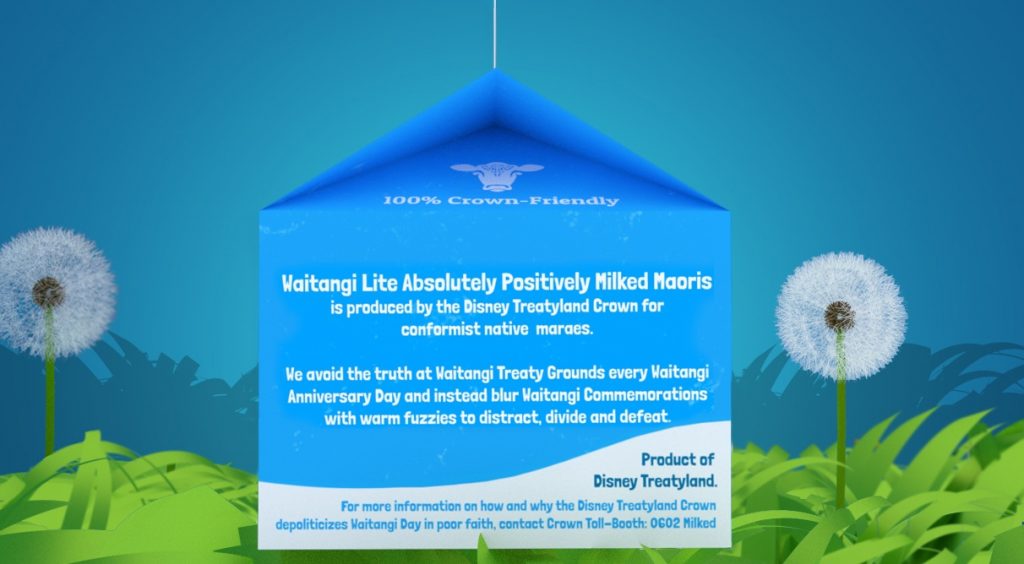

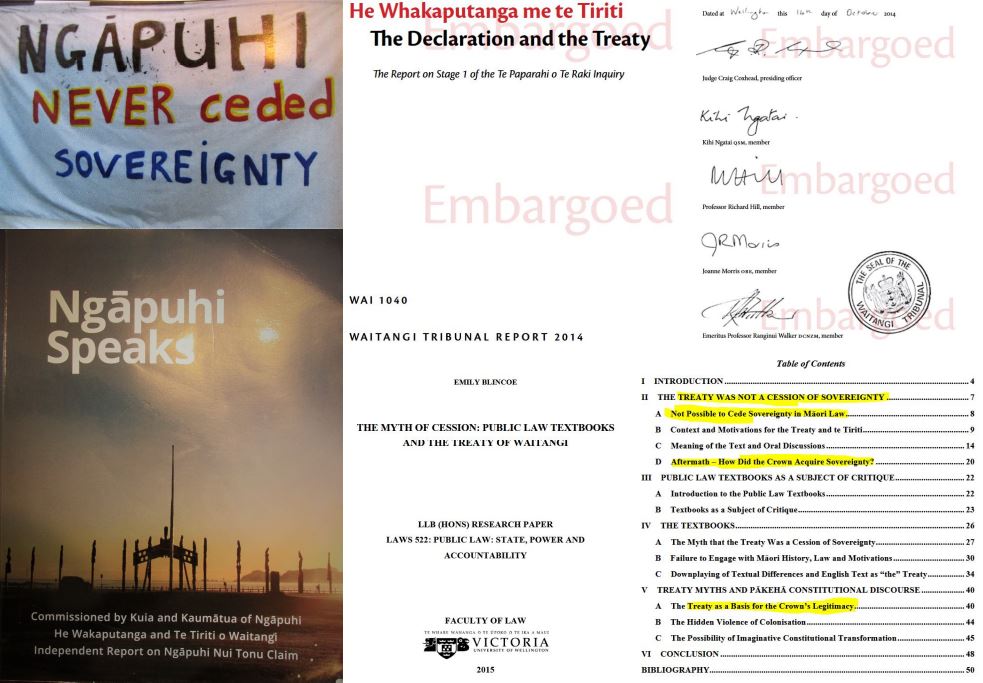

At the beginning of 2020, the New Zealand Crown plays an unsound, unsafe, and unwise contrived ignorance game by avoiding admission to the nation that Māori rangatira did not sign away sovereignty to the British Crown in 1840, despite the findings of the Ministry of Justice’s Waitangi Tribunal in 2014. In playing this contrived ignorance game, the Crown avoids admission to a grand Treaty Truth-out Show because it has invested heavily in covering-up Britain’s two-track takeover strategy, the fulcrum of deceptive language translations and the Treaty Cliqué’s Theatre to sell Captain Hobson’s ‘One People’ Snake Oil. This investment resulted in the Key and English ministries re-packaging the ‘Myth of Cession’ as a sanitized Disney Treatyland Waitangi Lite, which the Ardern Coalition Ministry markets at its own peril. The Māori Renaissance has cultivated confidence, resourced rūnanga and spirited solutions that aspire to forge self-determining communities based on Māori land tenure. Meanwhile, the Crown’s contrived ignorance game assumes the days of its sole sovereign power status have not been numbered with a countdown.

“Kua mau tātou ki te ripo. Kāti ka taka ki tua o te rua rau tau ka tū mai te pono ki te whakatika i nga mea katoa”.

“We have been caught in a whirlpool. Alas, it will last for beyond 200 hundred years when the truth will stand to put everything right”. – Prophet Papahurihia after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, 1840i

The Snoopman

Crown Contrived Ignorance about Mowing Over Native Sovereignty in 2020

New Zealand’s Government continues to refuse to admit that Māori chiefs did not wittingly cede sovereign power in 1840 – and is, therefore, in breach of section 240 of the Crimes Act, which deals with crimes of deceit.ii

This breach of section 240 of the Crimes Act occurs because the Crown continues to ignore the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal’s October 2014 report, that Ngāpuhi and other Treaty Chiefs did not cede sovereignty in 1840.

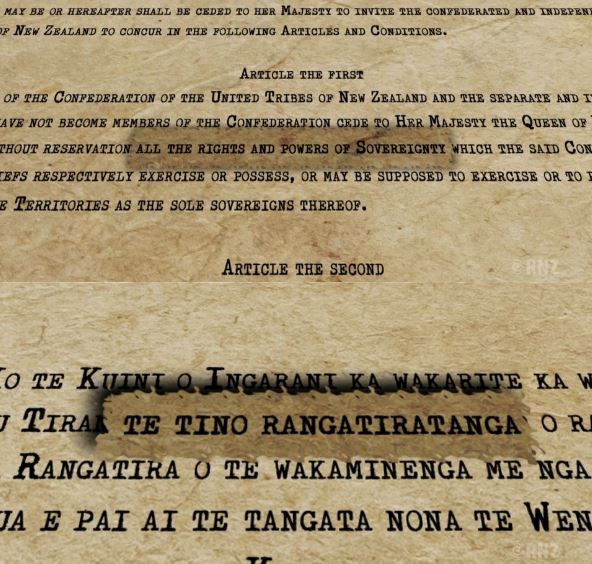

The key finding of the Ministry of Justice’s Waitangi Tribunal was that the Ngāpuhi Treaty Chiefs believed they were conferring Queen Victoria the right to appoint a governor to rule over Pākekā, and, therefore, did not wittingly sign away their mana and tino rangatiratanga, or sovereign powers and authority.iii Both mana and tino rangatiratanga were regarded as paramount, spiritually sanctioned, inalienable power, as Emily Blincoe noted in her 2015 Victoria University Faculty of Law paper, “The Myth of Cession: Public Law Textbooks and The Treaty of Waitangi”, which found that leading New Zealand law textbooks mislead law students by advancing the cession by treaty narrative.iv Not only did the Waitangi Tribunal explore the meanings ‘lost in translation’ between the English and Māori language versions of the Treaty of Waitangi. The Ministry of Justice’s Waitangi Tribunal also noted the crucial assurances of Lieutenant-Governor Hobson, his agents and the Protestant missionaries – given to rangatira: (1) Queen Victoria would not dispossess Māori of their lands they did not willingly sell; (2) Māori would not become enslaved; and (3) rangatira would still retain their chiefly authority.v

From October 2014 to October 2017, the Key and English Ministries pursued a deceptive exclusionary black-balling strategy to distract, divide and defeat Ngāpuhi and other Northland iwi and hapū, in order to avoid acknowledging that the Waitangi Tribunal’s October 2014 report – was correct in finding that there was no cession of sovereignty in 1840.vi

To this end, NZ PM’s, John Key and Bill English, boycotted Waitangi in 2016 and 2017, respectively, after hosting the signing of the Trans-Pacific Economic Bloc Treaty two provocative days before Waitangi Anniversary Day 2016, in order to scapegoat Te Tii Marae. The subversive objective was to de-politicize Waitangi Anniversary Day, attack the mana of Ngāpuhi to coerce the Northland iwi to cede sovereignty by settling with the Crown, and corporatize the tribes of Northland through the activation of this malicious scape-goating mechanism – as The Snoopman showed in a two-year investigation, “Harnessing the Herd to Hide a Historical Heist” – first published on Waitangi Day 2018.vii

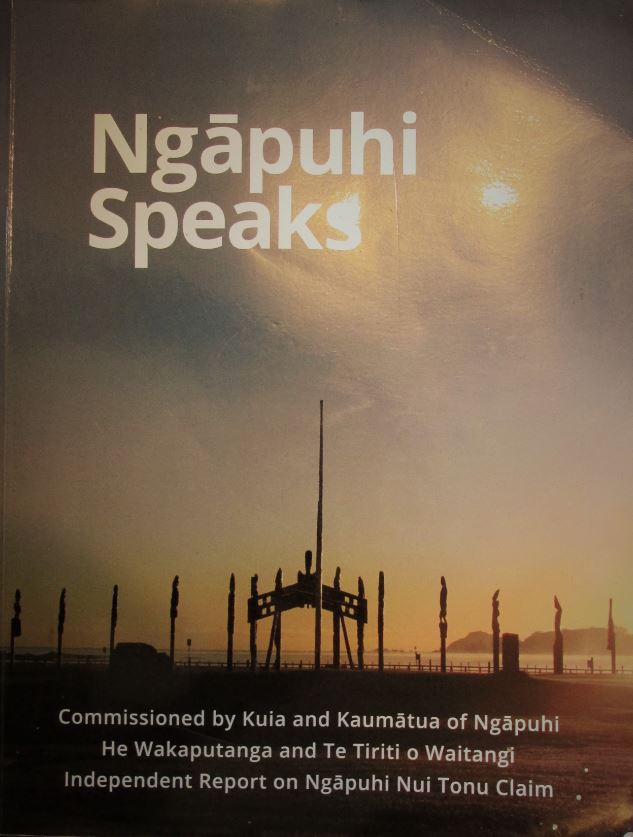

Today, the New Zealand Crown denies New Zealanders, including indigenous Māori, the right to full disclosure, not only about the stealthy application of the Discovery Doctrine by the British 250 years ago, when Freemason Captain Bro. James Cook recorded he claimed possession in two places on the Endeavour Voyage. But also, the New Zealand Crown continues to pursue the unlawful, unsound and unwise course set by the Key Ministry when then-Treaty Negotiations Minister Chris Finlayson, Prime Minister John Key and others, whom opted to ignore the Waitangi Tribunal 2014 report, as well as Ngāpuhi’s own commissioned field study, Ngāpuhi Speaks.

This fiction that the Treaty Chiefs ceded sovereignty to the British Crown in 1840 continues because the Crown wishes to sustain its outsized sole sovereign power over Māori. If the Crown were to very publicly admit that cession by treaty is a myth, and explain – with full disclosure – the how, the who and the why exactly, that the Treaty Theatre worked in tandem with a parallel Colonial Law Track, then it would face significantly diminished power. Given the Crown’s continued course of reckless contrived ignorance about the ‘Myth of Cession’, it is no small wonder that the Ardern Coalition Government invited Prince Charles to visit in mid-November 2019. The Royal visit to New Zealand by the neo-feudal billionaire, The Prince of Wales, and The Duchess of Cornwall, is shown to be a charm offensive, crisis intervention, and legal exercise to maintain the hereditary rights of the British Monarchy over the Realm.viii

The New Zealand Crown has recklessly contrived its own ignorance by pretending it does not know about the British Crown-scripted Myth of Cession. The Government’s game of pretend means it also avoids ‘fessing-up’ to the power crimes inherent to the British Masonic takeover of New Zealand.ix

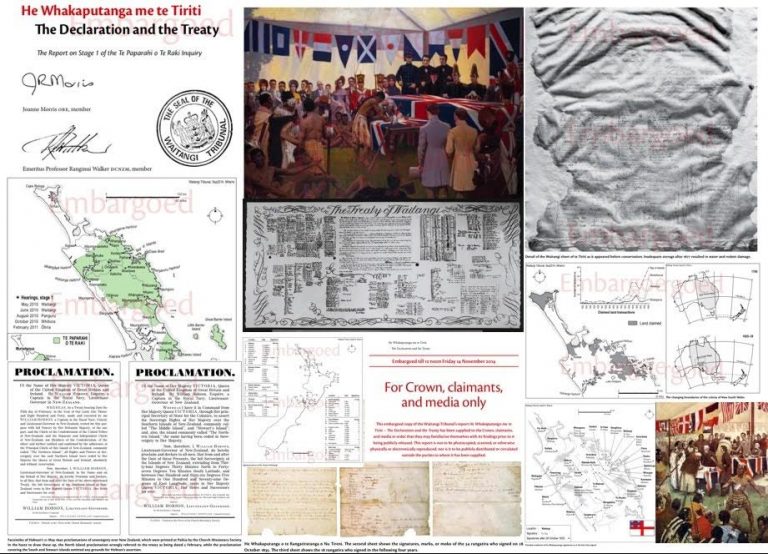

By avoiding the Waitangi Tribunal’s report – “He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti: the Declaration and the Treaty” – the Ardern Administration has, in essence, performed screening acts that ‘fail to see’ Māori were cleverly, callously and conspiratorially swindled out of possessing jurisdiction powers over their ancestral spaces – in perpetuity – with pieces of paper, pens and presents, as this investigation shows.

Screening actions are intentionally performed to avoid looking, whether institutionally, or individually, and when deftly executed at the right moments, they can very effectively sponsor subsequent unwitting misdeeds, as David Luban discussed in his 2007 book, Legal Ethics and Human Dignity, and as he modelled for his paper “Contrived Ignorance”, published in The Georgetown Law Journal in 1999.x Luban proposed viewing the version of the self that wittingly performed screening actions to preserve his own oblivion as the principle actor, while the agent is the later self at the time of the unwitting misdeed, who effectively ratifies the earlier self’s choice to compartmentalize, or screen off, potential knowledge of wrongdoing. Luban argued the case for modelling the, “Structure of Contrived Ignorance” by viewing screening actions and so-called unwitting misdeeds as a unitary whole rather than separated by time-frames.

In making his point that, “in criminal law, willful ignorance is ground for conviction, rather than acquittal,” Luban was in essence, laying out the gaps in catching and convicting group enterprises that contrive ignorance. A quote he draws from a U.S. trial seems apt for this case study of British Colonial state formation in a New Zealand context: “Ostriches … are not merely careless birds.”

Luban’s model for contrived ignorance can be used in the contemporary period to catch and convict individuals, institutions and inter-group networks contriving their ignorance to avoid admitting that the Treaty Chiefs were tricked into marking or signing the 1840 Treaty sheets, so that the British Crown could construe that sovereignty had been ceded voluntarily and wittingly.

By such contrived pretenses, those screening actions of failing ‘to see’, actually ‘author’ subsequent unwitting misdeeds, such as another iwi and hapū being coerced to behave accept the Crown’s captivity at the end of long drawn-out proceedings spanning many years. Because the Fourth Estate Media cartel acts like the Crown’s sale and purchase agents selling amplified problems blown out of proportion and neatly packaged highly restricted solutions, this serialized show called ‘the news’ works to brainwash their audiences in order to protect the other three estates. In the Realm of New Zealand, the Four Estates refer to the legislature, administration, judiciary and the journalism. This idea of estates of the realm is derived from the French Ancien Régime when Christendom was the ideological framework that dominated Europe. In feudal kingdoms, the realms were divided into three broad orders as systems of social control. The clergy comprised the First Estate, above which sat the Absolute Monarchy, while the nobility formed the Second Estate as a magisterial class ministering over royal justice and civil government, and the bourgeoisie and peasants comprised the Third Estate.

In Neo-Feudal New Zealand, most serf-level Pākehā are oblivious to the Stockholm Syndrome-esque appreciation that many Pākehā Ruling Class élites expect as their entitlement in their encounters with Māori, even as their institutions play Māori with the deployment of exclusionary blackballing strategies, deflection tactics and the performance of Discovery Doctrine-embued rituals. Concurrently, the Crown seeks to avoid a noisy-amplified discussion about how exactly and why exactly private land buybacks became a scared cow issue, and therefore, the N.Z. Government to maintain its institutionally racist, structural stonewalling machinary of state – as The Snoopman showed in “Fraught Precedents for Land Buy-Backs”.

This racist, criminal and repugnant status quo means the bulk of the brainwashed New Zealand people fail to realize the Neo-Feudal Crown’s game is to remain the sole sovereign power of this Neo-Feudal Realm. Meanwhile, it is transformed into a ‘Switzerland of the South Pacific Utopia’ for centimillionaires, billionaires and trillionaire transnationals to exploit cheap labour, treat as a test lab and transform into a foreign currency ‘blood funnel’ for giant banking squid.

This brainwashing works as a short-circuiting mechanism that prevents Tauiwi New Zealanders – including those Pākehā whom have been conditioned to be racist – from seeing that a Māori people resourced with sovereign land titles, would be a bulwark to prevent everyone else getting screwed by the Pākehā-dominated Neo-Feudal Rich-Lister Oligarchy, their Pākehā Ruling Élites and their land-grabbing international Investorati.

In the rest of this white paper, The Snoopman proposes to identify a Treaty Cliqué responsible for the British takeover of paper sovereignty in the period leading up to, during and in the immediate aftermath of ‘The Great British Waitangi Treaty Swindle’. He applies power crime theory to identify those who would be liable for prosecution if this vampiric conspiring group enterprise had not already joined the ‘Realm of the Undead’. Élite criminals exploit the speed of high-velocity engineered events to distort perceptions about the facts of events that overtake “low velocity political deliberation and public accountability”, as Monash University senior lecturer of public international law Eric Wilson has found in a contemporary context in his studies of ‘Shadow Government’ phenomena. It is in this way, that “politics ‘disappears into aesthetics’ ” – as Wilson puts it.xi The supposition presented here is that the Treaty Cliqué weaponized the one physical dimension they could control, as they raced toward the endgame to capture new political space via a sovereignty payload: time.

In his paper “The Phoenix Cycle: Global Leadership Transition in a Long-Wave Perspective”, Joachim Karl Rennstich drew upon Giovanni Arrighi’s metaphor of ‘track-laying vehicles’ in this 1994 book, The Long Twentieth Century: Money Power, and the Origins of Our Times. Arrighi described how the modern world system was constructed by public state and private enterprise complexes that activated ‘switches’ to new ‘tracks’. Rivalrous major powers invent new tricks to gain supremacy. Therefore, this paper “Paper Sovereignty Swindle in 1840 & the Crown’s Contrived Ignorance in 2020” looks at the 1840 Waitangi Treaty clustered events as part of a broader innovation of trickery – treaties with indigenous peoples – and with a novel twist of swindling full sovereignty by doing so in the language of the imperial power, while full sovereignty was retained in the native language version.

Therefore, the key omissions the 1840 Waitangi Treaty texts, rhetoric and context are located in power crime theory to identify the Treaty Cliqué. In the next section, ‘British Takeover by Two Parallel Tracks’, The Snoopman shows how a ‘Colonial Law Track’ and a ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ – were laid during the British takeover of New Zealand.

The supposition explored in this white paper is that Māori chiefs, hapū and iwi were manipulated by the British through incremental steps along a track to treaty, in which they were led to believe that by their own agency in such steps that they would retain their mana and tino rangatiratanga, or sovereignty authority, as self-determining people. In other words, a long-game was played, where time was ‘quickened’ around such events so that the British side achieved their objectives at every incremental step through this periodically sped-up dimension, by weaponizing dawn to dusk until the job was done and dusted.

British Takeover by Two Parallel Tracks

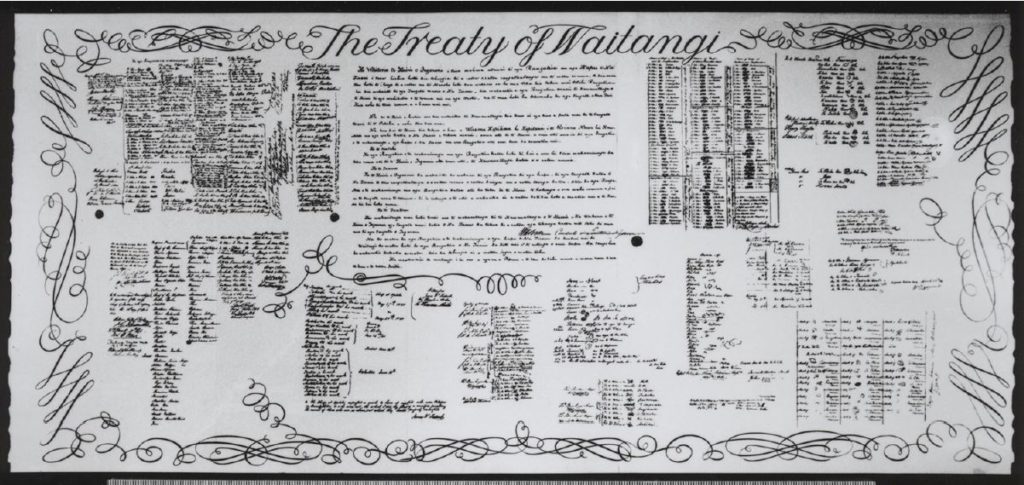

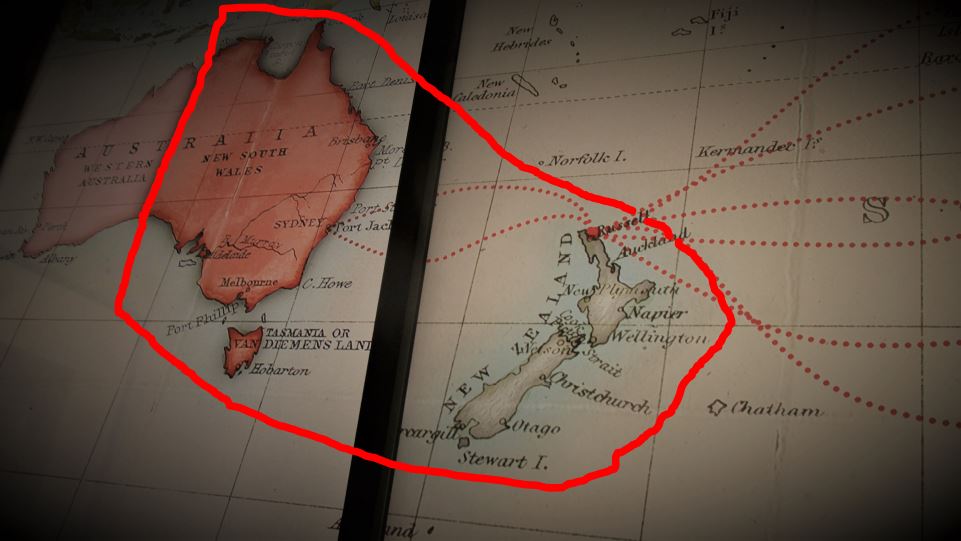

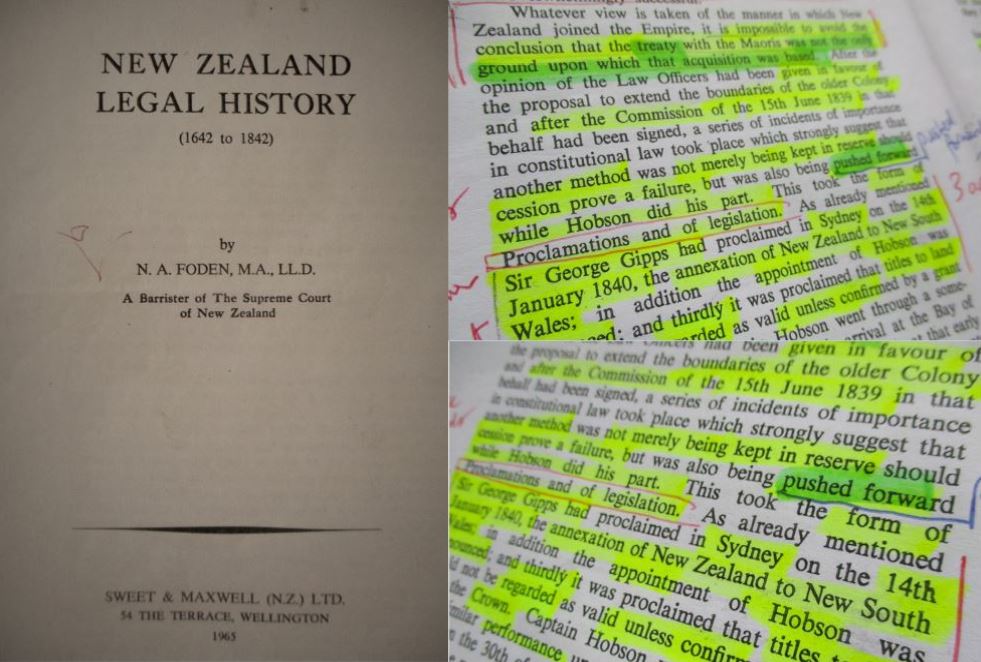

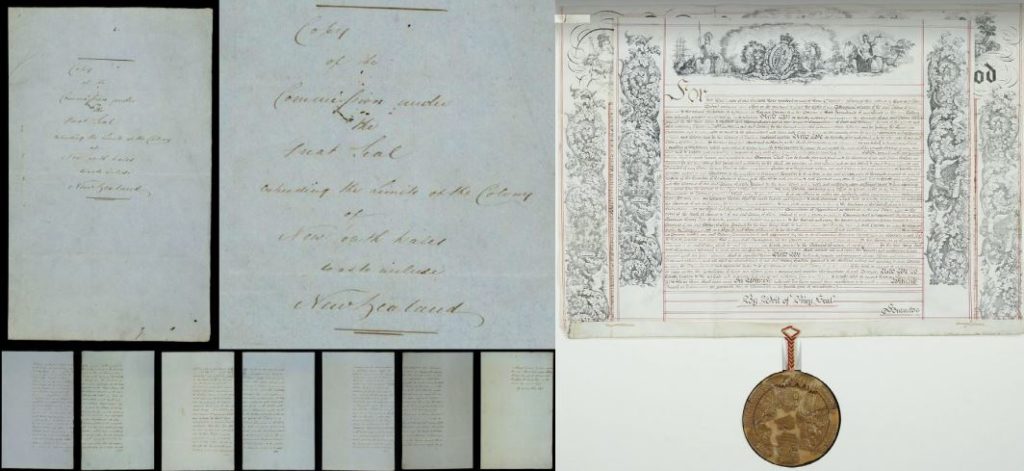

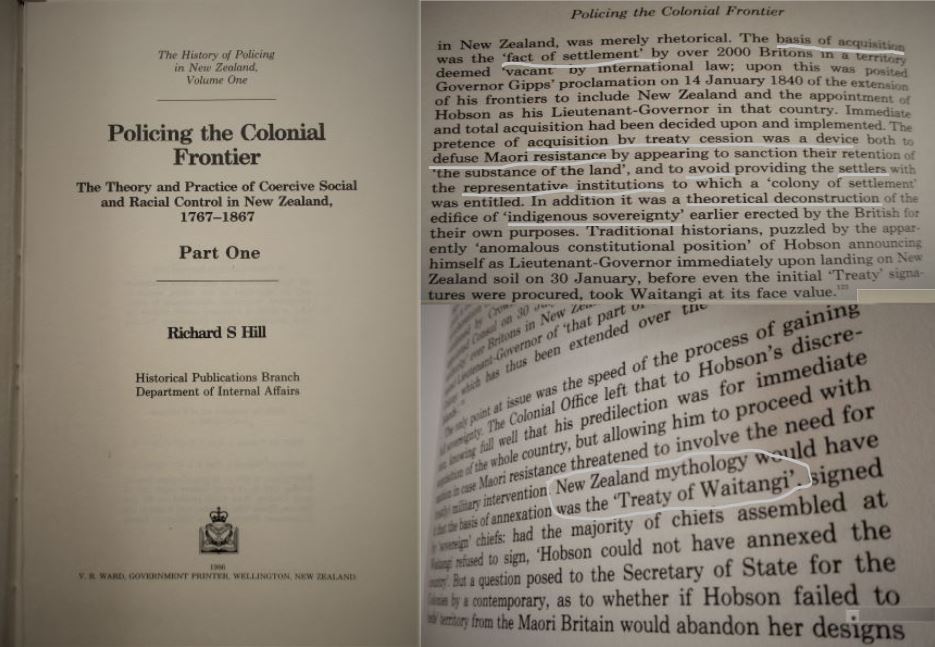

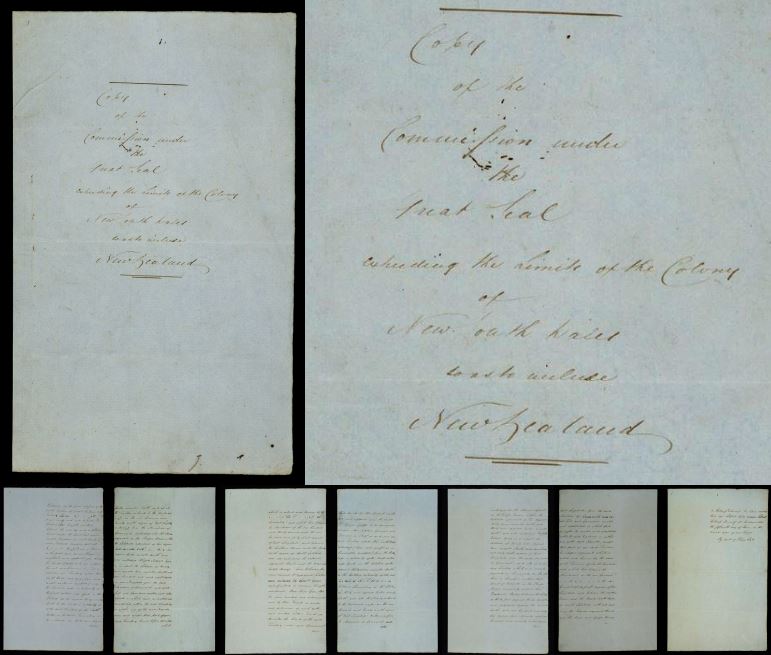

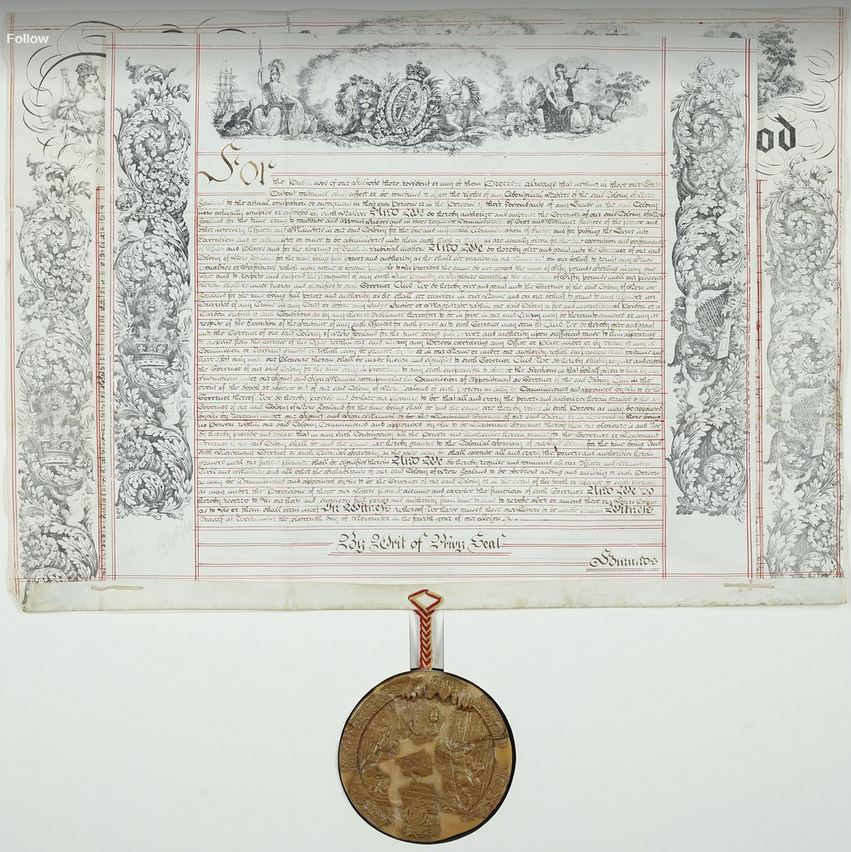

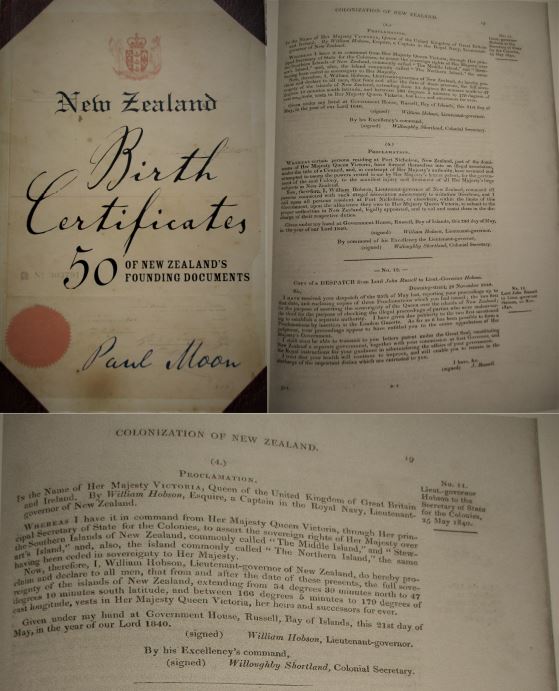

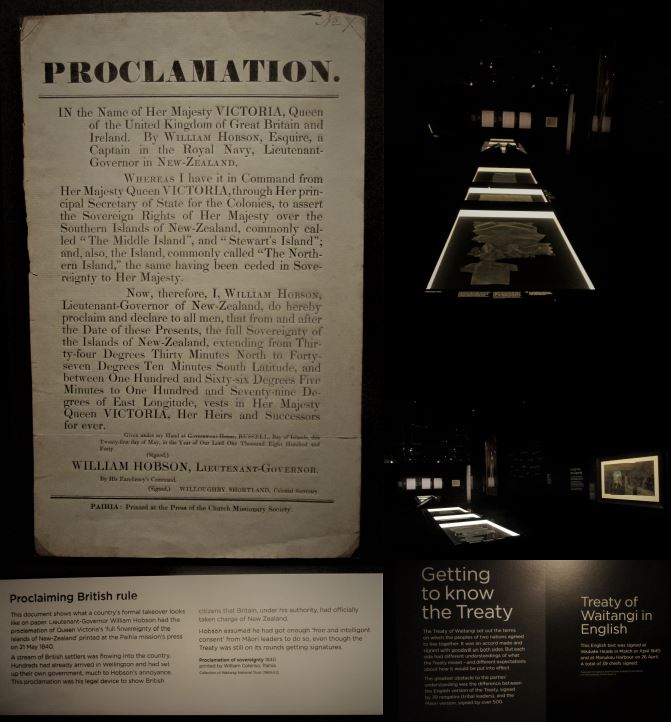

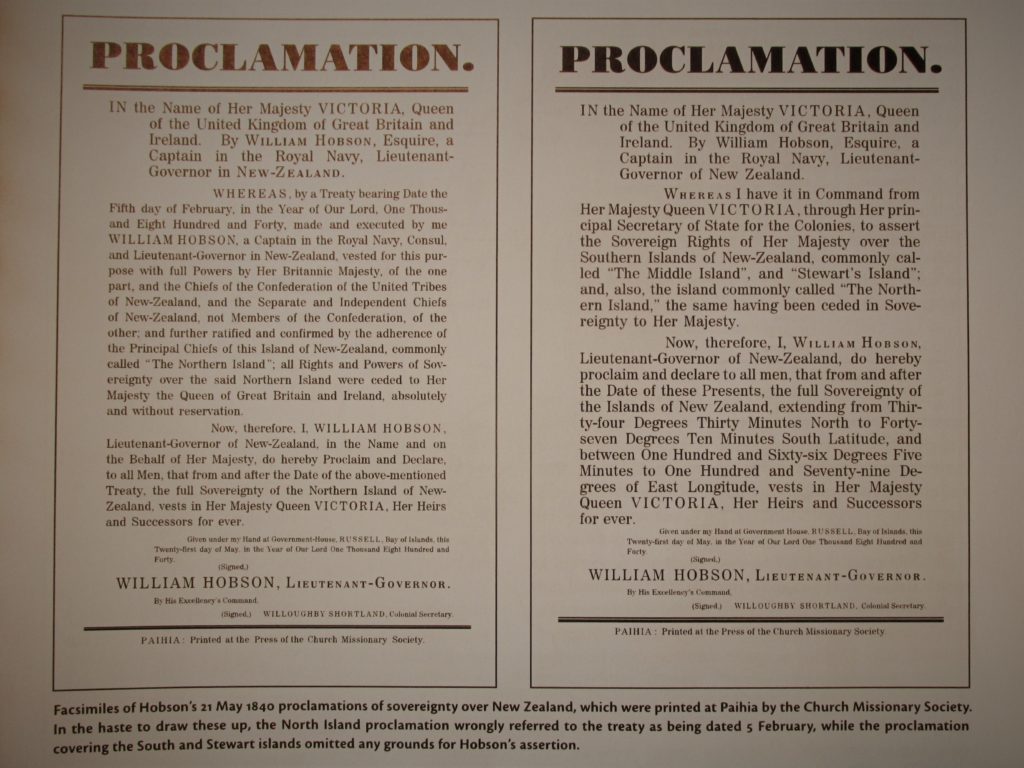

It turns out, two parallel tracks – ‘Treaty Theatre Track’ and a ‘Colonial Law Track’ – were laid during the British takeover of New Zealand. The main trunk line of the Colonial Law Track was laid in 1839 and 1840, with the roll-out of legal instruments prior, during and after the hasty hawking of the nine Treaty parchments around New Zealand coast-lines to swindle to 527 Māori rangatira and 13 wahine signatures and marks. The legal instruments included proclamations, new commissions, swearing-in officials, letters patent, legislation, gazetted notices and a royal charter that solidified the establishment of New Zealand as a separate colony of the British Masonic Empire.

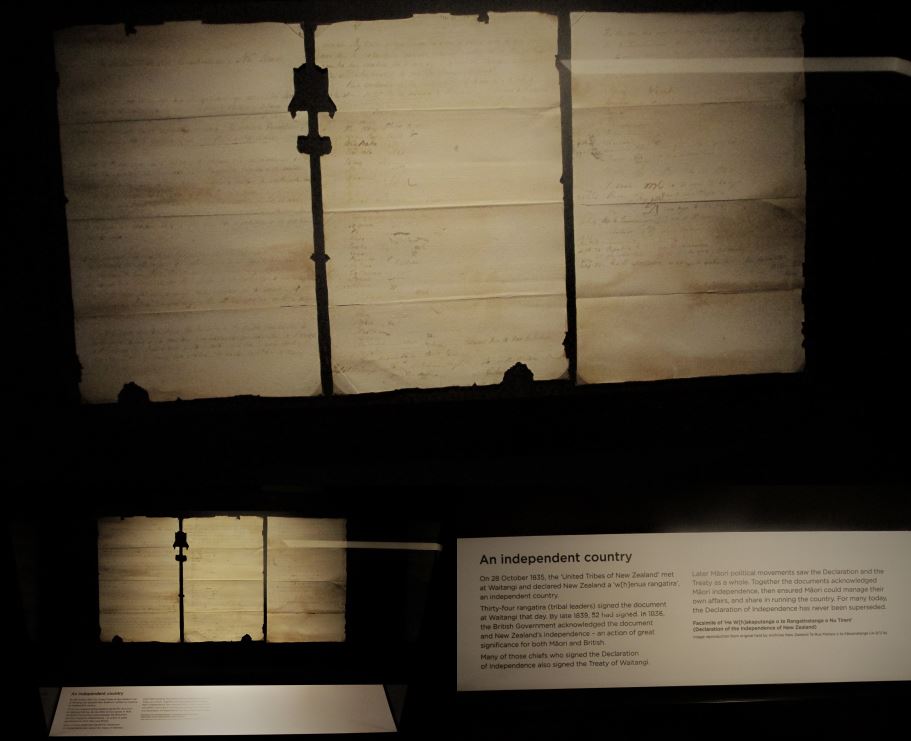

The Treaty Theatre Track began in June 1831, when James Busby outlined a policy he published in England, titled “Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand”, in which he wrote his dream job description as future British Resident with the power to make treaties with Māori. This Treaty Theatre Track advanced on October 5th 1831 with a letter signed by 13 rangatira asking King William IV for his protection. The ‘apparent’ joint British Resident-rangatira initiative for a National Flag for Shipping in 1834, his subsequent goading of Chief Rete, by interfering with the rangatira’s hapū’s logging trade, which led to the precedent-setting punishment that was New Zealand’s first British-inflicted land confiscation. This track to the treaty was advanced with the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand’, creating the edifice of an ‘independent state’. More Treaty track was laid was by Captain Hobson’s Factory System plan of 1837 which proposed a treaty for settlements. All of which culminated in the 1840 Te Tiriti o Waitangi, accompanied by its evil English language non-identical twin. The Treaty Signing Rituals served to defuse Māori resistance by tricking the Treaty Chiefs and Chieftainesses that they would retain their sovereign authority and power, while saving face for the British Parliament.

Treaty Theatre Track – From Busby’s Dream Job to Te Tiriti o 1840

In Beyond the Imperial Frontier: The Contest for Colonial New Zealand, the historian Vincent O’Malley stated, “Busby’s role as an agent of socio-cultural and political change among the northern tribes” had escaped the scrutiny that his machinations deserved. In the chapter “Manufacturing Chiefly Consent? James Busby and the Role of Rangatira in the Early Colonial Era”, O’Malley wrote:

“from the outset Busby had set about challenging existing northern leadership and governance structures in his efforts to manufacture a more centralised form of government, open to his ready manipulation on behalf of the British Crown.”xii

Tellingly, in a letter to his brother, Alexander, James Busby explained he intended to gain “almost entire authority over the Northern part of the island” by developing ties with rangatira – as O’Malley recounted.

Busby was likely advised by the Protestant missionaries of the Church Missionary Society that his objective to construct a Confederacy would only succeed if the chiefs believed they were authors of such collective action – as Samuel D. Carpenter found his 2009 report – Te Wiremu, Te Puhipi, He Wakaputanga Me Te Tiriti Henry Williams, James Busby, A Declaration And The Treaty commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal.xiii Busby assumed Māori had never conceived the ‘idea of confederating for any national purpose’ and he believed the New Zealand to be territories of tribes whose independent-minded chiefs could be lured into forming the appearance of a national government. In the field-study, Ngāpuhi Speaks, commissioned by Kuia and Kaumātua of Ngāpuhi asserted that the Northern Alliance chiefs had maintained a custom of gathering known as Te Wakaminenga that dated back to 1808, following the Ngāti Whātua victory over Ngāpuhi in the Northland battle of Moremonui at Maunganui Bluff, in 1807, at the beginning of the Musket Wars (1806-1845). Other issues arising from European contact were also discussed including international trade, land loss and challenges to tikanga. These Te Wakaminenga gatherings, which are referenced in Article One of the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835, did not usurp or over-ride hapū autonomy, and if there was consensus reached, the agreements were not binding – the ground-breaking Ngāpuhi Speaks study found.

In June 1831, James Busby outlined a policy published in England as a “Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand”, in which he wrote he a job description for a magistrate to live among Māori. Busby proposed to acquire a modest piece of land by contracting with the chiefs, be empowered to make treaties with rangatira, and set up a trade prohibition to exclude Europeans from such a district.xiv

Later in 1831, a letter of petition that was signed by 13 Māori chiefs by way of moko drawings, to King William IV asking for the King’s protection.xv The petition of October 5 1831, which was likely drafted by William Yate and Eruera Pare Hongi, has the clear hand of the Protestant missionary’s agenda. In September 1831, a rumour had spread that a French ship was coming to invade and evidently caused much alarm in the Bay of Islands, and several rangatira approached Reverend Henry Williams to seek protection from King William IV. A French corvette, La Favorite, arrived on October 3. The ‘Letter to King William IV’ emphasized the concern of Māori chiefs who had been manipulated into thinking ‘the Tribe of Marion’ (the French) is at hand, coming to take away our land.”xvi

In an oral and traditional history report, “He Rangi Mauroa Ao te Pö: Melodies Eternally New”, Associate Professor Manuka Henare, Dr Angela Middleton and Dr Adrienne Puckey, state that ‘Northern Māori oral tradition … does not record any alarmist tendency from among Māori about French intentions to take over the country’.xvii This 600-page report, which was received by the Waitangi Tribunal in 2013, frames this event as a continuation of ‘a dialogue of equals’, in this case between the thirteen signatories – Wharerahi and Rewa (Patukeha), Te Haara, Patuone and Waka Nene (Ngāti Hao), Kekeao, Titore, Tamoranga, Matangi, Ripe, Atuahaere, Moetara and Taunui – and King William IV.

However, this ‘dialogue of equals’ is bunk rhetoric that short-fuses critical thinking circuitry.

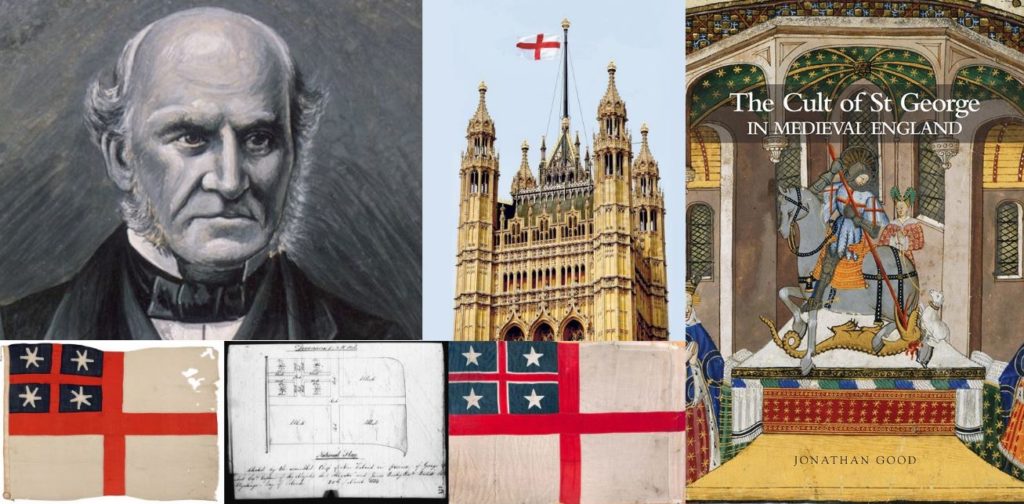

For one thing, William IV was the Sovereign Head of the dynastic English Order of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, which is England’s most prestigious and dynastic order. The Order of the Garter was founded in 1348, by King Edward the Third eleven years into the Hundred Years’ War fought over the Kingdom of France, and marked the decline of feudalism and the rise of nationalism. This Order of the Garter features the St George’s Cross, St George and the Dragon, and not surprisingly, given the Cult of St George, this legendary character is the patron of all knighthoods, according to Orders and Decorations, written by Václav Měřička. Indeed, new knights are often announced on St George’s Day. The Royal Monarch always becomes Sovereign Head of the Order upon ascension to the British Throne, which is located in the British House of Lords in Westminster City.

Meanwhile, in a letter dated November 10th 1831 that Busby wrote from London to his brother, N.Z.’s future British Resident proposed that he become “the authorised agent of the British Govt. in treating with the Native Chiefs [of New Zealand] for the Mutual protection of their own people and of the Europeans…”xviii In March 1832, Busby sent his Brief Memoir Relative to the Islands of New Zealand to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies of Britain, Lord Viscount Goderich, in which he hinted at French designs to takeover New Zealand and also of Russian interest in the archipelago. With the support of missionaries, and the favourable impressions he made on the Colonial Office, helped along with a tasty bribe of 40 bottles of wine produced at his vineyard in New South Wales, Busby was awarded the post as British Resident.xix Busby would be afforded the protection from Vice-Admiral of the Indian Squadron, Sir John Gore, who was ordered to deploy ships to visit principal harbours of New Zealand as frequently as possible.xx This protection was symbolic, since the ships would simply act a presence to remind all foreigners that the Royal Navy were the water police of a transmarine empire.

The response attributed to King William’s ‘mind’ came through a letter written by the high-ranking Secretary of State, Lord Viscount Goderich, who feigned to accept the rangatira communiqué of “friendship and alliance with Great Britain”. This letter carried the same date, 14 June 1832, as Goderich’s instructions for the British Residency appointment. Busby had suggested an audience with the King before his departure with the idea that it would elevate his esteem in the eyes of the chiefs. This idea was rebuffed. The logic of power suggests it would not suit the British Empire’s long-game to have the King so directly endorse their point-man for reeling in their big catch, with so little expended in fishing tackle and bait. It was this letter that Busby read on his arrival to a gathered audience of rangatira. After-all, rangatira had been led to believe that the encounters between chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato with King George III in 1820 signified the beginning of this ‘dialogue of equals’, rather than of two big fish taking the bait on two hooks of a very long line.

By the time of his arrival in Peiwhairangi, the Bay of Islands, on May 5th 1833, Busby was “resolved to bend the whole strength of my mind to effect this object” toward a Confederation of Chiefs.xxi After twelve days of badly behaved weather, Busby came ashore and read Goderich’s letter to an audience of 22 high ranking rangatira and more than 600 other Māori.

By exquisite serendipity, New Zealand’s first British official learned of the woes of Māori shipping before departing for New Zealand at Port Jackson, Sydney, from a ship owner Joseph Hickey Grose, who sought his help to get his impounded ship registered. Customs Authorities had a ship, the New Zealander, impounded in January 1833 for failure to be registered as a trading vessel and to fly a national flag.xxii This incident followed the November 1830 impounding of the Sir George Murray, with the Hokianga high chiefs and part-owners, Patuone and Te Taonui, on board.xxiii Because New Zealand had become a foreign territory to the Colony of New South Wales in 1823, and was not a recognized power, the indigenous-owned vessels could only be placed under the flag of a ‘friendly power’ once all the signatory chiefs’ marks were gathered and provided the ships were three-quarters crewed by ‘natives’ and then such ships could ply their wares under the Reciprocity Act.xxiv As the Waitangi Tribunal noted in its 2014 report, “He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti’:

“Busby astutely recognised that the issue provided an opportunity for him to draw the chiefs – who would probably never have contemplated ‘confederating for any national purpose’ – into working in concert. After his arrival in New Zealand, therefore, and a few days even before he was presented to Bay of Islands Maori, he outlined his plans to the Secretary of State of War and the Colonies, for the rangatira to come together and choose a national flag for New Zealand-built ships. He himself would undertake to certify the chiefs’ registration of the ships, but only if two-thirds of them agreed upon a flag design and petitioned King William to have it respected. Through this precedent he hoped the chiefs would ‘consent that they will henceforth act in a collective capacity in all future negotiations with me’, with the ensuing ‘confederation of chiefs’ providing the basis for an established Government’.”xxv

Evidently, Māori maritime commerce needed saving from the maw of the British Dragon of Maritime Traffic Infringements and it was lucky that British Resident James Busby just happened to hear of its peril while at Port Jackson. After this serendipitous encounter, Busby exploited the matter to get a national flag for Māori shipping as a cause célèbre mechanism to weld rangatira into a formalized collective federation of national purpose.

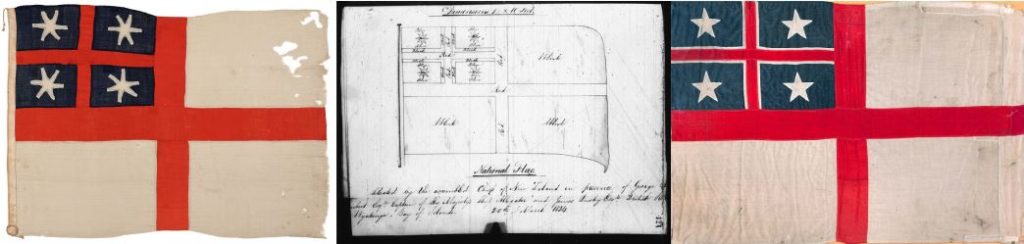

To this end, Busby cast himself as the heroic protagonist in the Cult of St George. The popular legend of St George valourizes his role as a soldier who saved a princess from the maw of a hungry dragon that won the customary right to eat sheep and children. The princess had been drawn in a ballot for sacrifice. With exquisite synchronicity, St George the Christian Knight just happened to be passing through the terrible scene. St George astutely saw an opportunity to expand the Church’s franchise and offered to save the princess on condition that the traumatized people convert to Christianity. In keeping with the legend of St George, he only does so by extracting a ‘pound of flesh’ from ‘the Natives’. In January 1834, Busby sent three flag designs, drawn by the Church Missionary Society Reverend Henry Williams, to Sydney to be produced as prototypes.

A hui was hastily called for March 20th 1834 to convene on the front-lawn at Busby’s house at Waitangi, with about 750 Māori in attendance.xxvi Busby’s design was to subvert Māori agency without the rangatira knowing the track he was leading them down. Embedded in Busby’s machinations were the gaining of submission of 26 selected principle chiefs, whom he lured to prostrate themselves to reach the exclusive cordoned off area to make their selections, by crawling under a British shipping rope inside a white make-shift ‘tent’ made of sails.xxvii Busby called the chiefs by name, whom included Waikato whom had met King George IV, along with Hone Heke, thereby creating a division “between the noblesse and the canaille (or common) of New Zealand … [causing] … no small discontent of the excluded”, as William Barrett Marshall recounted in his 1836 book, A Personal Narrative of Two Visits to New Zealand in His Majesty’s Ship, Alligator, A.D. 1834.

The Waitangi Tribunal reported the chiefs were baffled. An observer from a Royal Navy ship named after a species of tropical reptile, HMS Alligator, the Austrian Baron Karl von Huegel, noted that some chiefs queried the logic, because on the one hand, King William was said to be extending his friendship, while on the other hand they were being told the King’s men would seize their ships if they did not accede to a flag.xxviii Von Huegel recounted that the first three chiefs each chose a different flag, while the remaining chiefs, “did not care which flag was chosen”.xxix At this point, a servant of the missionaries, Eruera Pare, pressed each chief to make a choice and by this coercive method, he was able to tally up the score – according to Von Huegel’s account. The rangatira were indifferent to what was on offer. According to Busby’s own muddled speech, the rangatira were being pushed to make their preference while at the same time they were to confer with the chiefs in other parts of the country, “so that your decision would be the decision of the majority.”xxx

Twenty-eight votes were cast, with twelve votes were taken for the chosen flag, ten for the next choice and six for the third-place flag. Two chiefs abstained, “apparently apprehensive lest under this ceremony lay hid some sinister design on our parts”, as Marshall described.xxxi Marshall observed that “freedom of debate” was discouraged, since Busby invited no discussion, and he claimed a friend, called Chief Hau, evidently asked Marshall what flag was his preference. Hau subsequently voted for Marshall’s preferred flag design, with the St George’s Cross on it and apparently Hau canvassed other chiefs for their votes also. The new Te Kara flag, complete with the St George’s Cross motif, was raised on a poll next to a taller flagstaff flying the Union Jack, and a 21 gun salute was fired from the HMS Alligator followed the vote,xxxii the traditional pomp to make a sovereign and at this occasion, evidently to construct the illusion that the British were beginning to recognize the islands of New Zealand as a state.

Forebodingly for Māori, Busby invited about 50 European guests into his Residency for a meal, while his Māori guests were served outside with a ‘meal’ of ‘stir-about’, which was a thin paste of flour and water. Busby had deliberately under-catered to discourage Māori from turning up in large numbers and had also sought to place his indigenous guests in a lower status by excluding them from his table, and essentially serving them children’s glue as food, or what was fed to prisoners and the homeless in England. These insults demonstrate Busby’s machinations. The rangatira were tricked into participating in a precedent-setting Westminster Parliamentary-style of voting, to select a flag design out of a slim set of three choices.

While the Europeans were dining, rangatira performed fiery speeches outside. Chief Kiwikiwi spoke:

“How have we come into this situation of having to hoist a flag on our boats to ensure our own safety? It is through our own fault that we have to do it, if we had been more united among ourselves, if we had had no enmity of one horde against another, we would have been able to oppose their landing.”

With such exquisite serendipity, and by a narrow margin, enough of Busby’s selected chiefs just happened to choose the one with the St George’s cross on it, the very same cross on the Church Missionary Society flag and which appears on the flag of England. Busby gained their conversion to the cult of British Maritime Law, with their ascent to the adoption of a national flag, complete with the red St George’s Cross motif for abundant replication and a shipping register to entangle Māori shipping. This ‘winner’ only occurred after the chiefs were pressed to pick a preference. The firing of the 21 gun salute from HMS Alligator was theatrics and the dirty details of this episode in gaming Māori were excluded from Busby’s report.

The chiefs’ ‘choice’ gets more curious when it is learned that the Templar Knights adopted the Red Cross in 1145, and French troops used it during the Third Crusade or the Kings’ Crusade (1189-1192), that was co-sponsored by Phillip II of France and Richard I of England, and and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, while English troops used a White Cross in 1188 under Henry II. Philip II, William I and Count Phillip of Flanders met at Gisors in northeast France on January 13th 1188, to choose the three colours of crosses to be worn by their respective soldiers. The colour of three crosses signified which language to communicate with the troops.xxxiii George of Capadocia (modern day Turkey) or St. George, the Patron Saint of England, is venerated as a legendary champion of Truth and defender of the Christian religion.

With this chiefly ascent, Busby successfully riffed off Crusades history, by embedding the red version of St George’s Cross used by the French in the Kings’ Crusade, or the Third Crusade. Doubtless, these machinations entertained Busby greatly, particularly as this red cross was subsequently adopted by the English. Busby was, therefore, sticking it to the French, while at the same time signalling that stoking fears in Māori of France as the enemy – was actually an effective means of manipulation. In his role as ‘British Resident’, New Zealand’s first official was luring Māori chiefs to ascent to the jurisdiction of British Maritime Law, which meant Busby was formalizing the assertion of a Discovery Doctrine element known as Tribal Limited Sovereign and Commercial Rights.

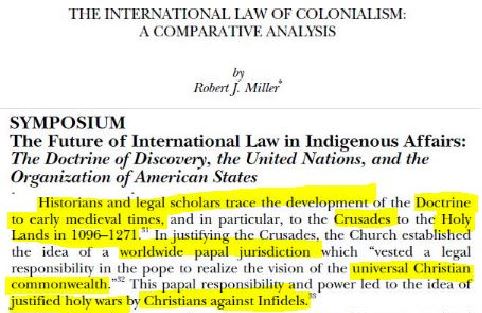

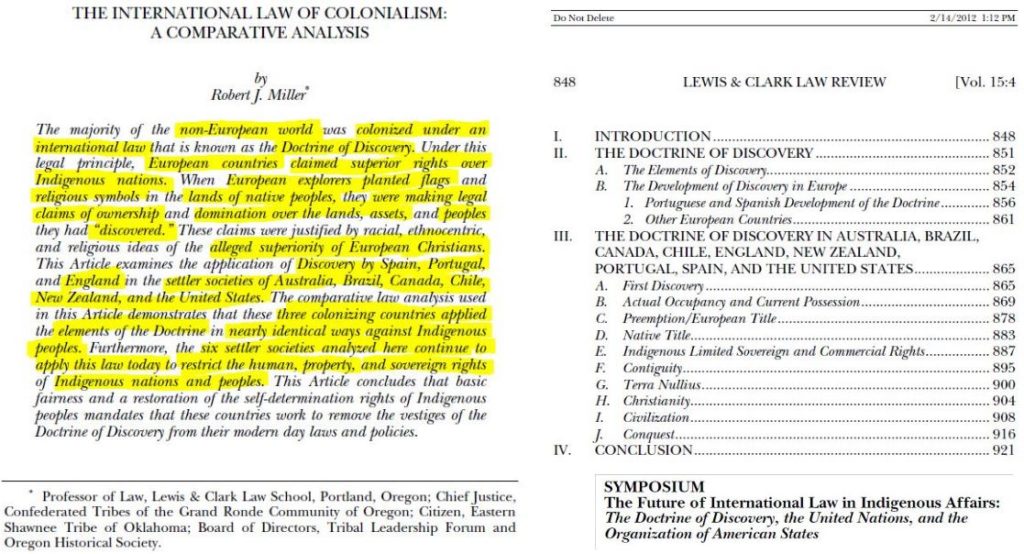

The Doctrine of Discovery was a secret piece of international law that emerged during the Crusades, which targetted the ‘Holy Lands’ between 1096 and 1271, when the Vatican Empire asserted a worldwide papal jurisdiction to justify Holy Wars fought by the Knights Hospitallers, the Knights Templars, and the Teutonic Knights. Muslim Saracens were cast as ‘Infidels’ and Christians could ‘legally’ reconquer their lands by divine mandate, which limited the property rights and self-government of non-Christian peoples, to serve the diabolical ambition to forge a universal Christian empire.xxxiv The Discovery Doctrine was further developed between European nations in the 15th Century, from whence they were forging maritime empires, and was designed to mitigate the chances of competing nations making expensive war with their technologically-even European competitors at the cost of much ‘blood and treasure’. The European Maritime Powers thought it would be easier to gain territory off ‘New World’ indigenous peoples, whom were cast as ‘savages’.

As indigenous law scholars Robert J. Miller and Jacinta Ruru stated in the West Virginia Law Review:

“When Europeans planted their flags and crosses in these ‘newly discovered’ lands they were not just thanking God for a safe voyage; they were instead undertaking the well-recognized procedures and rituals of Discovery designed to demonstrate their legal claim over the lands and peoples.”xxxv

Busby wrote to New South Wales Governor Burke:

“As this may be considered the first National Act of the New Zealand Chiefs it derives additional interest from that circumstance. I found it, as I had anticipated, a very happy occasion for treating with them, in a collective capacity, and I trust it will prove the first step towards the formation of a permanent confederation of the Chiefs, which may prove the basis of civilized Institutions in this Country.”xxxvi

The British Resident’s official correspondence was sanitized and at odds with his private words and his ‘public’ deeds.

Next, Busby antagonized a local chief, Rete, by bossing him and his hapū around about how to conduct their logging commerce. Rete was also annoyed that Busby had taken control of large tracts of land. Brazenly, Busby lobbied for Rete’s execution after the evidently insubordinate chief ransacked Busby’s storehouse,xxxvii and the British Resident copped a wood-splinter wound to his face when a musket shot hit the back-door frame, from where Busby had disturbed ‘the Natives’ one night in the midst of exacting a muru, or ritual compensation, in keeping with Māori customary law.xxxviii Because Rete’s New South Wales Governor Sir Richard Bourke permitted inflicting a retaliatory punishment. Rete’s huts were burnt and 130 acres of his village, Puketona, were confiscated and Busby renamed it Ingarani, the Māori transliteration for England.xxxix Busby later burnt down traditional fishing huts on the land he had bought when he found out that Rete and his friends had been using them. Busby has ‘allowed’ continued use of the huts by Māori, but set fire to them without notice and this action strained relations.

The incontrovertible fact is that Busby acted as an agent provocateur seeking to antagonize Chief Rete, having gained chiefly recognition of British Maritime Law. Busby’s provocation occurred after he had conned chiefs to vote for a flag of national shipping and therefore, volunteer their submission to British Maritime Law, and join in the system of international law.

Having successfully inflicted the first land confiscation with the participation of a dozen rangatira, three quarters of whom were bribed with presents, Busby then deployed his defining confidence trick: gaining chiefly participation in signing the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’, or He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene.

Busby stoked fears that Māori would be enslaved on the basis of a letter sent to him by a delusional Frenchman, Charles de Thierry, who claimed to declare sovereignty. Busby’s modus operandi was to turn any threat, real or perceived, into an opportunity and was part of the British strategy to game Māori.

Indeed, the origin of this ‘Declaration of Independence’ can be traced back to the ‘Letter to King William IV of October 5 1831’, which had been triggered amid widespread rumours of a French ship coming to take lands. Following the first signings of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ – 33 in all on October 28th – Busby eventually gained a full deck of cards worth of 52 chiefly marks and signatures over a four-year period, including chief Te Wherowhero.xl

In regard to whether the 1835 Declaration was Busby’s initiative, or that of Ngāpuhi rangatira, Ngāpuhi kaumātua Erima Henare challenges the credit that Pākehā historians bestow on Busby. In the Ngāpuhi Speaks report, it was conveyed that E. Henare pointed out that proof of Ngāpuhi agency in He Whakaputanga is the fact that when the iwi gathered at Busby’s residence at Waitangi in 1835 they fed themselves, while five years later, the missionaries stumped up for the food. Granted, there was clearly far more rangatira agency in the discussion that resulted in the composition of the final texts for the 1835 Declaration, than with the both versions of the Treaty, which were composed entirely by Pākehā. However, it is ultimately a fallacy of evidence to suggest that who laid on the kai for the home crew is proof of who had control of the foreign ship’s rudder carrying the dispatches, with the ‘all-important’ English versions of any letters, declarations or treaties carrying the marks of rangatira, as well as the Māori language versions. Particularly, as Busby had deliberately under-catered for the festivities following the vote for the Te Kara and creation of a shipping register on March 20th 1834, meaning he did not want to ever have to cater for Māori because he saw himself as above ‘the natives’. And because he was, in effect, conjuring more tracks and sleepers that would eventually culminate in an improvised low-speed Waitangi Treaty track section, or siding, where Māori would see the events moving past them on the faster track – creating the experience they had been caught in a ‘whirl-pool’ – like Prophet Papahurihia sensed after the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The significance of Busby’s machinations can be brought into sharper focus when it is recalled that the British Resident was shot at when he disturbed Chief Rete sacking his storehouse. In nearly all accounts of this incident, the reason why Rete was stealing Busby’s stores is omitted, thereby rendering Rete as a common thief. Even Ngāpuhi Speaks misses the full significance, despite this report recounting that Chief Rete was inflicting a muru since Busby was land speculating and threatening to stop the logging trade – as Pairama Tahere recounted.xli The writers miss the point about why exactly Busby’s first reaction on learning the identity of the culprit was to insist for Rete being executed. And omitted that the informant to Henry Williams was Ngāpuhi chief Hōne Heke Pōkai, of the same village, Puketona, whom would later surely have rued the day that he had ever performed the role of a ‘tell-take-tit’, since he was later, famously, driven to repeatedly cut down the flag-staff on the Maiki Hill above Kororāreka (Russell) in 1844 and 1845 to draw attention to the British takeover.

Ironically, Heke was no longer able to charge anchorage fees because authority had shifted to Crown’s officials and Hobson had shifted the capital from Kororāreka to Auckland, which caused significant economic decline. In other words, Heke’s rangatiratanga was being interfered with and decisions were being made without Māori. Heke had failed to care that Chief Reke had sensed his rangatiratanga was being breached by Busby and failed to see that Busby’s actions were about laying a Treaty Theatre Track. Because the muru that Reke was trying to inflict on Busby was construed as an act of theft, with the result that the Busby-Rete events cluster has been often been overlooked, the exquisite irony embedded in Heke’s flag-pole chopping has been also lost on earnest historians, Treaty scholars and Treaty workshop teachers.

In other words, New Zealand’s first British official wanted the life of the one man who was an immediate threat to his power, however limited, to be snuffed out. Because if the truth got out that he had exerted his bossiness over Rete’s business, the logic of Busby’s mindset would have been laid bare. This is why the reason for Rete’s muru, or ritual compensation, was rendered as a ‘theft’, and why – like so many crucial details in history – it was only carried in oral accounts by the ‘little people’ whom historians have a tendency to overlook. Even Anne Salmond misses this detail in her excellent, Tears of Rangi, despite her reading Ngāpuhi Speaks.

In his letters, Busby’s real attitude toward Māori rangatira is revealing. In a 16 June 1837 dispatch sent by Busby, the British Resident proposed the British Crown make a treaty with Māori and sought to persuade British to establish a protectorate government in New Zealand.xlii Busby referred to the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ to explain his logic:

“that the congress of chiefs … is competent to become a party to a treaty with a foreign power, and to avail itself of foreign assistance in reducing the country under its authority to order; and this principle once being admitted, all difficulty appears to me to vanish.”xliii

Moreover, he claimed that a treaty would be regarded by the chiefs as an acquisition of power rather than a surrender of power because:

“the New Zealand chief has neither rank or authority but what every person above the condition of a slave, and indeed the most of them, may despise or resist with impunity. It would, in this respect, be to the chiefs rather an acquisition than a surrender of power.”xliv

The Māori language version known as He Whakaputanga o 1835 bestowed authenticity to the English language version since this version was derived from the te reo Māori version, which was primarily drafted by Eruera Pare Hongi.

To the British Crown, the English language version of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ formalized New Zealand as an independent state controlled by a confederacy of chiefs. It was recognized as such by the British Crown in 1836 and the British Parliament in 1838, but more accurately applied to the Northern parts of the North Island, as well as the Waikato and Hawke’s Bay. The British were able to construe that New Zealand was an ‘independent state’ – while, curiously, at the same time the entire islands of New Zealand became a protectorate of the British Crown. While family groups and tribes exercised independence, their capacity to defend themselves against the full force of a foreign power, whether French, English or American, over several years was questionable. To the rangatira that signed He Whakaputanga o 1835 (or ‘A Declaration of New Zealand’s Māori Sovereignty’), the paramount sovereign power and authority that they asserted was derived from the sustaining and nurturing whenua or land. Because the United Tribes sought an alliance with the King William IV in return for protection from foreign invaders as well as trade, New Zealand, in effect, became a protectorate of Great Britain.

Snapshot: The 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ was designed to lure Māori chiefs into a British Protectorate jurisdiction, and to forestall French missionary influence.

The key points and differences between the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835 and the English language ‘Declaration of Independence’ of 1835 version are as follows.

In Article One of He Whakaputanga o 1835, the chiefs claimed paramount sovereign power and authority, which was derived from the sustaining and nurturing wenua or land. This assertion to absolute authority meant that the rangatira exercised customary law and their responsibilities anchored in the well-being and mana in their hapū regions. The Northern Alliance chiefs had maintained a custom of gathering known as Te Wakaminenga that dated back to 1808, following the Ngāti Whātua victory over Ngāpuhi in the Northland battle of Moremonui at Maunganui Bluff, in 1807, at the beginning of the Musket Wars (1806-1845). Other issues arising from European contact were also discussed including international trade, land loss and challenges to tikanga. These Te Wakaminenga gatherings, which are referenced in Article One of the Māori language He Whakaputanga o 1835, did not usurp or over-ride hapū autonomy, and if there was consensus reached, the agreements were not binding. While in Article One of the English language version of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’, the rangatira assert a confederacy of Tribes that constitutes an ‘independent state’.

The Second Article of the 1835 He Whakaputanga states this hierarchy of authority, expressed as kingitanga, mana and Tino Rangatira are derived from the land and hapu, or extended whanau units. Therefore, the authority of the paramount chiefs is grounded in wenua, or land and whakapapa or genealogy. The chiefs declared that they were responsible for framing laws and only persons appointed by them would be authorized to set down laws consistent with the Confederation of New Zealand’s meetings, such that a governor could not make laws in conflict with the rangatira laws. In the English language version, Article Two render “all sovereign power and authority” to its hierarchical effects of mana to exert control, whereas in the Māori language version, mana’s source is derived from the land.

In Article Three, the paramount chiefs resolve to meet each year in the autumn at harvest time, under the auspices of Te Wakaminenga gatherings. The intent of these annual Runanga was to dispense justice, ensure peace and confront wrongdoing and lawlessness and facilitate fair trade in commerce. Article Three also called upon iwi and hapū in other areas to join Te Wakaminenga and quit inter-tribal warfare, which reinforced the northern rangatira of Ngāpuhi declaring that the ‘land [was] in a state of peace’.

Article Four of He Whakaputanga emphasized an extension of friendship and alliance with the British monarch and Britain, which had its roots with chiefs Hongi and Waikato visiting England and King George IV on November 13th 1820.The rangatira express appreciation for the King’s recognition of their shipping flag and then promise to extend friendship and care toward British settlers and traders. The Tribal Confederacy entreated to the King of England to be the Protector from all attempts upon their mana and sovereignty, while in the English version, mana and sovereignty was rendered as independence. In seeking the King to act as ‘matua’, rangatira were asking the King to be a parent to his own British family! While in the English version, this parent or protector role was rendered to frame the independent state as a candidate for protectorate status of British Empire. In his review for the Waitangi Tribunal, Carpenter believed, this rendering in English as “protectorate language was a prominent code for British control at the time.”xlv

In the drafting of this Declaration, the crucial differences in stating chiefly sovereignty belies Busby’s machinations to construct the edifice of national autonomy for later de-construction. In the English language version, chiefly sovereignty is construed as a confederacy comprising a small number of chiefs whom essentially are placed – unwittingly – in a position to over-reach their authority claiming an independent state, with a binding hierarchical power structure that sought protectorate status within the orbit of the British Empire. Whereas, in the Māori language version, He Whakaputanga o 1835, hapū autonomy remained intact since chiefly authority was anchored in the well-being and mana in their hapū regions.

The crucial differences between the drafts of the Māori language and English language versions of the 1840 Waitangi Treaty is not simply because Busby recruited the help of Eruera Pare Hongi, to draft the Māori language version of 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’. In other words, in both the English and Māori language versions. The real reason is because the British game had been to erect the edifice of an independent sovereign state for its deconstruction at a later date.

To the British Crown, the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ and its Māori language version known as He Whakaputanga o 1835 – formalized New Zealand as an independent state supposedly controlled by a confederacy of chiefs. It was recognized as such by the British Crown in 1836 and the British Parliament in 1838, but more accurately applied to the Northern parts of the North Island, as well as the Waikato and Hawke’s Bay. To the rangatira that signed He Whakaputanga o 1835 (or ‘A Declaration of New Zealand’s Māori Sovereignty’), the paramount sovereign power and authority that they asserted was derived from the sustaining and nurturing whenua or land. Because the United Tribes sought an alliance with the King William IV in return for protection from foreign invaders as well as trade, New Zealand, in effect, became a protectorate of Great Britain.

Crucially, the one account that survives is Busby’s report – which is rather telling since the Te Kara national flag of shipping had some ‘unhelpful’, independent accounts that contradicted Busby’s propaganda. This is despite Reverend Henry Williams, a prolific diarist, and CMS printer James Clendon being present.xlvi This sparseness in accounts was to be repeated when the Treaty Theatre Track advanced to its historic production at Waitangi in 1840, with Captain Hobson as director.

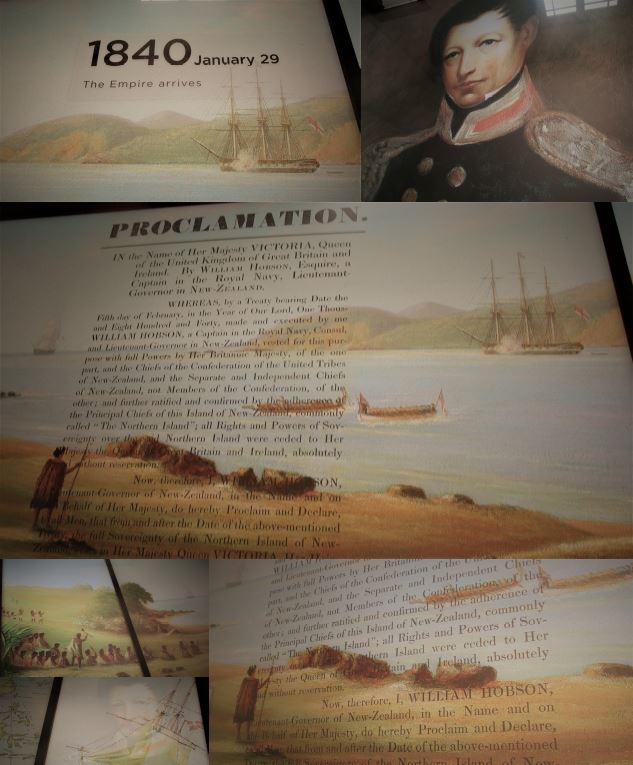

Like James Busby, Royal Navy Captain William Hobson was volte-faced in his dealings with Māori. Behind the friendly mask, was a scheming face and an ambitious egotistical mind. Captain Hobson first came to New Zealand in 1837, when he commanded the frigate, HMS Rattlesnake, to answer Busby’s dispatch to Sydney for help to quell fighting between two warring chiefs Pomare II and Titore. While briefly in New Zealand for between May and July, he visited other parts of the North Island.

The Royal Naval Captain had envisaged a ‘factories scheme’ for New Zealand that described a system of naval-protected trading posts owned by the British Crown, following a treaty. Captain Hobson’s 1837 plan envisaged the factory enclaves would be controlled by a British Governor, whom would have authority over Pākehā and Māori. In effect, this scheme meant the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Normanby, and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Bro. Palmerston, well-knew that Captain Hobson’s Factory Scheme was based upon the factory trading system used by the British East India Company. That factory trading system had been copied from the Portuguese to gain a foothold in India in 1668, first on the Island of Bombay, its port and its harbour. Governor Bourke wrote to the Colonial Office conveying that Hobson’s proposal was premised on ‘Māori’ cheerfully conceding to the factory plan on terms of mutual interest. However, Hobson was evidently less confident than Busby that a treaty would work, because he felt Maori had no form of government and any hui with chiefs claiming to be the heads of the United Tribes would likely result in bloodshed.xlvii

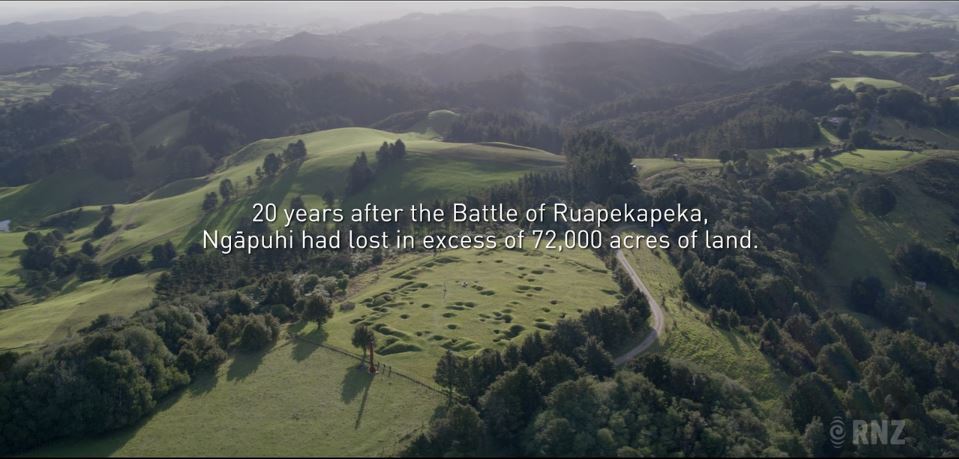

Thus, by sending no ordinary Royal Naval Captain to treat with the ‘Native Chiefs’ for their willing and conscious cession of sovereignty and informed consent to grant monopoly rights to extinguish native titles, Lords Normanby and Lord Bro. Palmerston made conscious decisions to sign-off on the trickery of gaining the appearance of paper sovereignty in 1840. That trickery was designed to eventually lead to structural entrapment – to justify a war of sovereignty. That structural entrapment would take the form of provoking Māori into reacting to incursions on their sovereignty, lands and customs, and would be the catalyst for the Northern War of 1845-46xlviii and the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-1872.xlix

All the European Maritime Powers, and the United States, constructed treaties with indigenous peoples in the formation of their imperial colonies, as Matthew Wright found in Waitangi: A Living Treaty.l These treaties were drafted at the conclusion of ‘little wars’, to establish commerce, and territories. However, Wright states that the 1840 Waitangi Treaty was the only one that the British used to gain full sovereignty by paper with an indigenous people. Because this innovation contained the trick of language translation deceptions, I argue, it could only work once because if it were repeated the cover-story of a hastily-drafted treaty in a far-flung location amid pressure of immigrant-laden ships arriving, land speculating syndicates swindling ‘Māori’, and the perennial French bogeyman showing up – would have long ago collapsed.

Snapshot: The Treaty Theatre pivoted upon a fulcrum of deceptive translation differences in the 1840 Waitangi Treaty texts that hid the deceptive power crime to win native signatures and paper sovereignty.

In 1840, the 39 Māori signers of English language version of the Waitangi Treaty and the 473 Māori signers of Māori language version, Te Tiriti o Waitangi – intended that their paramount authority would remain intact. In the 217-word long sentence that comprises the Preamble of the English version, Queen Victoria was alleged to have extended “Her Royal favour” to invite the Aborignees to cede sovereign authority to her, signalled the formation of Civil Government and justified this move to avert evil consequences of unregulated emigration. This rambling Preamble stated Her Majesty was “anxious to protect … [the] just Rights and Property” of the “Natives Chiefs and Tribes of New Zealand”.

Crucially, in the te reo version of the Preamble, “just Rights and Property” are rendered as “o ratau rangatitiratanga, me to ratau wenua”, which meant “their chieftainship and their land”. The bearing of this difference is significant because “Civil Government” and “sovereign authority” were translated by Rev. Henry Williams into Māori as “kawanatanga”, or governance/governorship. Also, Rev. Henry Williams translated “functionary” as “kai wakarite” which meant an administrator, mediator, negotiator or adjudicator, meaning Hobson’s role would have been understood by Māori as an official appointed by the Queen to make decisions sitting with or below rangatira, not above.

In Article One of the Māori language Te Titiri o Waitangi o 1840, the chiefs conferred the right of governorship, meaning authority was granted to the Queen to appoint a Governor to rule over Pākehā only. Meanwhile, in the English text, the chiefs signed away, or ceded, complete sovereignty over their territories. Rev. Henry Williams achieved this sleight of hand by rendering Kawanatanga or governorship to mean sovereignty.li The effect was that Kawanatanga was essentially construed to mean that Māori ceded sovereignty over New Zealand forever to the Queen of England!lii

Māori chiefs thought they retained their chieftainship, or independent authority, with the crucial term – tino rangatiratanga – in Article Two of the Māori language version. Both mana and tino rangatiratanga were regarded as paramount, spiritually sanctioned, inalienable power, as Emily Blincoe noted in her law paper, “The Myth of Cession: Public Law Textbooks and The Treaty of Waitangi”, that endorsed the Waitangi Tribunal’s October 2014 report, The Declaration and the Treaty.liii

In Article Two of both texts, Queen Victoria upheld the chieftainship over lands, village estates and treasures, while in the Māori language version the British Monarch gained the right to appoint an agent to barter or trade in land. However, the Second Article’s English text conferred the Queen of England the right of pre-emption, which was said to mean granting the exclusive right to purchase Māori lands at agreed prices. This exclusionary blackballing right of pre-emption was poorly understood by rangatira. This Discovery element of Preemption/European title was a powerful mechanism since it not only created a monopoly for the British Masonic Empire over private British enterprises. By appearing to gain this right, the British Crown constructed the capacity to extinguish Indian or Native Title created on First Discovery, that had the potential to last forever if indigenous nations never consented to sell to the European Maritime Power claiming the exclusive Preemption/European title right. It also foreclosed rival European Maritime Powers from gaining this right. This Pre-emption right constructed a Crown land-acquisition monopoly which would mean Māori would bare the burden of being coerced to sell lands at low prices in a new colonial economy where the profits from reselling land at inflated prices would supply money for public works and emigration. In effect, Māori land owners were force to ‘pay’ a kind of capital gains tax, as Keith C. Hooper and Kate Kearins in their study, “Substance but not form: capital taxation and public finance in New Zealand, 1840-1859” published in the Journal of Accounting History.liv

In the Māori text of Article Three, the Queen contracted to look after the Māori people and was afforded a kaitiaki role of guardian, in recognition of the governorship role accorded to her. In the English text, ‘the Natives of New Zealand’ were given “all the rights and privileges of British subjects”, as consideration for their chiefs signing away sovereignty. According to this version of the Third Article, the Māori signers fully understood the Treaty.

Rev. Henry Williams was well aware of the imperfections in the translation, and framed it in a way that would be agreeable to rangatira, whereby they would be led to believe a protectorate was being constructed and Queen Victoria recognized their independent authority or tino rangatiratanga. Dame Anne Salmond pointed out that Rev. Williams had not made clear the sovereignty being ceded to Queen Victoria, as he had in the Māori version of the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’. Salmond stated:

“If Williams had used the terms ‘ko te kingitanga ko te mana’ (as he did in He Wakapūtanga) to translate ‘sovereignty’ in Ture 1 [Article One] of te Tiriti, and asked the rangatira to cede these powers to the British Crown, it is almost certain that they would have been angry and affronted, and that the negotiations would have failed. Instead, he couched the cession to Queen Victoria as a tuku or release of ‘kāwanatanga”.lv

When vital consideration of the re-examined accounts of the circumstances that preceded the signings, the discussions rangatira had with Lieutenant-Governor Hobson, his agents and the missionaries, and the sly symbolic cession rituals of empire – are all laid bare – it is evident that rangatira were agreeing to the appointment of a governor to rule over unruly Pākehā, not Māori.lvi

Those Māori that signed were convinced by the sales-pitch of Hobson and Associates that they were signing a treaty with a great power to not only discipline troublesome Pākehā, but also to address land-swindling and protect Māori from foreign invaders in exchange for trade, limited immigration and co-development.

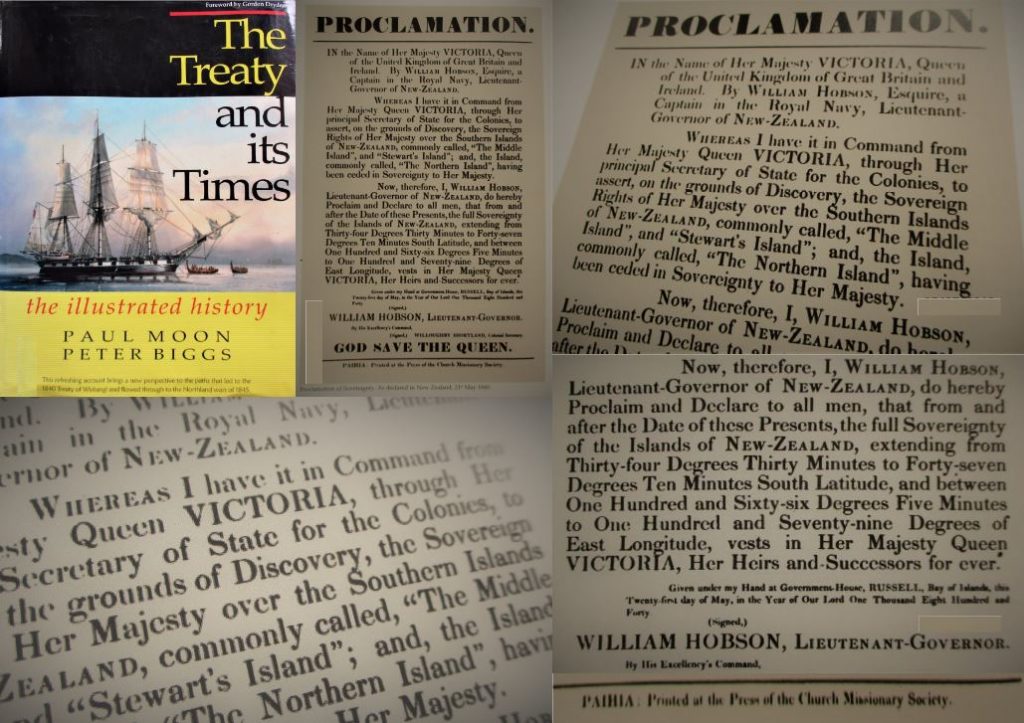

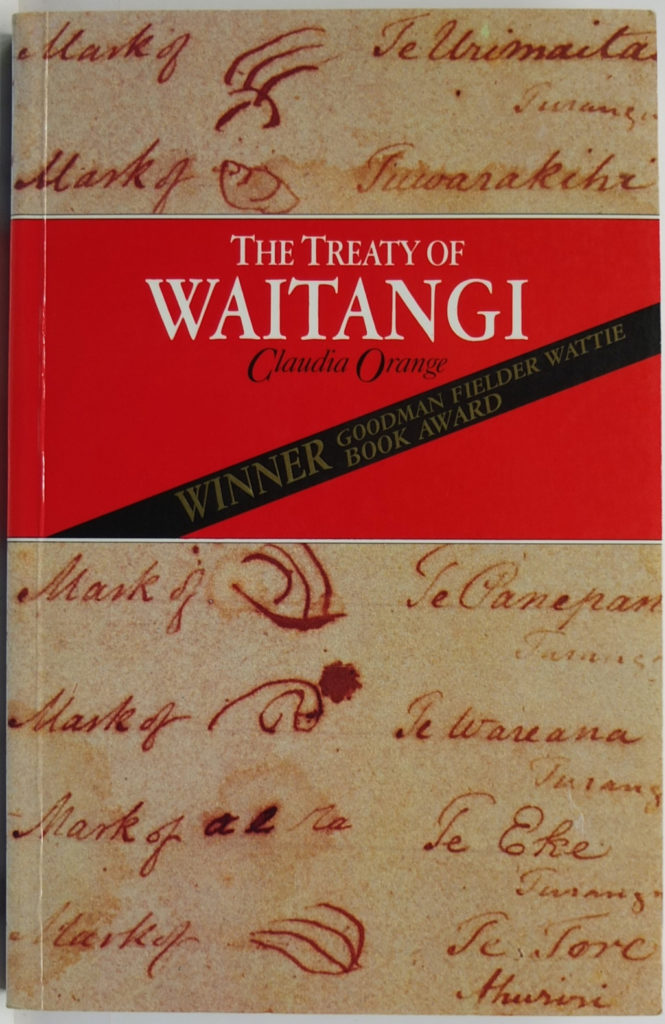

Furthermore, crucial assurances of Royal Navy Captain Hobson, his British Crown agents and the Protestant missionaries were given to rangatira, explicitly stating: (1) Queen Victoria would not dispossess Māori of their lands they did not willingly sell; (2) Māori would not become enslaved; and (3) rangatira would still retain their chiefly authority – as Dame Claudia Orange found in her Goodman Fielder Wattie prize-winning, imaginatively titled, 1987 book, The Treaty of Waitangi.lvii

Where Rev. Henry Williams’ hand clearly asserted Māori sovereign power and authority in the 1835 Declaration of Independence, that same hand wrote the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, with more ‘poisoned ink’. Moreover, the freshly retired official British Resident James Busby drafted the English language version of the 1840 Treaty. Busby had worked with his friend Rev. Henry Williams on the 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’, wherein they performed the same roles. Like Rev. Williams, Busy too had a past, one best described as a covert role was that of an Agent Provocateur to affect submission, exert authority and spread fear.

Prior to its deployment in the 1840 Waitangu Treaty, the pre—emption term as an exclusive land purchasing monopoly had only appeared in United States court cases in regard to the English colonies. In his 2011 book, Lords of the Land: Indigenous Property Rights and the Jurisprudence of Empire, Mark Hickford stated that New South Wales Governor George Gipps (1837-46) appeared to the be the “proximate source” of the pre-emption clause. Hickford said Gipps held an extensive collection of legal and historical tomes that he drew upon to exercise “the entitlement of imperial administrations to manage anglophone settlers and territories in alien locations”.lviii In law, pre-emption has another meaning, whereby a state acts pre-emptively in times of war, for instance, and takes land or resources before law is established. Conspicuously, the 1840 Treaty contained no provision for leasing Māori land, nor for Pākehā being conferred limited rights to use land, sea and other taonga or treasures that rangatira maintained control over.

Like all criminal plots, not everything went according to plan. Three ‘clanker moments’ that occurred during the 1840 Treaty hui at Waitangi required subterfuge by way of improvised theatre to avert the truth surfacing.

Discovery Doctrine & Treaty Clique’s Clanker Moments

Snapshot: A hidden Discovery Doctrine was deployed to gain paper sovereignty over New Zealand from Māori as part of a long game that would inevitably lead to war.

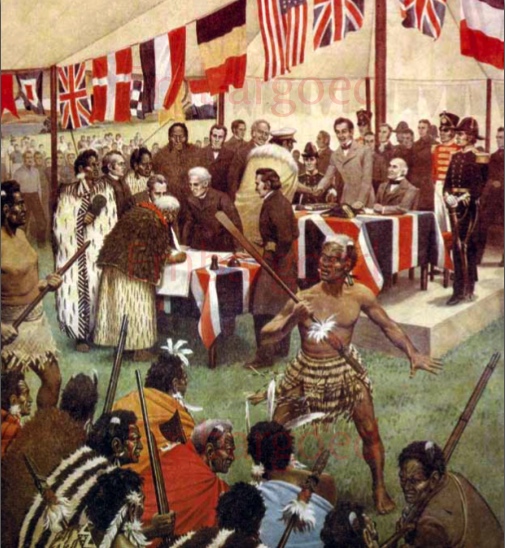

As the ‘stage director’ of what was really a ‘Waitangi Treaty Theatre Company’, Captain Hobson, leaned on the Protestant missionaries to help him persuade the rangatira about the benefits of a treaty with the British. Captain Hobson’s mission to persuade, or charm offensive, which occurred with unseemly haste, and along with the cast and props including the treaty sheets, quills and ink, made for New Zealand’s second theatre company – the first being Captain Cook’s voyages.

Scholar Professor Robert J. Miller, who published his findings in a book titled, Native America, Discovered and Conquered, identified ten elements of the Discovery Doctrine. The ten Doctrine of Discovery elements are: (1) First Discovery; (2) Actual Occupancy and Current Possession; (3) Preemption/European Title; (4) Indian Title; (5) Tribal Limited Sovereign and Commercial Rights; (6) Contiguity; (7) Terra nullius; (8) Christianity (9) Civilization; and (10) Conquest. Because the elements of this Discovery Doctrine are present in the circumstances, texts and intent of the 1840 Waitangi Treaty, as well as the earlier 1835 ‘Declaration of Independence’ – and therefore the Declaration’s hidden bearing of steering Māori toward an eventual loss of substantive sovereignty – these Discovery elements are identified as they surface.

The 1840 Waitangi Treaty was a Discovery Doctrine event brazenly designed as a deceptive power crime to win native signatures and paper sovereignty through the construction of a copy of reality. Once this copy of reality was embarked upon, conspiring players performed a theatre of contrived ignorance, including those who did not necessarily agree with the deception at Waitangi.

“Ostriches … are not merely careless birds.”

To this eventual end, the Treaty Cliqué at the scene of the 1840 Waitangi parchment crime included: Royal Navy Captain William Hobson, who convened a conclave of Protestant Missionaries aboard the ship, Herald; the primary drafter of the English text, British Resident James Busby; and the primary translator of the text into Māori, Church of England Reverend Henry Williams. This Cliqué also included: Captain Hobson’s Chief Clerk, James Freeman; Surveyor-General Felton Mathew; the CMS Missionaries, Richard Taylor, William Colenso, Charles Baker and George Clarke, and French Catholic Bishop, Jean Baptiste Pompallier. Remotely, the Treaty Cliqué included: Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Normanby; Governor of New South Wales George Gipps, and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Bro. Palmerston, the world’s High Priest of British Freemasonry.

Clanker Moments at Waitangi

The three ‘clanker moments’ that occurred during the 1840 Treaty hui at Waitangi required subterfuge by way of improvised theatre to avoid the entire fiction of the travelling production careening into a ravine of revelations. The risk of their ‘unveiling’ hinted at the Discovery Doctrine elements.

The first clanker moment came when Chief Te Kemara of Ngāti Rāhiri hapū – whom were hosting the hui since the meeting was technically and ironically on their land, but exclusively claimed by Busby – complained that the Anglican missionary Williams family had swindled him out of his land. The second clanker occurred when French Catholic Mission, Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier, interjected to ask Royal Navy Captain William Hobson – who was appointed British Consul to gain paper sovereignty – if there would be tolerance for diverse religious teachings under the treaty. A clanker moment of a third kind happened as Chief Hōne Heke Pōkai got up to sign, when Church Missionary Society (CMS) printer William Colenso asked Captain Hobson if the “Native chiefs” understood the treaty. Each of these clankers could have derailed what was, in effect, a track-laying vehicle for the British Masonic Empire to forge a colony out of what had been construed in 1835 as an independent Māori state comprised of numerous hapū and iwi.

That track-laying vehicle was the Discovery Doctrine.

If there had been defections by participants within the Treaty Cliqué during these clanker moments, the elements of the Discovery Doctrine would been exposed and its use as a track-laying vehicle ruined, without the chiefs needing to know about the doctrine itself. If a full-blown mutiny at Waitangi had revealed essential facts of context, it is likely that a walk out by the chiefs would have ensued, word would have spread. The likelihood that Captain Hobson’s, James Busby’s and Reverend Henry Williams’s heads being skewered on sticks by sunset might have prompted Treaty Cliqué’s surveyor Matthew Fenton to switch allegiances, and offer his artistic skills skilled to sketch and paint their demise for posterity to save his own skin.

The contextual facts of these clanker moments remained unspoken at Waitangi and therefore they remained at-large for historians to piece together later. Until now, however, the three clanker moments have not been identified as such, and therefore the task to summarize them and their significance has fallen upon The Snoopman nearly 180 years later.

When Chief Te Kemara supplied the first clanker aimed primarily at Rev. Henry Williams for swindling him of land in 1834, at a time when Māori had little understanding of private land tenure, the CMS Anglican missionary made inaudible and incomplete translations of Chief Te Kemara complaints and similarly those of Ngāi Tawake rangatira Rewa. Rev. Williams, who possessed 11,000 acres, defensively insinuated he was generous by paying a sum equal to the value of twice the acreage, which was still a pittance – since it would be lost forever. The Anglican missionary justified his large land holding as a means to provide for his children, since the Church Missionary Society had done little to provide cash. Slyly, Rev. Henry Williams, as the most senior Church Missionary Society clergyman, was masking his role in implementing an element of the Discovery Doctrine, Actual occupancy and current possession. A European Title could only be produced from First Discovery if the European country occupied and possessed their newly found lands. Fort building and settlements had to occur within a reasonable period, to complete the annexed title. Rev. Williams also complained he and the other missionaries had done so much for ‘the natives’ to lay the groundwork of civilization that his land holdings were justified reward.

Here, Rev. Williams’s attitude, in effect, belied an activation of the Discovery Doctrine element of Christianity and its conception of Civilization. As Discovery Doctrine scholar Professor Robert Miller states, “[u]nder Discovery, non-Christian peoples were not deemed to have the same rights to land, sovereignty, and self-determination as Christians.” Discovery’s Civilization element deemed that settlements were supposed to be surrounded by pastoral farming and crops. This Civilization element, along with the others, was highly subjective, and therefore meant the Crown would not accommodate or treat Māori land use and tenure on a par with European legal systems. In this way, the first clanker hit the Substantive Sovereignty Cog, which could only spin at full torque when the Māori communal economy was destroyed by land confiscations in war and peace, by swindle in purchases and promises, and by stealth in legislation, cases and myriad legal mechanisms cooked up by Pākehā ‘kitchen cabinets’.

The interjection of the French Catholic Missionary, Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier to ask if all religious creeds would have a place, provided a glimpse of the dark history between the British, French, American and Vatican Empires represented at Waitangi in February 1840. With this second clanker, Bishop Pompallier could have derailed the criminal proceedings to annex New Zealand by stealth, had he been open with the Māori about the rivalrous multi-century antagonisms between Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry, French Templar Freemasonry and the Vatican’s militant brotherhood of Jesuits. Māori in 1840 knew nothing of the rivalry between English Sionist Rosicrucian Freemasonry and French Jacobite Templar Freemasonry that had underpinned the epic warring between Britain and France. Yet, they were supposed to view British as a force for the light, and French as a force of darkness. As such, Māori in 1840 did not know that there were two British Empires, one Christian comprised of missionaries exerting ‘soft power’. The other, a hidden British Masonic Empire hell-bent on world domination that competed with Templar Freemasonry, whom had skillfully wrested control of America from the British Masonic Empire in the American Revolution and consolidated that win in the War of 1812.

Because Bishop Pompallier had a scheme of his own, he did not explain to Māori that the British and French had been warring for centuries. Pompallier wanted to beat the British and claim the South Island with a treaty for Catholic France, which would have meant the North Island would have become a British Masonic jurisdiction, while the South Island would have become a territory of the Vatican Empire. French Navy Captain Lavaud in the command of L’Aube, reported that Bishop Pompallier had said to him he could “press ahead and annex the South Island” and evidently added that “the English had done a great conjuring trick there”. lix

Yet, Pompallier’s claimed that prior to February 5th treaty hui, he had “enlightened the chiefs about what was involved for them and then left them to make their own decision, remaining politically neutral myself… Besides, I was quite sure that the request for signatures was only a pretext, the annexation was decided on …”. In other words, he had kept what he knew to be true from rangatira.

“Ostriches … are not merely careless birds.”

In response to Pompallier’s request, Hobson assured the Bishop that all creeds would be respected. Pompallier wanted something more than just spoken words. This was telling given that the chiefs relied more on spoken persuasion than on what was written down, and were unaware of the ruse in play regarding language translation differences – which Pompallier was conscious of.

Captain Hobson was astute and could see that this fourth article of the Treaty was needed to gain chief support of those affiliated with Pompallier. Ironically, the fourth article was, on paper at least, a counter to bigotry. Yet, it would become clear by the Northern War of 1845-46 and the New Zealand Masonic Revolutionary War of 1860-72, that the Crown was intolerant of Māori independence exerted through retention of lands.

Church Missionary Society (CMS) printer William Colenso could also have derailed the epic rort in play when he cautioned the missionaries that they had a duty to explain the treaty “in all its bearings to the Natives” so that the Treaty is “their own very act and deed” (rather than a dark work of criminal fiction). Colenso even foresaw the consequences when he said that Māori would have every right to confront the missionaries in the future for failing to make clear what the Treaty contained. Conspicuously, Captain Hobson made no further effort to explain to Māori assembled that the English version stated Māori would cede forever sovereignty over New Zealand to the British Monarch. Moreover, Rev. Henry Williams ‘failed’ – even after Colenso’s caution – to point out the deliberate differences between the two language versions of the Treaty to the chiefs assembled.

As Anne Salmond noted in Tears of Rangi, Henry Williams emerged as a “pivotal figure” in the Waitangi Tribunal hearings into the 1835 Declaration and the 1840 Treaty events. The battle-hardened naval lieutenant-turned missionary had fought in the Napoleonic Wars, which included the so-called ‘War of 1812’.lx These wars were actually part of British Freemasonry’s war against French Templar Freemasonry – as these conflicts become clear from reading English historian Nicholas Hagger’s epic study, The Secret History of the West, and Anthony Chaitkin’s, Treason in America.

The identification and location of these clanker moments in this deep historical context are pivotal to comprehending the machinations that underpinned the construction of the Treaty Theatre Track. The Treaty Theatre could only work if all hands, tongues and ‘sincere’ face-masks acted in unison with unseemly speed through the phases of scripting, ritualistic theatrical persuasion performances and the poste haste Waitangi Signing Tour Rituals – lest the imperial intrigue become obvious. Betwixt the spiraling momentum of deception in the unfolding events – that were embedded with weaponized speed – the Treaty Cliqué’s scheme almost went awry when three clankers moments emerged during the discussions at Waitangi in 1840. The narrative elements in the Crown’s bedtime fairy tale creation myth of how and why the New Zealand State became a British Colony in 1840 becomes sharper when by adding a ‘Masonic lens’ to view these clanker moments. A ‘Masonic lens’ clarifies the events, principle players, and the British Deep State’s machinations to forge a British Masonic jursidiction, in part to forestall their perennial rival, French Templar Freemasonry, whom as a secret Brotherhood succeeded in winning the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) to establish the United States as a Masonic Templar State.

With this sharpened view, works such as Mike King’s Waitangi Treaty documentary series – Lost in Translation – could be reworked, especially the first episode which was evidently dedicated to Mike King’s ego. The film-tape and air-time expended on the comedian’s boring awakening story after recovering from a heart attack, can now be used to explore the clanker moments as being consistent with the uneasiness, defections and staged challenges to the in-built fraud that the Treaty Cliqué all knew to be true.